Parthenocissus quinquefolia

| Parthenocissus quinquefolia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by James H. Miller & Ted Bodner, Southern Weed Science Society, Bugwood.org | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Rhamnales |

| Family: | Vitaceae |

| Genus: | Parthenocissus |

| Species: | P. quinquefolia |

| Binomial name | |

| Parthenocissus quinquefolia (L.) Planch. | |

| |

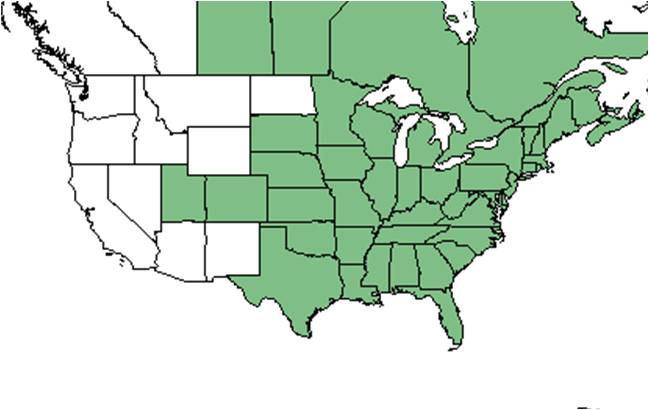

| Natural range of Parthenocissus quinquefolia from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Virginia creeper

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Parthenocissus hirsuta (Pursh) Graebner[1]

Varieties: none.[1]

Description

"High climbing vine with white pith and many tendrils with adhesive disks. Leaves palmately compound, petiolate; leaflets 3-7, usually 5, ovate, elliptic, or obovate, to 15 cm long and 8 cm wide, glabrous, usually pale beneath, occasionally pubescent, acuminate, coarsely serrate, usually above the middle of the blade, base cuneate or oblique, petiolulate. Inflorescence a panicle of cymes. Calyx flat, usually without lobes; petals 5, separate, yellowish-green, 2-3 mm long; disk small, adnate to ovary; stamens 5, filaments short; style ca. 0.5 mm long. Drupes black or dark blue, globose, 5-9 mm in diam.; seeds 1-3, lustrous brown, planoconvex, obovoid, 3.5-4 mm long."[2]

Distribution

The range is from Quebec and the Northeastern United States across to Minnesota, south to Texas, Florida, Cuba, Bermuda, and the Bahamas.[3]

Ecology

Habitat

P. quinquefolia has been found in pecan trees, mesic pine-oak-maple woodlands, swamp forest edges, and loamy sand areas.[4] It is also found in disturbed areas including wooden telephone poles, trees bordering cultivated fields, abandoned buildings, and abandoned highway bridges.[4] Associated species: Ligustrum and Celtis laevigata.[4]

Parthenocissus quinquefolia is an indicator species for the Calcareous Savannas community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[5] Parthenocissus quinquefolia grows along fences in ditches, disturbed areas, moist hammocks and woods, and frequently occurs in rocky areas.[6]

P. quinquefloia increased its presence in response to soil disturbance by heavy silvilculture in North Carolina longleaf pine sites. It has shown regrowth in reestablished native habitat that was disturbed by these practices.[7] It does not respond to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.[8]

Phenology

P. quinquefolia flowers from May through July and fruits from July through August.[1]Leaves turn orange and red shades. Leaves are lost in cold winter weather. Flowering occurs from January through August in South Florida and April through June to the North. Fruiting occurs from June to November in South Florida and June to September to the North.[9]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates.[10]

Fire ecology

Populations of Parthenocissus quinquefolia have been known to persist through repeated annual burning.[11]

Pollination and use by animals

Parthenocissus quinquefolia has been observed at the Archbold Biological Station to host bees such as Apis mellifera (family Apidae), plasterer bees such as Colletes nudus (family Colletidae), sweat bees from the Halictidae family such as Augochloropsis anonyma, and A. metallica, leafcutting bees from the Megachilidae family such as Coelioxys sayi, and Megachile mendica, spider wasps from the Pompilidae family such as Episyron conterminus posterus, and Tachypompilus f. ferrugineus, as well as wasps from the Vespidae family such as Mischocyttarus cubensis, Parancistrocerus fulvipes rufovestris, P. perennis anacardivora, Polistes bellicosus, Stenodynerus beameri, and Vespula squamosa.[12] Additionally, P. quinquefolia has been observed to host bees such as Aphis sp. (family Aphididae), treehoppers from the Membracidae family such as Telamona ampelopsidis and Smilia camelus, leafhoppers from the family Cicadellidae Erythroneura beameri, E. comes, E. elegans, and E. tricincta, sweat bees from the Halictidae family such as Lasioglossum cattellae, L. imitatum, and L. marinum, leafcutting bees from the family Megachilidae such as Coelioxys octodentata, C. sayi, Megachile mendica, and M. xylocopoides, and planthoppers such as Pelitropis rotulata (family Tropiduchidae).[13]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

Parthenocissus quinquefolia Photo by Karan A. Rawlins, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 694. Print.

- ↑ Hall D. 1986The Joy of Weeds-Florida Wildflowers Virginia Creeper Palmetto 6(1):12

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Florida State University Herbarium Database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Robert K. Godfrey, Holmes, R. Komarek, Karen MacClendon, and Travis MacClendon. States and counties: Florida: Calhoun, Jefferson, Madison, Wakulla, and Washington. Georgia: Grady.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Hall D. 1986 The Joy of Weeds-Florida's Wildflowers Virginia Creeper Palmetto 6(1):12

- ↑ Cohen, S., R. Braham, and F. Sanchez. (2004). Seed Bank Viability in Disturbed Longleaf Pine Sites. Restoration Ecology 12(4):503-515.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Hall D. 1986 The Joy of Weeds-Florida's Wildflowers Virginia Creeper Palmetto 6(1):12

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]