Serenoa repens

| Serenoa repens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida – Monocotyledons |

| Order: | Arecales |

| Family: | Arecaceae ⁄ Palmae |

| Genus: | Serenoa |

| Species: | S. repens |

| Binomial name | |

| Serenoa repens (W. Bartram) Small | |

| |

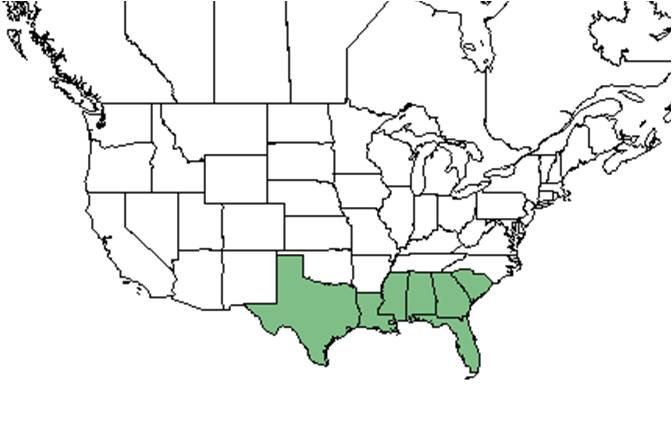

| Natural range of Serenoa repens from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Saw palmetto

Contents

Taxonomic notes

The genus Serenoa honors Sereno Watson, an assistant of Asa Gray. Repens refers to the plant's creeping habit.[1]

Description

A description of Serenoa repens is provided in The Flora of North America.

S. repens has been observed to have no true stem, with petiole spinescent below surface.[2]

Distribution

This species is distributed from South Carolina to southeastern Louisiana.[3] It is one of the most abundant species in Florida.[1] Typical individuals have green leaves, however, there is a form with blue leaves that can be found along the southeastern coast of Florida.[4]

Ecology

Habitat

In the Coastal Plain in Florida and Georgia, Serenoa repens occurs around sinkholes in oolite, on dunes in an understory of Pinus clausa, sandpine-evergreen oak scrubs, cabbage palm-hardwood hammocks, pine flatwoods, open slash pine woodlands, coastal hammocks, Baccharis flats, longleaf pine-scrub oak ridges, dried up ponds, and pine-oak woodlands. It has been found in disturbed areas such as open pastures, roadsides, and a newly planted slash pine plantation with deep sterile sandy soil.[2] It will occur on sites ranging from xeric to hydric and on soils ranging from strongly acidic to alkaline[5] and has been found on sandy loam and sand.[2]

S. repens reduced its crown cover and biomass in response to heavy silvilculture, clearcutting, roller chopping, chopping, disking, bedding, and planting slash pine in north Florida flatwoods.[6][7][8][9] This species has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished north Florida habitat that was disturbed by any of these practices. It also decreased its cover in response to restoration roller chopping with and without fire in southwest Florida pine savanna.[10] S. repens decreased its cover and stems per acre in response to chopping in south Florida pinelands.[11]

This species decreased its density in response to summer and winter roller chopping with and without burning in central Florida prairies.[12] However, in some areas of central Florida, the plant was unaffected by summer roller chopping alone. It showed no change in density in reestablished prairie habitat that was disturbed by this practice.[13] Additionally, S. repens reduced its height, cover, and density in response to roller chopping in central and south Florida flatwoods.[14]

Serenoa repens is frequent and abundant in the Peninsula and Panhandle Xeric Sandhills, Panhandle Silty Longleaf Woodlands, Xeric Flatwoods, North Florida Mesic Flatwoods, Central Florida Flatwoods/Prairies, Calcareous Savannas, and North Florida Wet Flatlands community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[15]

Associated species include Persea, Rapanea, Myrica, Ficus, and Ardisia.[2]

Phenology

S. repens reproduces vegetatively by sprouting from rhizomes and sexually.[16] It has been observed flowering from January through June with peak inflorescence in May and fruiting April through December.[2][17][18]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates.[19]

Seed bank and germination

Seedling growth and early development are slow and full establishment requires 2 to 6 years.[16] Foster (2012) agreed upon an earlier study where what was found was that seedlings showed a type 2 survivorship with a reasonably constant mortality rate. The adult individuals are extremely long lived and experience limited recruitment. In restoration sites, saw palmetto growth can be accelerated under certain conditions.[20] Seeds for this species were found viable in the seed bank of a Florida pine flatwoods community after 11 years of fire exclusion.[21]

Fire ecology

This species is very fire tolerant with populations of Serenoa repens known to persist through repeated annual burning.[22] Most fires defoliate and top-kill the flammable foliage which almost immediately resprouts.[16] Behm states that S. repens contains the highest fine, coarse and total fuel biomass as well as the greatest accumulated debris and total energy content of the ten common Florida understory species.[23] It is able to survive fire by resprouting from a persisten root crown and rhizomes. Winter burned stands recover faster than summer burned stands because of the longer period of growth before the next winter dormancy.[16] A study on Long Pine Key in Everglades National Park, Florida showed S. repens to flower and produce fruit from January to June within one year following a fire in April. However, it does not appear to depend on recent fire for flowering and fruiting, as it also flowered and produced fruit to a comparable degree in plots burned six years prior.[24]

Pollination and use by animals

Various Hymenoptera families were observed visiting flowers of Serenoa repens at the Archbold Biological Station. These include bees from the Apidae family such as Apis mellifera, Bombus impatiens, Epeolus glabratus, E. pusillus and E. zonatus, plasterer bees from the Colletidae family such as Colletes banksi, C. brimleyi, C. mandibularis, C. nudus and Hylaeus graenicheri, sweat bees from the Halictidae family such as Agapostemon splendens, Augochlora pura, Augochlorella aurata, Augochloropsis metallica, Halictus poeyi, Lasioglossum miniatulus, L. nymphalis, L. placidensis, L. puteulanum, Sphecodes heraclei, wasps from the Leucospididae family such as Leucospis affinis, L. birkmani, L. robertsoni and L. slossonae, leafcutting bees such as Megachile xylocopoides (family Megachilidae), spider wasps from the Pompilidae family such as Episyron conterminus posterus and Tachypompilus f. ferrugineus, thread-waisted wasps from the Sphecidae family such as Bicyrtes quadrifasciata, Cerceris blakei, C. flavofasciata floridensis, C. fumipennis, C. rozeni, C. rufopicta, Crabro hilaris rufibasis, Ectemnius decemmaculatus tequesta, E. maculosus, E. rufipes ais, Isodontia exornata, I. mexicana, Larra bicolor, Liris beata, L. muesebecki, Oxybelus decorosum, O. laetus fulvipes, Pseudoplisus phaleratus, Sceliphron caementarium, Stictiella serrata, Tachysphex apicalis, T. similis, Tachytes distinctus, T. guatemalensis, T. mergus, Tanyoprymnus moneduloides and Xysma ceanothae, and wasps from the Vespidae family such as Eumenes smithii, Euodynerus apopkensis, Mischocyttarus cubensis, Monobia quadridens, Pachodynerus erynnis, Parancistrocerus bicornis, P. salcularis rufulus, Polistes bellicosus, P. metricus, Stenodynerus beameri, S. lineatifrons, Vespula squamosa, Zethus slossonae, Z. spinipes.[25] Additionally, S. repens has been observed to host assassin bugs such as Apiomerus crassipes (family Reduviidae).[26]

This species is very important to a variety of animals. Raccoons, foxes, rats, gopher tortoises, white tail deer, black bears, and feral hogs feed on the drupes. Saw palmetto is also used in protection and habitat for the crested caracara, Florida burrowing owls, Florida mouse, Florida sandhill cranes, and the Florida scrub jay.[16] Florida black bears are known to use saw palmetto as a protective cover when giving birth.[1]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Saw palmetto is of little value to livestock forage and is considered a rangeland pest by ranchers. In order to remove excess saw palmetto, roller-drum choppers are used and pulled in tandem at offset angles or perpendicular to each other.[16] Due to seedlings slow growth and establishment, it has long been dismissed in Florida restoration projects. However, Foster and Schmalzer (2012) found that saw palmetto growth in a restoration site can be accelerated under certain conditions.[20] This species should avoid soil disturbance to conserve its presence in pine communities.[6][7][8][9][10][11][12][14]

Cultural use

Saw palmetto has been used for a variety of purposes. It is a source of tannin and the fruit can be used as a treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia or a diuretic. In WWII it was found to be an acceptable cork substitute, by processing the soft tissue from the stem.[27]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Bennett, B. C. and R. H. Judith (1998). "Uses of Saw Palmetto (Serenoa repens, Arecaceae) in Florida." Economic Botany 52(4): 381-393

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: November 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, L. Baltzell, Walter M. Buswell, Angus Gholson, J.P. Gillespie, Robert K. Godfrey, Bruce Hansen, JoAnn Hansen, R.D. Houk, Lisa Keppner, Robert Kral, O. Lakela, S.W. Leonard, Sidney McDaniel, Richard S. Mitchell, Chas. A. Mosier, Gwynn W. Ramsey, John K. Small, Alfred Traverse, H.R. Totten, David E. Wilson. States and Counties: Florida: Calhoun, Clay, Dade, Escambia, Franklin, Gadsden, Gulf, Hernando, Jackson, Lake, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Monroe, Orange, Palm Beach, Taylor, Washington. Georgia: Thomas. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ [[1]]Floridata. Accessed: March 15, 2016

- ↑ [[2]]University of Florida Extension

- ↑ McNab, W. H. and M. B. Edwards (1980). "Climatic Factors Related to the Range of Saw-Palmetto (Serenoa repens (Bartr.) Small)." The American Midland Naturalist 103(1): 204-208

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Conde, L.F., B.F. Swindel, and J.E. Smith. (1986). Five Years of Vegetation Changes Following Conversion of Pine Flatwoods to Pinus elliottii Plantations. Forest Ecology and Management 15(4):295-300.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Lewis, C.E., G.W. Tanner, and W.S. Terry. (1988). Plant responses to pine management and deferred-rotation grazing in north Florida. Journal of Range Management 41(6):460-465.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Schultz, R.P. and L.P. Wilhite. (1974). Changes in a Flatwoods Site Following Intensive Preparation. Forest Science 20(3):230-237.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Huffman, J.M. and P.A. Werner. (2000). Restoration of Florida Pine Savanna: Flowering Response of Lilium catesbaei to Fire and Roller-Chopping. Natural Areas Journal 20(1):12-23.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Moore, W.H. (1974). Effects of Chopping Saw-Plametto-Pineland Threeawn Range in South Florida. Journal of Range Management 27(2):101-104.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Watts, A. C. and G. W. Tanner. 2003. Fire and roller chopping have varying effects on dry prairie plant species (Florida). Ecological Restoration 21(3): 205-207.

- ↑ Watts, A. C. and G. W. Tanner. 2003. Fire and roller chopping have varying effects on dry prairie plant species (Florida). Ecological Restoration 21(3): 205-207.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Willcox, E. V. and W. M. Giuliano. 2010. Seasonal effects of prescribed burning and roller chopping on saw palmetto in flatwoods. Forest Ecology and Management 259: 1580-1585.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 [[3]]

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 13 DEC 2016

- ↑ Gunderson, L., D. Taylor and J. Craig 1983. Report SFRC-83/04 Fire effects on flowering and fruiting patterns of understory plants in pinelands of EVER. Everglades National Park, South Florida Research Center, Homestead, Florida,36 pg.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Foster, T. E. and P. A. Schmalzer (2012). "Growth of Serenoa repens Planted in a Former Agricultural Site." Southeastern Naturalist 11(2): 331-336

- ↑ Maliakal, S.K., E.S. Menges and J.S. Denslow. 2000. Community composition and regeneration of Lake Wales Ridge wiregrass flatwoods in retlation to time-since-fire. Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 127:125-138.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Behm, A.L., M.L. Buryea, A.J. Long, and W.C. Zipperer. 2004. Flammability of native understory species in pine flatwood and hardwood hammock ecosystems and implications for the wildland-urban interface. International Journal of Wildland Fire 13: 355-365.

- ↑ Gunderson, L., D. Taylor and J. Craig 1983. Report SFRC-83/04 Fire effects on flowering and fruiting patterns of understory plants in pinelands of EVER. Everglades National Park, South Florida Research Center, Homestead, Florida, 36 pg. URL: https://ufdcimages.uflib.ufl.edu/FI/83/25/63/47/00001/FI83256347.pdf

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [4]

- ↑ Wilder, E. A. and E. D. Kitzke (1954). "Waxy Constituents of the Saw Palmetto, Serenoa repens (Bartr.) Small." Science 120(3107): 108-109.