Magnolia virginiana

Common name: sweetbay,[1] southern sweet bay, northern sweet bay[2]

| Magnolia virginiana | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John B | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Magnoliales |

| Family: | Magnoliaceae |

| Genus: | Magnolia |

| Species: | M. virginiana |

| Binomial name | |

| Magnolia virginiana L. | |

| |

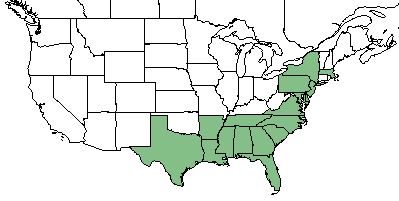

| Natural range of Magnolia virginiana from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: Magnolia virginiana ssp. australis (Sargent) A.E. Murray; Magnolia virginiana ssp. virginiana[2]

Varieties: Magnolia virginiana Linnaeus var. australis Sargent; Magnolia virginiana Linnaeus var. virginiana[2]

Description

M. virginiana is a perennial shrub/tree of the Magnoliaceae family native to North America.[1]

Distribution

M. virginiana var. australis ranges from southern North Carolina to southern Florida, then west to Texas. Rarely, it extends into adjacent interior provinces. There are disjunct populations in northwest Cuba. Magnolia virginiana var. virginiana has a more northern range, growing from southeast Massachusetts south to western North Carolina, southern South Carolina, and eastern Georgia[2] with disjunct populations in northwestern Virginia.[3]

Ecology

Habitat

M. virginiana proliferates in pocosins, bay forests, and swamps in the Coastal Plain, streamhead pocosins, swamps, and sandhill seeps in the Sandhills, bogs, and peaty swamps in the Piedmont and Mountains.[4] Specimens have been collected from shrub-tree bogs, wet hammocks, wet woodlands, pine woods, forest-adjacent roadsides, moist sloping plains, bottomland woodlands, cypress swamp-edges, sandy roadsides, swampy woods, slash pine flatwoods, floodplains, pine-palmetto flats, wiregrass bogs, wet cabbage-palm hammocks, and live oak hammocks.[5] M. virginiana does not respond to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.[6]

Magnolia virginiana is an indicator species for the Panhandle Seepage Savannas community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[7]

Phenology

M. virginiana has been observed flowers April through June and fruits from July through October.[8]

Fire ecology

M. virigniana is fire resistant but has no fire tolerance.[1]

Herbivory and toxicology

M. virginiana is highly palatable to browsing animals.[1] It has been observed to host the assassin bug Zelus longipes (family Reduviidae).[9]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

M. virginiana is listed as endangered by the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program and the New York Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Land and Forests, and as threatened by the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources and by the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation Natural Heritage Program.[1]

Cultural use

Magnolia tea from the roots, bark, and cones, as well as tincture from the leaves, was used by Native Americans to treat rheumatism, and tea from the branches was good for treating colds. The root bark was useful for treating malaria, and - when combined with brandy - lung diseases, dysentery, and fever. The tincture could also be used as a laxative and for gout.[10]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 USDA Plant Database https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=MAVI2

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "weakley" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Sorrie, B. A. and A. S. Weakley 2001. Coastal Plain valcular plant endemics: Phytogeographic patterns. Castanea 66: 50-82.

- ↑ Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: R.K. Godfrey, Loran C. Anderson, Gwynn Ramsey, Richard S. Mitchell, L.B. Trott, R. Kral, P. L. Redfearn, Lovett Williams, Andre Clewell, E.A. Hebb, N. Summerlin, Robert Lemaire, N.H. Chevalier, Sidney McDaniel, Gary Knight, Mark Garland, J.P. Gillespie, R.A> Norris, R. Komarek, Lisa Keppner, Cecil Slaughter, Morris Adams. States and counties: Florida (Liberty, Jefferson, Osceola, Leon, Madison, Jackson, Wakulla, Taylor, Gadsden, Polk, Volusia, Bradford, Walton, Union, Bay, Broward, Collier, Franklin, Bay, Orange, Calhoun, Washington, Holmes) Georgia (Thomas, Grady) Alabama (Houston)

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 24 MAY 2018

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- ↑ Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.