Vaccinium myrsinites

| Vaccinium myrsinites | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Pat Howell, Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Ericales |

| Family: | Ericaceae |

| Genus: | Vaccinium |

| Species: | V. myrsinites |

| Binomial name | |

| Vaccinium myrsinites Lam. | |

| |

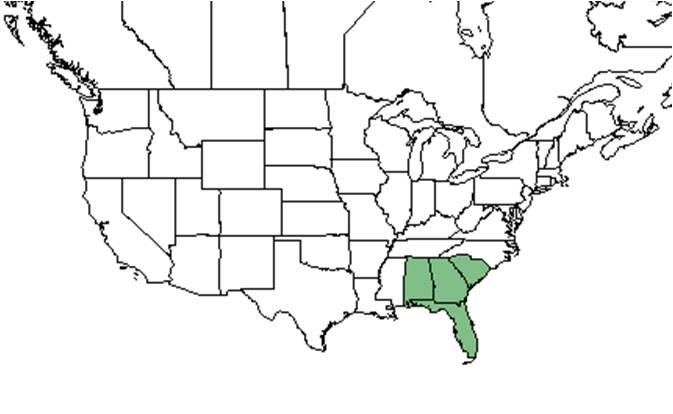

| Natural range of Vaccinium myrsinites from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Shiny blueberry, Southern evergreen blueberry

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonym: Cyanococcus myrsinites (Lamarck) Small var. myrsinites.[1]

Description

A description of Vaccinium myrsinites is provided in The Flora of North America.

Vaccinium myrsinites does not have specialized underground storage units apart from its taproot.[2] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an non-structural carbohydrate concentration of 97.7 mg/g (ranking 53 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 34.7% (ranking 78 out of 100 species studied).[2]

Distribution

Ecology

Habitat

V. myrsinites responds both positively and negatively to heavy silvilculture in North Florida.[3] When exposed to soil disturbance by military training in West Georgia, V. myrsinites responds negatively by way of absence.[4] It also responds negatively to soil disturbance by agriculture in Southwest Georgia.[5] V. myrsinites responds both positively and negatively to soil disturbance by clearcutting and roller chopping in North Florida.[6] However, it responds negatively to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.[7]

Vaccinum myrsinites is frequent and abundant in the Xeric Flatwoods, North Florida Mesic Flatwoods, and Central Florida Flatwoods/Prairies community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[8]

Phenology

V. myrsinites has been observed to flower January to April with peak inflorescence in March.[9]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates.[10] In particular, it has been found to be dispersed by the gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus).[11]

Pollination

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Vaccinium myrsinites at Archbold Biological Station:[12]

Apidae: Nomada fervida

Halictidae: Agapostemon splendens, Augochlorella aurata, A. gratiosa, Augochloropsis anonyma, A. metallica, A. sumptuosa, Lasioglossum pectoralis

Leucospididae: Leucospis slossonae

Megachilidae: Coelioxys sayi, Megachile brevis pseudobrevis, M. mendica

Sphecidae: Ectemnius rufipes ais

Vespidae: Parancistrocerus salcularis rufulus, Pseudodynerus quadrisectus, Stenodynerus fundatiformis, S. histrionalis rufustus, S. lineatifrons

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Vaccinium myrsinites produces a berry that can be eaten raw or cooked into goods such as jellies or pies.[13]

Photo Gallery

Flowers of Vaccinium myrsinites Photo by Shirley Denton (copyrighted- use by photographer’s permission only), Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants

References and notes

- ↑ Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draf of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ Conde, L.F., B.F. Swindel, and J.E. Smith. (1986). Five Years of Vegetation Changes Following Conversion of Pine Flatwoods to Pinus elliottii Plantations. Forest Ecology and Management 15(4):295-300.

- ↑ Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170

- ↑ Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.

- ↑ Lewis, C.E., G.W. Tanner, and W.S. Terry. (1988). Plant responses to pine management and deferred-rotation grazing in north Florida. Journal of Range Management 41(6):460-465.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 14 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kay Kirkman, unpublished data, 2015.

- ↑ Carlson, J. E., E. S. Menges, and P. L. Marks. 2003. Seed dispersal by Gopherus polyphemus at Archbold Biological Station, Florida. Florida Scientist, v. 66, no. 2, p. 147-154.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Hardin, J.W., Arena, J.M. 1969. Human Poisoning from Native and Cultivated Plants. Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina.