Opuntia humifusa

| Opuntia humifusa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Wayne Matchett, SpaceCoastWildflowers.com | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Caryophyllales |

| Family: | Cactaceae |

| Genus: | Opuntia |

| Species: | O. humifusa |

| Binomial name | |

| Opuntia humifusa (Raf.) Raf. | |

| |

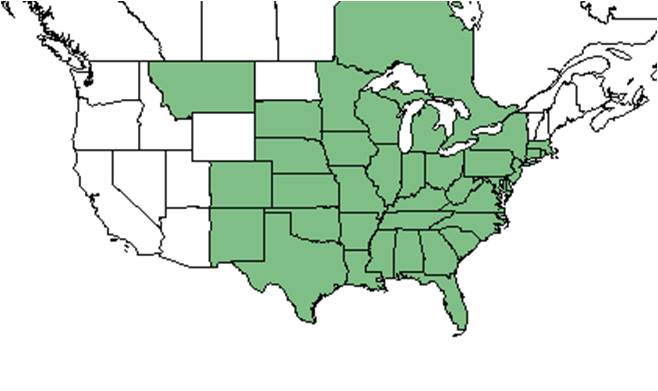

| Natural range of Opuntia humifusa from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Devil's-tongue; Eastern prickly pear[1]

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Opuntia compressa (Salisbury) J.F. Macbride var. compressa; O. impedita Small; O. macrarthra Gibbes; O. opuntia (Linnaeus) Karten; O. calcicola Wherry; O. rafinesquei Engelmann.[1]

Varieties: none.[1]

Description

A description of Opuntia humifusa is provided in The Flora of North America.

The leaves of Opuntia humifusa are 1.5-6 cm long, with the longest leaves having an acute to acuminate tip. The hairs of the leaf surfaces are similarly long and the leaf sheaths and culm axis are glabrate to pilose with hairs shorter than 1.5 mm. The awns are glabrous and the lemma is 9-11 veined.[1]

The root system of Opuntia humifusa includes stem tubers which store non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) important for both resprouting following fire and persisting during long periods of fire exclusion.[2] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an NSC concentration of 159.7 mg/g (ranking 32 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 47.2% (ranking 3 out of 100 species studied).[2]

Distribution

It is the only cactus to be widespread in the eastern United States.[3] It is mainly restricted to the Appalachian Mountains, in states like Deleware, Maryland, New Jersey, Virginia, and West Virginia, but also occurs in central and northcentral Mississippi. Further surveying could reveal populations in Alabama, northwestern Georgia, western South Carolina, western North Carolina, and northeastern Tennessee.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

Opuntia humifusa can occur in upland longleaf pines, sand dunes, Pinus clausa scrubs, open sand flats, sandhills, and pine/oak scrubs. It has been found in disturbed areas such as loblolly tree farms and roadside depressions. Associated species include Lyonia ferruginea, Lyonia lucida, Serenoa repens, Quercus geminata, Q. chapmanii, Persea humilis, Ceratiola, Osmanthus megacarpus, Rhynchospora megalocarpa, Galactia elliottii, and Smilax auriculata.[4] In Central Florida, O. humifusa exhibits no response to soil disturbance by some clearcutting. Bracket seeding, high-severity burn, and salvage logging. However, it responds positively to some clearcutting single roller chopping, and broadcast seeding.[5] It also responds both negatively or not at all to soil disturbance by roller chopping in Northwest Florida sandhills.[6]

It occurs in southern Canada, where average nighttime temperatures can reach -4 degrees Celsius. In order to prevent intracellular freeze dehydration and ice formation, individuals have an accumulation of sugars and mannitol in their cells.[7]

Phenology

O. humifusa has been observed flowering April through July with peak inflorescence in May and fruiting January, May, and December.[4][8]

Root stocks and detached cladodes can propagate vegetatively for up to 12 months after detachment.[7]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates.[9] The fruit is eaten and dispersed by birds, rabbits, woodrats, prairie-dogs, mice, ground squirrels, and white-tailed deer.[10]

Seed bank and germination

The germination rate is low.[10] O. humifusa is known to occur in above-ground vegetation and in the fall surveyed seed bank in the southern ridge sandhill regions in south-central Florida.[11]

Fire ecology

O. humifusa will resprout and recruit seedlings during post-fire recovery.[12]

Pollination

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Opuntia humifusa at Archbold Biological Station:[13]

Apidae: Apis mellifera, Bombus impatiens, B. pennsylvanicus, Mellisodes communis

Halictidae: Agapostemon splendens, Augochlorella aurata, Augochloropsis sumptuosa, Halictus poeyi, Lasioglossum nymphalis, L. puteulanum

Megachilidae: Dianthidium floridiense, Lithurgus gibbosus, Megachile brevis pseudobrevis, M. policaris

Use by animals

It is an important food for pocket gophers.[14] It is a host to the invasive cactus moth (Cactoblastis cactorum).[15] The large pads provides nesting to bobwhite quail.[16]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Native Americans used the pads to heal wounds, warts, and drank pad tea for respiratory issues.[3] It was also used as a poultice to stimulate milk supply in nursing mothers. The roots were used to stimulate hair growth and boiled with milk to treat dysentery, and a tea of the flowers could be used for urinary issues. A tea from the stem could be used in treating headaches, eyes problems, and insomnia.[17]

Photo Gallery

Flowers of Opuntia humifusa Photo by Wayne Matchett, SpaceCoastWildflowers.com

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: February 12, 2016

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: October 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Michael Blaker, M. Borgman, James R. Burkhaulter, George R. Cooley, R.J. Eaton, Patricia Elliott, J. Kevin England, Robert K. Godfrey, Darren Jackson, Ed Keppner, Lisa Keppner, Andrew McAllister, Sidney McDaniel, K.M. Meyer, James D. Ray Jr., Erik Robinson, L. Rosen, C.E. Smith, A. Townesmith, Kenneth A. Wilson, Carroll E. Wood Jr.. States and Counties: Alabama: Dale. Florida: Alabama, Escambia, Franklin, Gadsden, Hernando, Jackson, Lafayette, Leon, Liberty, Orange, Putnam, Seminole, Walton, Wakulla, Washington. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ Greenberg, C.H., D.G. Neary, L.D. Harris, and S.P. Linda. (1995). Vegetation Recovery Following High-intensity Wildfire and Silvicultural Treatments in Sand Pine Scrub. American Midland Naturalist 133(1):149-163.

- ↑ Hebb, E.A. (1971). Site Preparation Decreases Game Food Plants in Florida Sandhills. The Journal of Wildlife Management 35(1):155-162.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedgold - ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 12 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 [[2]] Accessed: February 13, 2016

- ↑ Lang, N. L. 2011. Soil seed bank dynamics of southern Lake Wales Ridge sandhill communities. Archbold Biological Station, Venus, Florida,15 pg.

- ↑ Lang, N. L. 2011. Soil seed bank dynamics of southern Lake Wales Ridge sandhill communities. Archbold Biological Station, Venus, Florida,15 pg.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Myers, G. T. and T. A. Vaughan (1964). "Food Habits of the Plains Pocket Gopher in Eastern Colorado." Journal of Mammalogy 45(4): 588-598.

- ↑ Jezorek, H. and P. Stiling (2012). "LACK OF ASSOCIATIONAL EFFECTS BETWEEN TWO HOSTS OF AN INVASIVE HERBIVORE: OPUNTIA SPP. AND CACTOBLASTIS CACTORUM (LEPIDOPTERA: PYRALIDAE)." The Florida Entomologist 95(4): 1048-1057.

- ↑ [[3]]Illinois Wildflowers. Accessed: February 15, 2016

- ↑ Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.