Persea borbonia

| Persea borbonia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Rebekah D. Wallace, University of Georgia Bugwood.org | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Laurales |

| Family: | Lauraceae |

| Genus: | Persea |

| Species: | P. borbonia |

| Binomial name | |

| Persea borbonia (L.) Spreng. | |

| |

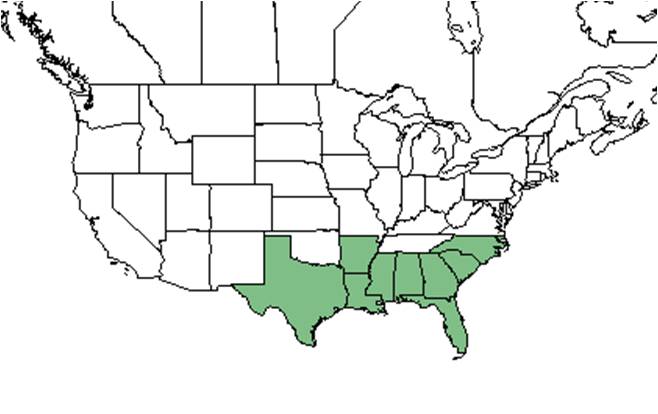

| Natural range of Persea borbonia from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Red bay

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Tamala borbonia (Linnaeus) Rafinesque; Persea borbonia var. borbonia

This species has had many scientific names since its discovery. The genus name Persea is derived from a Greek term for a Persian tree with fruits growing from the stem.[1]

Redbay is in the order Ranales (formally called Magnoliids). This order includes magnolias, yellow poplars, pawpaws, anise tree, wild cinnamon, and laurels.[1]

Description

A description of Persea borbonia is provided in The Flora of North America.

There are five different varieties of redbay in the southeastern U.S., they can be easily differentiated by the flower/fruit stem lengths, and trichomes on the abaxial leaf side.[1]

Distribution

The native distribution of redbay includes the Coastal Plain from south Delaware to Florida, west to southeast Texas, with isolated populations in central Texas.[2]

Ecology

Habitat

In the Coastal Plain in Florida, P. borbonia has been observed in cabbage palm-live oak hammocks, pine/scrub oak communities, mixed hardwood forests, vegetated shell mounds, tropical evergreen hardwood forests, dune thickets, oak-hickory-magnolia coastal hammocks, and wet pine flatwoods. It has been found in disturbed areas such as bulldozed turkey oak/longleaf pine communities and roadsides. [3] Redbay requires partial to fun sun, plenty of water supply, and root oxygen.[1] It does not tolerate long periods of inundation.[4] Soils are mostly Histosols.[5] It grows in loamy sand, sandy loam, and limestone substrate. P. borbonia does not respond to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.[6]

Associated species include Gordonia lasianthus, Quercus geminata, Celtis, Exothea paniculata, Xanthoxylum, Fagara, Persea littoralis, Rapanea guianensis, Parthenocissus quinquefolia, Plumbago scandens, Bumelia, Forestiera, Rhizophora, Baccharis halimifolia, black cherry and hackberry. [3]

Phenology

Flowers are perfect and monecious.[1] P. borbonia has been observed flowering April through June and fruiting January through July.[3][7] Cross-pollination is required for viable seeds.[1]

Seed dispersal

Seeds are dispersed by songbirds, white tailed deer, bobwhite, wild turkeys, and black bears.[5]

Seed bank and germination

Germination is hypogeal.[5] Seeds germinate well in mucky, swampy, and poorly drained areas; however, these conditions may be stressful to an adult tree. Adults require water and plenty of root oxygen which makes perminant inundated conditions damaging.[1]

Fire ecology

P. borbonia has been described as a late successional species that does not thrive in areas of disturbance such as fire.[1] Menges et al. (1993) found that P. borbonia densities and basal areas had increased in flatwoods and bayhead communitites that were fire suppressed for over 20 years. Fire may cause substantial damage to redbay; fire scarring and deterioration of the lower trunk portion of the tree is common.[5] However, a study on Long Pine Key in the Everglades found P. borbonia to resprout, flower, and fruit within about one year following a fire in April. The degree and timing of flowering and fruiting did not vary substantially among plots burned one, two, six, and seven years prior.[8]

Pollination

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Persea borbonia at Archbold Biological Station: [9]

Apidae: Apis mellifera, Bombus impatiens, Epeolus zonatus

Colletidae: Colletes banksi, C. brimleyi, C. nudus

Halictidae: Augochlora pura, Augochloropsis metallica, Lasioglossum pectoralis

Sphecidae: Cerceris fumipennis, Tachytes auricomans

Vespidae: Mischocyttarus cubensis, Pachodynerus erynnis, Parancistrocerus salcularis rufulus, Polistes metricus, Zethus spinipes

Use by animals

Fruits are a sizable portion of the bobwhite quail diet during fall and winter months.[5] Redbay rupes are eaten by songbirds, wild turkeys, quail, rodents, deer, and black bear. The leaves are also the primary larval food source for the palamedes swallowtail butterfly. Humans use redbay for carpentry trim, flavoring tea and gumbos, and medicinal purposes by Native Americans.[10]

Diseases and parasites

P. borbonia is susceptible to laurel wilt disease (LWD) which is a lethal vascular infection in trees of the laurel family cause by the fungus Raffaelea lauricola that is transported by the non-native ambrosia beetle Xyleborus glabratus. Laurel wilt disease is characterized by mortality of redbay stems in the infected sites. Distribution of LWD includes South Carolina, Georgia, Florida and parts of North Carolina. [11] The greatest decline in redbay populations is in Georgia (Fraedrich et al. 2008).

P. borbonia is also the primary host of a psyllid leaf-galler Trioza magnoliae, which produce galls on leaves. Galls use up resources that would otherwise be used for plant growth, therefore directly affecting plant fitness. [12]

It is resistant to the fungus Phytophthora cinnamomi which affects the roots of many other laurel species. This resistance is due to borbonol found in the roots and stems that is an antifungal substance.[5]

Conservation and management

Cultivation and restoration

The wood is often used for cabinetwork and lumber, while the leaves can be used to add spice and flavor to food.[2]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

Menges, E. S., W. G. Abrahamson, et al. (1993). "Twenty Years of Vegetation Change in Five Long-Unburned Florida Plant Communities." Journal of Vegetation Science 4(3): 375-386.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 [[1]]Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources. Accessed: February 20, 2016

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 [[2]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: February 19, 2016

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: October 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Delzie Demaree, R.J. Eaton, J.P. Gillespie, Robert K. Godfrey, Bruce Hansen, R. Komarek, Robert Kral, H. Kurz, O. Lakela, Elbert L. Little Jr., Sidney McDaniel, K.M. Meyer, Richard S. Mitchell, T. Myint, Jackie Patman, Elmer C. Prichard, Gwynn W. Ramsey, James D. Ray Jr., G. Robertson, Cecil R. Slaughter, Annie Schmidt, C.E. Smith, R.R. Smith, R.F. Thorne, A. Townesmith, Rodie White, C.E. Wood, Jean W. Wooten, Richard P. Wunderlin. States and Counties: Florida: Alachua, Brevard, Calhoun, Citrus, Columbia, Dade, Dixie, Flagler, Franklin, Gadsden, Jackson, Jefferson, Lee, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Marion, Martin, Nassau, Okaloosa, Osceola, Pasco, Pinellas, Suwannee, St. Johns, St. Lucie, Taylor, Volusia, Wakulla, Walton. Georgia: Grady. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ Conner, W. H. and R. A. George (1993). "Impact of Saltwater Flooding on Red Maple, Redbay, and Chinese Tallow Seedlings." Castanea 58(3): 214-219.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 [[3]]Accessed: February 19, 2016

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 12 DEC 2016

- ↑ Gunderson, L., D. Taylor and J. Craig 1983. Report SFRC-83/04 Fire effects on flowering and fruiting patterns of understory plants in pinelands of EVER. Everglades National Park, South Florida Research Center, Homestead, Florida, 36 pg.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Mayfield A.E. III 2007. Laurel Wilt: A serious threat to redbay and other related native plants. Palmetto 24(3):8-11.

- ↑ Shearman, T. M., G. Geoff Wang, et al. (2015). "Population dynamics of redbay (Persea borbonia) after laurel wilt disease: an assessment based on forest inventory and analysis data." Biology Invasions 17: 1371-1382.

- ↑ Leege, L. M. (2006). "The Relationship between Psyllid Leaf Galls and Redbay (Persea borbonia) Fitness Traits in Sun and Shade." Plant Ecology 184(2): 203-212.