Ilex glabra

| Ilex glabra | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Wayne Matchett, SpaceCoastWildflowers.com | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Celastrales |

| Family: | Aquifoliaceae |

| Genus: | Ilex |

| Species: | I. glabra |

| Binomial name | |

| Ilex glabra (L.) A. Gray | |

| |

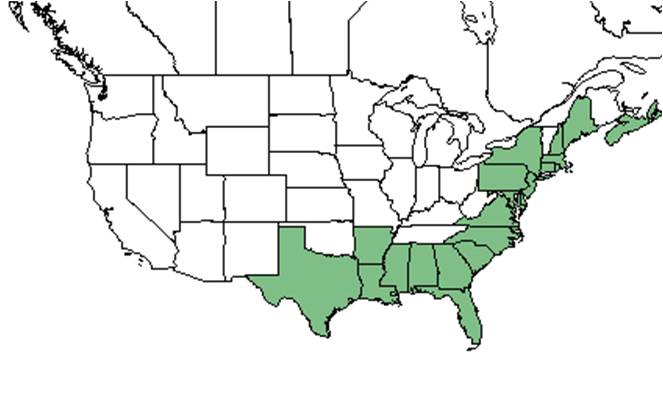

| Natural range of Ilex glabra from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Inkberry; Little gallberry[1]

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: none.[1]

Varieties: none.[1]

Description

“Trees or shrubs, usually with imperfect flowers. Leaves simple, entire, serrate, dentate or crenate; stipules obsolete. Flowers axillary, solitary, fascicled or in cymes, 4-7 merous, 4-8 mm broad; petals united at the base, imbricate in bud; pistillate flowers usually with nonfunctional stamens; anthers opening lengthwise; stigmas 4-7, essentially sessile. Drupe red, black or rarely yellow or white. Seeds with hard, bony endocarp (pyrenes), often grooved or ribbed on the back, 4-7 in a fruit, 1 in each locule.”[2]

"Rhizomatous shrub to 3m tall, usually forming extensive colonies, twigs puberulent. Leaves evergreen, obovate to elliptic, 2.5-6.5 cm long, crenate, but usually only toward the apex, the last pair of teeth usually directly opposite each other, glabrous, lustrous above; petioles 38 mm long, canescent. Pedicels 1-5 mm long, appearing longer when single fruited (careful examination shows that the lower part is peduncle). Staminate flowers in axillary, 3-7 flowered, pedunculate cymes. Pistillate flowers axillary, solitary or in 3-flowered, pedunculate cymes. Flowers 5-7 merous. Drupe black, dull or slightly lustrous, globose, 5-7 in diam.; pyrenes 5-7, smooth, 3-4 mm long."[2]

Average maximum root depth was found to be 6 cm, and average root porosity was found to be 20%.[3]

Distribution

Ilex glabra is distributed from Nova Scotia and Maine south to Florida and west to Texas.[4]

Ecology

Various species in the Ilex genus, including this species, contain a mixture of the alkaloid theobromine that is caffeine-like, actual caffeine, and various glycosides. This gives the opportunity to use this species as a potential caffeine crop that can be used to make beverages.[5]

Habitat

Ilex glabra can be found in "savannas, pine flatwoods, pocosin margins, swamps, primarily in wetlands, but extending upslope even into sandhills, with a clay lens or spodic horizon below to maintain additional moisture."[4] It is restricted to native groundcover with a statistical affinity in upland pinelands of South Georgia.[6] It is a dominant species in well-drained pocosin and bayland community sites, and is considered a very conspicuous species in longleaf pine communities in Florida. The species is shade tolerant, and can grow in full sun or shady areas, dry or wet areas, and on soils from sandy to heavy peat.[5] It is also tolerant of flooding.[7] This species has also been observed in a variety of habitats, including flatwoods, intermittent standing water, marsh edges, scrub thickets, cypress swamps, sand ridges, hammocks, branch bays, riverbanks, pinelands and savannas, lowlands, wet prairies, pine barrens, hillside bogs, low wetland swales, and some disturbed areas such as lots and tram roads. Soils observed ranged from moist sandy and loamy soil to drying sand and sandy peat.[8] In the Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plain, this species is listed by the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service as a facultative wetland species that mostly occurs in wetland habitats, but can also occasionally be found in non-wetland habitats.[9] A study by Brockway and Lewis found I. glabra to be negatively affected by clearcutting the overstory.[10] Another study found this species to also be negatively affected by disturbances such as stump removal, shearing and piling, discing, and bedding.[11] I. glabra responds mostly negatively--although not at all a very marginal amount of the time--to heavy silvilculture in North Florida.[12] It also responds both positively and negatively to soil disturbance by clearcutting and roller chopping in North Florida.[13] I. glabra responds negatively to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.[14] I. glabra responds negatively to soil disturbance by disking, bedding, and planting slash pines in North Florida flatwoods.[15]

Associated species include Pinus palustris, Aristida tussocks, Aristida stricta, Aristida sp., Ilex coriacea, Ilex cassine, Lobelia brevifolia, L. nuttallii, Polygala brevifolia, P. ramosa, Eriocaulon decangulare, Lycopodium carolinianum, Rhynchospora sp., Utricularia juncea, Serenoa repens, Senecio sp., Sarracenia sp., Hypericum sp., Baptisia alba, Quercus laevis, and various sedges.[8]

Ilex glabra is frequent and abundant in the Panhandle Silty Longleaf Woodlands, North Florida Mesic Flatwoods, Central Florida Flatwoods/Prairies, Calcareous Savannas, North Florida Wet Flatlands, Upper Panhandle Savannas, Lower Panhandle Savannas, and Panhandle Seepage Savannas community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[16]

Phenology

Generally, I. glabra flowers from May until June and fruits from September until November.[4] It has been observed to flower from April to June with peak inflorescence in May.[17] It has also been observed fruiting all year round.[8]

Seed dispersal

Due to the use of Ilex glabra by wildlife as well as its ability to colonize a wide variety of habitats, it is thought that the seeds are dispersed by animals.[5] This species is thought to be seed dispersed by various birds.[18]

Seed bank and germination

Seeds of this species can stay dormant in the seed bank for years, where germination could not occur for 2 to 3 years at most.[5] Even though the seeds exhibit a dormancy and patience is important for germination, treating the seeds for 30 to 60 days at 68 to 86 degrees followed by 60 to 90 days at 41 degrees can somewhat benefit germination as well.[7]

Fire ecology

This species has been observed in habitats that were recently burned.[8] It is a common component of "fire-climax communities", and can commonly invade frequently burned sites. Fire disturbance top-kills the plant, which makes it adapted to recurrent fire regimes. While low intensity fires can only kill recent growth, fire disturbance usually kills the aerial portion of the stem. Resprouting from fire occurs through the rhizomes and root crowns of the plant, and is most vigorous during the first year after a fire disturbance. In terms of fire seasonality, summer burn regiments are the most damaging for this species follwed by winter burn regiments.[5] While summer burns are the most damaging, they are also the most beneficial for overall occurrence and biomass of the species after fire.[19] As well, recovery of this species after a fire disturbance was found to reach original size 36 months post-burn.[20] A study by Abrahamson in the Lake Wales Ridge in Florida found crown width and height to significantly increase over time since fire disturbance in a swale habitat, but not as drastic of a change in a flatwoods habitat. However, fire disturbance was found to decrease this species' importance compared to other rare species.[21] While they found these rare species, like Gaylussacia dumosa and Vaccinium myrsinites, to rapidly increase immediately after fire disturbance, Ilex glabra over time overtopped these species in height and abundance.[22] A study on the overall flammability of the plant found that this species has a high foliar energy content, moderate levels of volatile solids, and a great amount of foliar biomass. These foliar volatile compounds were found to be more flammable and release more energy than most other species that live in the same habitat. With this, it is considered hazardous to structures in the wildland-urban interface due to its greater foliar energy content.[23]

Pollination

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Ilex glabra at Archbold Biological Station:[24]

Apidae: Apis mellifera, Bombus griseocollis, B. impatiens, Epeolus erigeronis, E. glabratus, E. pusillus, E. zonatus

Colletidae: Colletes banksi, C. brimleyi, C. distinctus, C. mandibularis, C. nudus, C. sp. A., C. thysanellae, Hylaeus confluens, H. schwarzi

Halictidae: Agapostemon splendens, Augochlora pura, Augochloropsis metallica, Halictus poeyi, Lasioglossum coreopsis, L. miniatulus, L. nymphalis, L. pectoralis, L. placidensis, L. puteulanum, Sphecodes brachycephalus

Leucospididae: Leucospis affinis, L. slossonae

Megachilidae: Anthidiellum notatum rufomaculatum, A. perplexum, Anthidium maculifrons, Coelioxys sayi, Dianthidium floridiense, Megachile brevis pseudobrevis, M. exilis parexilis, M. mendica, M. petulans, M. rugifrons, M. xylocopoides

Pompilidae: Ageniella partita, Anoplius krombeini, Episyron conterminus posterus, Priocnemis cornica, Psorthaspis legata, Sericopompilus apicalis

Sphecidae: Alysson melleus, Bembecinus nanus floridanus, Bembix sayi, Bicyrtes quadrifasciata, Cerceris bicornuta, C. blakei, C. flavofasciata floridensis, C. fumipennis, C. rufopicta, Crabro arcadiensis, Ectemnius rufipes ais, Gorytes dorothyae ruseolus, Isodontia auripes, I. exornata, I. mexicana, Larropsis greeni, Liris muesebecki, Microbembex monodonta, Miscophus americanum, M. slossonae slossonae, Oxybelus laetus fulvipes, Palmodes dimidiatus, Sphex ichneumoneus, Stictiella serrata, Tachysphex apicalis, T. similis, Tanyoprymnus moneduloides, Trypargilum clavatum johannis, T. collinum

Vespidae: Eumenes fraternus, E. smithii, Leptochilus alcolhuus, L. krombeini, L. republicanus, Mischocyttarus cubensis, Monobia quadridens, Pachodynerus erynnis, Parancistrocerus fulvipes rufovestris, P. salcularis rufulus, Polistes dorsalis hunteri, Stenodynerus fundatiformis, S. lineatifrons, Vespula squamosa, Zethus slossonae, Z. spinipes

Other species in the Hymenoptera order observed pollinating this species include Perdita floridensis, Augochloropsis anonyma, Dialictus coreopsis, D. miniatulus, D. nymphalis, D. placidensis, D. tegularis, Sphecodes heraclei, Megachile albitarsis, M. policaris, M. texana, Xylocopa micans, and X. virginica krombeini.[25] Overall, this species is considered by pollination ecologists to be of special value to honey bees since it attracts such large numbers for pollination.[7]

Use by animals

It consists of approximately 5-10% of the diet for various large mammals, small mammals, and terrestrial birds.[26] This plant is foraged by white-tailed deer, marsh rabbit, raccoon, opossum, coyote, bobwhite quail, wild turkey, and other species of birds. It provides cover for small rodents, some birds, and white-tailed deer. The nectar from the flowers is also an important source for production of honey.[5] This species is considered one of the most important fruit-yielding plants for supporting wildlife in Georgia flatwoods communities.[27]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

This species is listed as threatened by the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection and by the Maine Department of Conservation, Natural Areas Program. It is also listed as exploitably vulnerable by the New York Department of Environmental Conservation, Division of Land and Forests, and is listed as extirpated by the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources.[9] It is also considered critically imperiled in Texas, and possibly extirpated in New Hampshire.[28] For management of controlling the species, fire can be used as a tool to reduce the overall population. This can be achieved by successive fires, which can effectively kill the plant, and summer or winter burns can be applied for effective control of the species.[5] In managing for supplemental feeding of livestock, this species might be desirable to eradicate since it is mostly unpalatable and increases fire hazard as well as decreasing herbage production.[29]

This species can be used in restoration efforts for erosion control, phosphate mine reclamation, and watershed protection.[5]

Cultural use

Medicinally, the leaves are considered an astringent, and the fruit are considered emetic and a tonic.[30]

The leaves can be used for tea as they contain caffeine.[31]

Photo Gallery

Flower of Ilex glabra Photo by John R. Gwaltney

Fruit of Ilex glabra Photo by John R. Gwaltney

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 679-84. Print.

- ↑ Brewer, J. S., et al. (2011). "Carnivory in plants as a beneficial trait in wetlands." Aquatic Botany 94: 62-70.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Nesom, G. and G. Guala. (2003). Plant Guide: Inkberry Ilex glabra. N.R.C.S. United States Department of Agriculture. Baton Rouge, LA.

- ↑ Ostertag, T.E., and K.M. Robertson. 2007. A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, South Georgia, USA. Pages 109–120 in R.E. Masters and K.E.M. Galley (eds.). Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: May 30, 2019

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: May 2019. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, W. M. B., Tom Barnes, - Britten, Leffie Carlton, Bill Carr, K. Craddock Burks, Robert Christensen, A. F. Clewell, Richard R. Clinebell II, H. S. Conard, George R. Cooley, - Cruz, A. H. Curtiss, Delzie Demaree, Richard J. Eaton, William B. Fox, Elizabeth Gibson, J. P. Gillespie, Robert K. Godfrey, Liz Graf, Bruce Hansen, JoAnn Hansen, Violet Hicks, B. K. Holst, C. Jackson, R. Komarek, R. Kral, H. Kurz, O. Lakela, S. W. Leonard, Sidney McDaniel, K. M. Meyer, Joseph Monachino, - Montero, N. Annette Morris, Chas. A. Mosier, T. Myint, J. B. Nelson, R. A. Norris, William Platt, Elmer C. Prichard, James D. Ray, Jr., P. L. Redfearn, P. L. Redfearn, Jr., Valerie Renard, Raul Rivero, R. L. Scott, Cecil R. Slaughter, John K. Small, C. E. Smith, Francis Thorne, A. Townesmith, E. Tyson, John Utley, Kathy Utley, D. B. Ward, Roomie Wilson, C. E. Wood, Jean W. Wooten, and B. T. Y. States and Counties: Alabama: Conecuh. Florida: Alachua, Baker, Bradford, Calhoun, Citrus, Duval, Escambia, Flagler, Franklin, Gadsden, Glades, Gulf, Hillsborough, Jackson, Jefferson, Lake, Lee, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Martin, Okaloosa, Orange, Osceola, Palm Beach, Pasco, Polk, Putnam, Santa Rosa, Sarasota, Seminole, Taylor, Volusia, Wakulla, Walton, and Washington. Georgia: Thomas. Mississippi: Hancock.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 30 May 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ Brockway, D. G. and C. E. Lewis (2003). "Influence of deer, cattle grazing and timber harvest on plant species diversity in a longleaf pine bluestem ecosystem." Forest Ecology and Management 175: 49-69.

- ↑ Conde, L. F., et al. (1983). "Plant species cover, frequency, and biomass: Early responses to clearcutting, burning, windrowing, discing, and bedding in Pinus elliottii flatwoods." Forest Ecology and Management 6: 319-331.

- ↑ Conde, L.F., B.F. Swindel, and J.E. Smith. (1986). Five Years of Vegetation Changes Following Conversion of Pine Flatwoods to Pinus elliottii Plantations. Forest Ecology and Management 15(4):295-300.

- ↑ Lewis, C.E., G.W. Tanner, and W.S. Terry. (1988). Plant responses to pine management and deferred-rotation grazing in north Florida. Journal of Range Management 41(6):460-465.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Schultz, R.P. and L.P. Wilhite. (1974). Changes in a Flatwoods Site Following Intensive Preparation. Forest Science 20(3):230-237.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 12 DEC 2016

- ↑ Skeate, S. T. (1987). "Interactions between birds and fruits in a Northern Florida hammock community." Ecology 68(2): 297-309.

- ↑ Kush, J. S., et al. (2000). Understory plant community response to season of burn in natural longleaf pine forests. Proceedings 21st Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference. Fire and forest ecology: innovative silviculture & vegetation management, Tallahassee, FL, Tall Timbers Research, Inc.

- ↑ Schmalzer, P. A. and C. R. Hinkle (1992). "Recovery of Oak-Saw Palmetto Scrub after Fire." Castanea 57(3): 158-173.

- ↑ Abrahamson, W. (1984). "Post-Fire Recovery of Florida Lake Wales Ridge Vegetation." American Journal of Botany 71(1): 9-21.

- ↑ Abrahamson, W. G. (1984). "Species Responses to Fire on the Florida Lake Wales Ridge." American Journal of Botany 71(1): 35-43.

- ↑ Behm, A. L., et al. (2004). "Flammability of native understory species in pine flatwood and hardwood hammock ecosystems and implications for the wildland-urban interface." International Journal of Wildland Fire 13: 355-365.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Deyrup, M. J. E., and Beth Norden (2002). "The diversity and floral hosts of bees at the Archbold Biological Station, Florida (Hymenoptera: Apoidea)." Insecta mundi 16(1-3).

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Johnson, A. S. and J. L. Landers (1978). "Fruit production in slash pine plantations in Georgia." The Journal of Wildlife Management 42(3): 606-613.

- ↑ [[2]] NatureServe Explorer. Accessed: May 30, 2019

- ↑ Southwell, B. L. and L. K. Halls (1955). "Supplemental feeding of range cattle in longleaf-slash pine forests of Georgia." Journal of Range Management 8(1): 25-30.

- ↑ Nickell, J. M. (1911). J.M.Nickell's botanical ready reference : especially designed for druggists and physicians : containing all of the botanical drugs known up to the present time, giving their medical properties, and all of their botanical, common, pharmacopoeal and German common (in German) names. Chicago, IL, Murray & Nickell MFG. Co.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.