Ageratina altissima

| Ageratina altissima | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John R. Gwaltney, Southeastern Flora.com | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae ⁄ Compositae |

| Genus: | Ageratina |

| Species: | A. altissima |

| Binomial name | |

| Ageratina altissima (L.) King & H. Rob. | |

| |

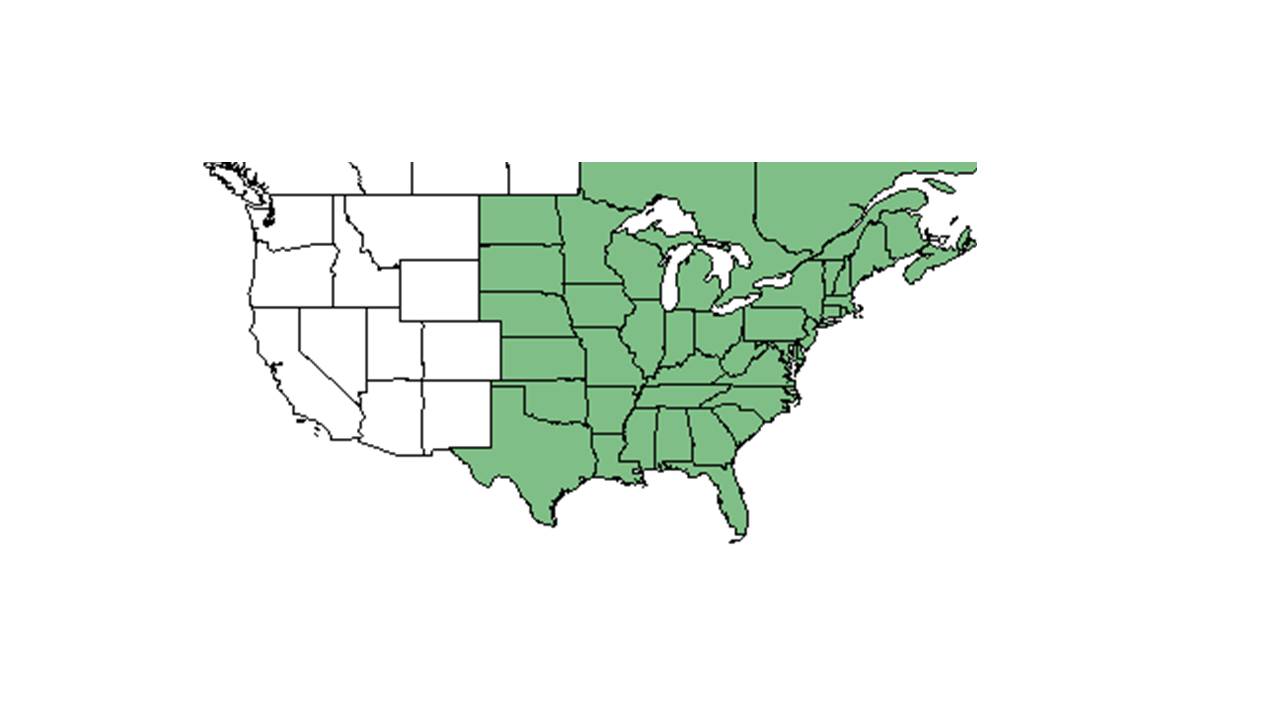

| Natural range of Ageratina altissima from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Snakeroot; White snakeroot

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Eupatorium rugosum Houttuyn; E. roanensis Small.[1]

Description

A description of Ageratina altissima is provided in The Flora of North America. It is a perennial.[2]

Distribution

It is common in north Florida. Found west to Texas and north to Canada.[2]

Ecology

Ageratina altissima competes by allelopathy. Aqueous extracts from roots and especially shoots decreases the rate of germination, percentage of germination, and size of germinated Lettuce and Radish seeds in Petri dishes as well as in pots of forest soil.[3]

Habitat

In the Coastal Plain, Ageratina altissima grows in shady to partially shady areas,[4] preferring wet or moist soils, including sandy alluvial soil, drying sandy loam, and wet loamy soil with limestone outcrops.[5]

The plant is common in the eastern deciduous forest herb layer.[3] This species also occupies scrubs, thickets, floodplain forests, and slope/bluff habitats.[4] It can also be found in disturbed areas like roadsides, old fields, clearings, and the margins of waterways.[5]

Associated species include beech, hickory, magnolia, sweetgum, pine, Taxodium, Nyssa, Acer, Fraxinus, Quercus, Eupatorium perfoliatum, and others.[4]

Phenology

In the Coastal Plain, Ageratina altissima flowers and fruits between late summer to fall,[6][3] with peak inflorescence in September, October, and November.[4][7]

Seed dispersal

A. altissima disseminates its mature seeds (achenes) by wind in fall and winter. Each plant can produce thousands of seeds at a time. [8]

Seed bank and germination

Ageratina altissima usually needs light to germinate. It exhibits a Type II response to stratification: Germination in the spring generally can occur at a lower temperature than germination in the fall as a result of dormancy loss in the winter. Thus, germination in the spring is more likely because of relatively higher temperatures and lower temperature requirements than in fall.[5]

Fire ecology

A. altissima resprouts following fire. It is most abundant after a late-season (early October) burn. [9]

Pollination and use by animals

Ageratina altissima has been observed with sweat bees from the family Halictidae such as Agapostemon sericeus and Augochlorella persimilis, as well as flies from the families Chloropidae and Calliphoridae.[10] Additionally, this species is known to host ladybugs such as Coccinella septempunctata (family Coccinellidae).[11] Otherwise, A. altissima is mostly avoided by many insects.[3] This species contains tremetol, a complex alcohol and glycoside that can cause a fatal disease known as staggers in cattle. The toxin is capable of being passed through milk and can cause fatalities in humans who consume infected milk.[12]

Diseases and parasites

Leaf miners and flea beetles may attack the foliage.[13]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Native Americans have reportedly used a decoction of the roots as a remedy for snake bites.[13]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Hall, David W. Illustrated Plants of Florida and the Coastal Plain: based on the collections of Leland and Lucy Baltzell. 1993. A Maupin House Book. Gainesville. 100. Print.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Corbett, B. F. and J. A. Morrison (2012). "The allelopathic potentials of the non-native invasive plant Microstegium vimineum and the native Ageratina altissima: two dominant species of the eastern forest herb layer." Northeastern Naturalist 19: 297-312.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Robert K. Godfrey, P. L. Redfearn, Jr., Richard S. Mitchell, Patricia Elliot, Robert L. Lazor, John B. Nelson, A. Gholson Jr., Angela M. Reid, and K. M. Robertson. States and Counties: Florida: Leon, Jefferson, Jackson, Gadsden, Liberty, and Calhoun. South Carolina: Greenville.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Walck, J. L., C. C. Baskin, et al. (1997). "Comparative achene germination requirements of the rockhouse endemic Ageratina luciae-brauniae and its widespread close relative A. altissima (Asteraceae)." American Midland Naturalist 137: 1-12.

- ↑ Wunderlin, Richard P. and Bruce F. Hansen. Guide to the Vascular Plants of Florida. Second edition. 2003. University Press of Florida: Gainesville/Tallahassee/Tampa/Boca Raton/Pensacola/Orlando/Miami/Jacksonville/Ft. Myers. 295. Print.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed:15 JAN 2015

- ↑ Lau, J. M. and D. L. Robinson (2010). "Phenotypic selection for seed dormancy in white snakeroot (Eupatorium rugosum)." Weed Biology & Management 10: 241-248.

- ↑ Pavlovic, N. B., S. A. Leicht-Young, et al. (2011). "Short-term effects of burn season on flowering phenology of savanna plants." Plant Ecology 212: 611-625.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [2]

- ↑ [[3]]Accessed:March 22, 2016

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 [[4]]Missouri Botanical Gardens. Accessed: March 22, 2016