Piptochaetium avenaceum

| Piptochaetium avenaceum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Guy Anglin, Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida – Monocotyledons |

| Order: | Cyperales |

| Family: | Poaceae ⁄ Gramineae |

| Genus: | Piptochaetium |

| Species: | P. avenaceum |

| Binomial name | |

| Piptochaetium avenaceum (L.) Parodi | |

| |

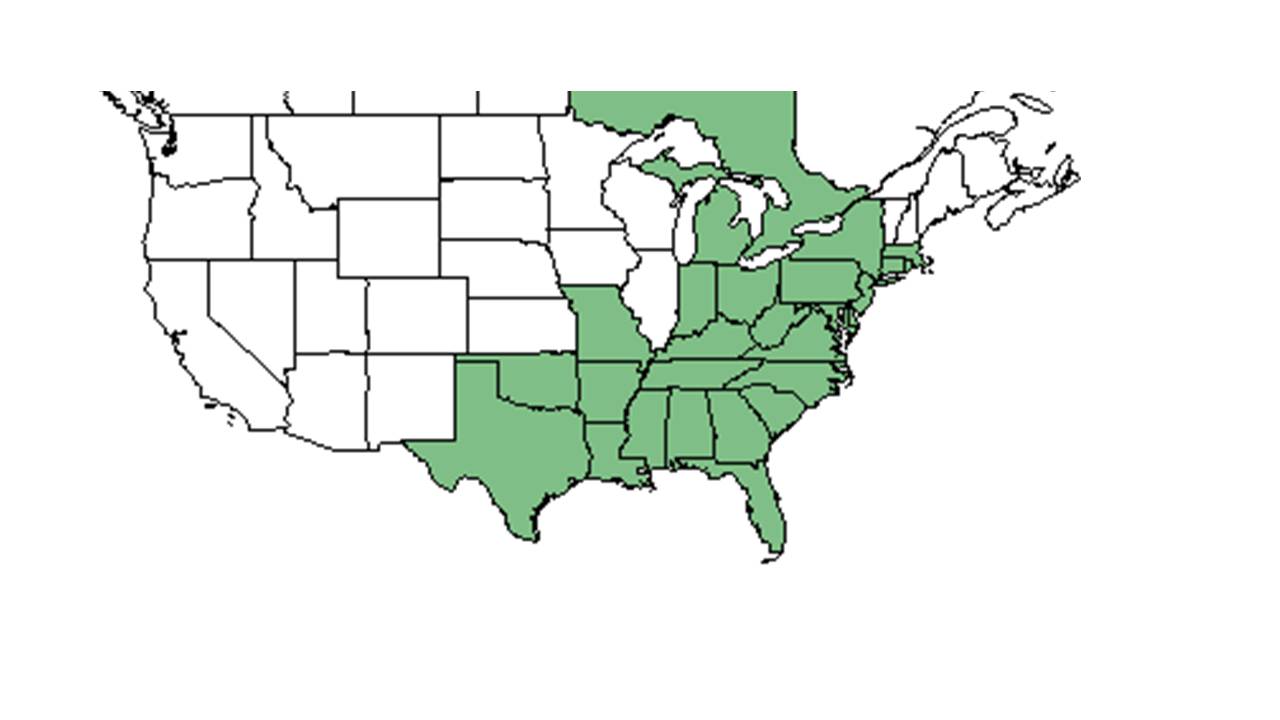

| Natural range of Piptochaetium avenaceum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Blackseed speargrass, Eastern needlegrass, Black oatgrass[1]

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Stipa avenacea Linnaeus.[1]

Varieties: none.[1]

Description

P. avenaceum is a cespitose perennial with culms that are 5-10 dm tall and glabrous nodes and internodes. The leaves are basal, with blades that are 3.5 dm long, 1-1.5 mm wides, scaberulous above and on the margins, and glabrous beneath. The sheaths are 2 mm long and have a glabrous texture, scarious margin and ligule. The open panicle is 1-3 dm long and 3-6 cm broad. The branches are ascending and scaberulous. Spikelets are 1-flowered, disarticulating above glumes, and 1 cm long (excluding the lemma awn). Glumes are scarious, acuminate to short-awned. The first glume is 3-nerved and 9-11 mm long, while the second glume is 5-nerved and 11-13 mm long. The lemmas are nerveless, brownish-purplish, lustrous, indurate, with scarious margins. Their bodies are 9-10 mm long and their awns are 4-6 cm long. The paleas are 9-10 mm long, scarious, glabrous, acuminate, with a brown hirsute callus. The grain is yellowish, linear, and 5-6 mm long.[2]

Distribution

This plant ranges from Massachusetts, Kentucky, southern Illinois, and central Oklahoma to central Florida and southern Texas. There are disjunct populations in northern Indiana and western Michigan.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

In the Coastal Plain in Florida and Georgia, Piptochaetium avenaceum is found in live oak groves, open sandy ridges, mesic coastal hammocks, woodland openings, floodplain edges, along creeks, lake slopes, upland mixed forests, mixed pinewoods, open mixed woodlands, annually burned savannas and pine-oak, open stand of shrubs and trees of Ilex vomitoria, and floodplains.[3] Human disturbed areas include roadsides, recreation areas, nature trails, stands of old field pines cleared of underbrush, and along city roads. It has been observed to grow in dry loamy sand, sandy soils, limestone outcrops, calcareous slopes and moist loamy sands.[3] P. avenaceum responds negatively to soil disturbance in old field longleaf communities in South Carolina.[4] It also responds negatively to agricultural-based soil disturbance in South Carolina coastal plain communities. This marks it as an indicator species for remnant woodland.[5][6]

Associated species include Melica mutica, Festuca, Erigeron, Verbena, Vitis rotundifolia, Rubus trivialis and Ilex vomitoria.[3]

Phenology

P. avenaceum flowers from April through June.[1]

Conservation and management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ Radford, A. E., Ahles, H. E., & Bell, C. R. (1968). Manual of the vascular flora of the Carolinas. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: July 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, K. MacClendon, T. MacClendon, Robert K. Godfrey, K. Craddock Burks, Jean W. Wooten, Swallen, George R. Cooley, Joseph Monachino, Gary R. Knight, Brenda Herring, Don Herring, Richard S. Mitchell, H. Kurz, Patricia Elliot, R. Komarek, R. A. Norris, Matt Hils, Annie Schmidt. States and Counties: Florida: Alachua, Calhoun, Escambia, Gadsden, Hernando, Holmes, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Liberty, Nassau, Okaloosa, St. Johns, Suwannee, Wakulla. Georgia: Grady, Thomas. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.