Dyschoriste oblongifolia

| Dyschoriste oblongifolia | |

|---|---|

| |

| photo by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Scrophulariales |

| Family: | Acanthaceae |

| Genus: | Dyschoriste |

| Species: | D. oblongifolia |

| Binomial name | |

| Dyschoriste oblongifolia (Michx.) Kunz | |

| |

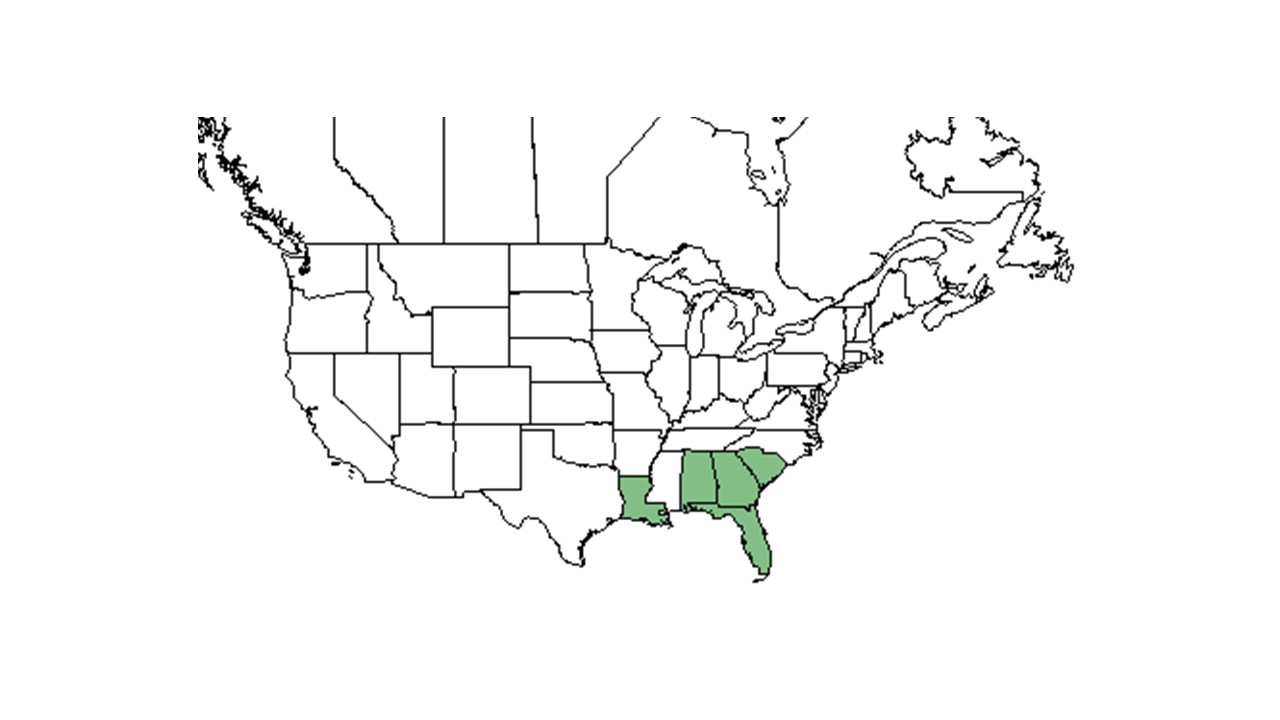

| Natural range of Dyschoriste oblongifolia. Image from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: oblongleaf snakeherb; oblongleaf twinflower; blue twinflower; pineland Dyschoriste

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonym: Dyschoriste oblongifolia (Michaux) Kuntze var. oblongifolia

Description

Dyschoriste oblongifolia is a perennial herb with opposite branches from elongate, slender rhizomes. Plant 1-5 dm tall; stems pilose. Leaves glabrate, oblanceolate to eliptic, to 4.5 cm long and 1.5 cm wide, entire or undulate, ciliate, sesslie or subsessile. Flowers subsessile, solitary or clustered in the leaf axils; bracts foliaceous, opposite, 15-18 mm long. Calyx pubescent, 15-20 cm long, tube short, lobes 5, linear-aristate; corolla 1.5-3 cm long, blue, funnelform, somewhat 2-lipped, lobes 5, 5-10 cm long; stamens 4, anther locules parallel; style to 1.5 cm long, 1-2 ovlues per locule, seeds 1 per locule, gray, ca. 2.5 mm broad. Capsules, brown, oblong, 12-14 mm long, ca. 3 mm in diameter. [1]

D. oblongifolia is a low-growing groundcover that spreads by underground runners.[2]

Distribution

The Florida distribution is provided by the Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants.

Ecology

Habitat

General habitats include pine flatwoods, savannas, and sandhills.[3] Indicator of native (unplowed) longleaf pine woodlands in upland Ultisol soils, and conversely rarely found on pasture or cultivated lands in that soil type[4][5][6]. Appears to be restricted to soils with a sandy A horizon, whether in Entisols (sandhills) or Ultisols (clayhills).[7] Where present in native longleaf pine-wiregrass habitats it is common and abundant.[8][5]

Dyschoriste oblongifolia has been found to be strongly associated with native groundcover as opposed to old-field groundcover upland pinelands of southern Georgia.[5] This species also has been observed in scrub environments, turkey oak barrens, wiregrass-palmetto flatwoods, mixed hardwood forests, mixed pine-hardwoods, and slopes and ridges of longleaf pine forests. [9] [10][11] It is abundant in longleaf pine communities.[12] Resides in upland, midslope, and lowland areas old growth longleaf pine/wiregrass sandhill habitat.[10] In deep sand soils it can grow in human disturbed areas such as recently cleared pine forests, ruderal edges of sandhills, roadsides, plowed areas, bulldozed areas, and open fields.[9] This suggests that its absence from Ultisols influenced by past agriculture may be in part due to changes in the soil structure associated with erosion of the sandy A horizon,[7] and it may also relate to loss of native ants that act as seed dispersers.[6] D. oblongifolia can grow in both full light and semi shaded environments in deep, loose, and/or loamy sands along ridges and generally flat areas.[9] It is also a characteristic species of the shortleaf pine-oak-hickory woodlands habitat in the Red Hills Region of north Florida and south Georgia.[13] D. oblongifolia responds negatively to soil disturbance in longleaf communities open to agriculture in the South Carolina coastal plains.[14] Its intolerance of agricultural-based soil disturbance marks it as an indicator species for remnant woodland.[15][16]

Although it spreads by runners, it does not compete well with larger and denser species.[2]

Associated species include Serenoa repens, Ilex glabra, Myrica, Aristida, Quercus laevis, Scutellaria multiglandulosa, Tephrosia virginiana.[9]

Phenology

D. oblongifolia generally flowers from April until May.[3] It germinates and flowers within a few weeks following fire at a wide range of burn dates, at least from March to July.[7] It has been observed to flower from March to November with peak inflorescence in April and May.[17][9] Kevin Robertson has observed this species flower within three months of burning. KMR

Seed dispersal

Seeds are dispersed by ants.[6] Although it spreads primiarily by underground runners, it does produce many seeds when its seed capsules split open.[2] This species is thought to be dispersed by ants and/or explosive dehiscence. [18]

Fire ecology

It has been found in both burned and unburned areas.[9] It resprouts rapidly after fire[12] and flowers predictably within one or two months following burning in the spring and summer.[7][19] Conversely, flowering is rather sparse and inconsistent in years without fire.[20]

Pollination

It attracts many pollinators, especially bees.[2]

Use by animals

It is a larval food sources for the common buckeye butterfly (Junonia coenia).[2] D. oblongifolia has been observed to be eaten by adult and juvenile gopher tortoises (Gohperus polyphemus).[21]

Diseases and parasites

Conservation and management

D. oblongifolia is critically imperiled in the state of Alabama.[22]

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ Radford, A.E., H.E. Ahles, and C.R. Bell. 1968. Manual of the vascular flora of the Carolinas. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. 1183 pp.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Huegel, Craig. [Florida Native Wildflowers] Accessed November 13, 2015

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ Brudvig, L. A. and E. I. Damschen (2010). "Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition." Ecography 34: 257-266.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Ostertag, T.E. and K.M. Robertson. 2007. A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, South Georgia, USA. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings 23:109-120.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Creech, M. N., L. K. Kirkman, et al. (2012). "Alteration and Recovery of Slash Pile Burn Sites in the Restoration of a Fire-Maintained Ecosystem." Restoration Ecology 20(4): 505-516.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Robertson, Kevin M. personal observation.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. K., M. B. Drew, et al. (1998). "Effects of experimental fire regimes on the population dynamics of Schwalbea americana L." Plant Ecology 137: 115-137.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Mast, A. R., A. Stuy, G. Nelson, A. Bugher, N. Weddington, J. Vega, K. Weismantel, D. S. Feller, and D. Paul. 2004 onward (continuously updated). Database of Florida State University's Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium. Website http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu/ [accessed 13 November 2015]. Collectors: Andre Clewell, Robert Godfrey, Robert Kral, P.L. Redfearn, Jr., William P. Adams, Loran Anderson, Richard Carter, H. Larry Stripling, S.W. Leonard, Gwynn W. Ramsey, R.S. Mitchell, George Cooley, James D. Ray, Jr., C.E. Wood, C.E. Smith, R.J. Eaton, Roy Komarek, Gary R. Knight, Mark A. Garland, C. Jackson, Mary Margaret Williams, T. Myint, Grady W. Reinert, Bill & Pam Anderson, John B. Nelson, R. L. Wilbur, C. R. Bell, Rodie White, R. A. Norris, D. C. Hunt, and Wilson Baker. States and Counties: Alabama: Heny. Florida: Charlotte, Citrus, Clay, Columbia, Gadsden, Jackson, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Marion, Orange, Pasco, Polk, Seminole, Suwannee, Taylor, Volusia, and Wakulla. Georgia: Bryan, Grady, McIntosh, Seminole, Sumter, and Thomas. South Carolina: Hampton and Jasper.

Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "FSU Herbarium" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 10.0 10.1 Gilliam, F. S., W. J. Platt, et al. (2006). "Natural disturbances and the physiognomy of pine savannas: A phenomenological model." Applied Vegetation Science 9: 83-96.

- ↑ Wade, K. A. and E. S. Menges (1987). "Effects of fire on invasion and community structure of a southern Indiana cedar barrens." Indiana Academy of Science 96: 273-286.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Simkin, S. M., W. K. Michener, et al. (2001). "Plant response following soil disturbance in a longleaf pine ecosystem." Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 128: 208-218.

- ↑ Clewell, A. F. (2013). "Prior prevalence of shortleaf pine-oak-hickory woodlands in the Tallahassee red hills." Castanea 78(4): 266-276.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 8 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Pavon, M. L. (1995). Diversity and response of ground cover arthropod communities to different seasonal burns in longleaf pine forests. Tallahassee, Florida A&M University.

- ↑ Robertson, Kevin M. observations at Pebble Hill Fire Plots on Pebble Hill Plantation near Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Mushinsky, H. R., Terri A. Stilson and Earl D. McCoy (2003). "Diet and Dietary Preference of the Juvenile Gopher Tortoise " Herpetologists' League 59(4): 475-486.

- ↑ [[1]] NatureServe Explorer. Accessed: May 3, 2019