Passiflora incarnata

Common name: Purple passionflower[1], Maypop[2]

| Passiflora incarnata | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John Gwaltney hosted at Southeastern Flora.com | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Violales |

| Family: | Passifloraceae |

| Genus: | Passiflora |

| Species: | P. incarnata |

| Binomial name | |

| Passiflora incarnata L. | |

| |

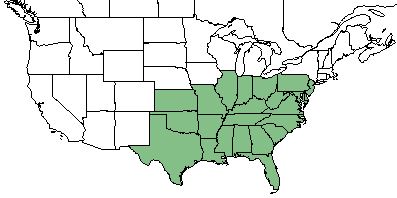

| Natural range of Passiflora incarnata from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: none.[3]

Varieties: none.[3]

Description

P. incarnata is a perennial forb/herb/vine of the Passifloraceae family native to North America.[1] It climbs with axillary, simple tendrils. Its leaves are alternate, simple, and stipulate. The flowers are actinomorphic, solitary, ar fascicled in the leaf axils. There are five sepals, five petals, and a conspicuous corona. There are 5 stamens, 3 styles, capitate stigmas, and a 3-locular ovary. The sepals are 25-35 mm long, green on the outer surface, white on the inner surface. The petals are 30-40 mm long, lavender, violet, or mauve. The berry is 40-70 mm long, while the corona is in 2-3 series, the longer being 15-30 mm long.[3][4]

This plant is a smooth vine with finely hairy stems climbing to a height of 10 to 30 feet. Its smooth or somewhat hairy leaves, 3 to 5 inches broad, consist of three oval or egg-shaped lobes with finely toothed margins. The flowers, which appear from May to July, are solitary and are characterized by a lavender and purple or pink and purple fringe 1 1/2 to 2 inches broad. The plant produces smooth, yellow, many-seeded, edible fruit almost 2 inches long, called maypops.[5]

Distribution

P. incarnata ranges from southern New Jersey, Deleware, Maryland, southwestern Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Oklahoma, then south to southern Florida and southern Texas.[3]

Ecology

Habitat

P. incarnata proliferates in roadsides, fencerows, thickets, and fields.[2] Specimens have been collected from pine flatwoods, fields, roadside, live oak hammock, old field, sandysoils, fence row, open pasture, waste area, old brick wall, and shore of lake.[6]

Phenology

P. incarnata flowers from May through July.[3]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates.[7]

Fire ecology

Populations of Passiflora incarnata have been known to persist through repeated annual burning.[8]

Herbivory and toxicology

Passiflora incarnata has been observed to host brush-footed butterflies such as Agraulis vanillae (family Nymphalidae), sweat bees such as Lasioglossum pilosum (family Halictidae), and bees from the family Apidae such as Melissodes communis and Xylocopa virginica.[9]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

P. incarnata is listed as rare by the Indiana Department of Natural Resources Division of Nature Preserves, as threatened by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources Division of Natural Areas and Preserves, and as a weedy or invasive species by the University Press of Kentucky and the Southern Weed Science Society.[1]

Cultural use

Native Americans used the plant in poultices for treating bruises, injuries, burns, skin eruptions, and hemorrhoids. The juice could be used for sore eyes, and the root was thought to be an aphrodisiac.[10]

The vine is used for perfumes in Bermuda.[11]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 USDA Plant Database https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=PAIN6

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ Radford, A. E., Ahles, H. E., & Bell, C. R. (1968). Manual of the vascular flora of the Carolinas. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- ↑ Sievers, A. F. (1930). American medicinal plants of commercial importance. Washington, USDA.

- ↑ URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: D.L. Fichtner, P.L. Redfearn, Jean Wooten, O. Lakela, P.O. Schallert, Lovett Williams Jr., J.P. Gillespie, William Masters, S.W. Leonard, Gwynn Ramsey, Larry Stripling, R.K. Godfrey, Kurt Blum, Dave Breil, David Thompson, Nancy Caswell, Michael Cartrett, R.F. Doren, Kathy Craddock Burks, Gary Knight, Robert Kral, N.C. Henderson, R.F> Christensen, Samuel B. Jones, John Bruza, H.F.L. Rock, Norma Hammill, Roomie Wilson, William Gills, A.E. Radford, Lindheimer, Loran Anderson, Kevin Oakes, Chris Cooksey, Lise Keppner, William Platt, John Nelson, Robert Loftin, B.J., Wm. Damiano, E.C. Prichard, James Shelley, Jo Davidsmeyer, Shirley Wingfield. States and counties: Florida (Leon, Polk, Levy, Hillsborough, Seminole, Franklin, Orange, Madison, Dixie, Jackson, Jefferson, Calhoun, Wakulla, Washington, Volusia, Lake) Georgia (Towns, Thomas, Grady, Cobb, Calhoun, Mitchell) Tennessee (Davidson, Montgomery) Missouri (Christen, Bates) Mississippi (Pike, Forrest, Lincoln) Alabama (Geneva) Louisiana (Jefferson, Oachita) South Carolina (Richland, Bamberg) North Carolina (Martin) Texas (Comanche)

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- ↑ Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.

- ↑ Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.