Dichanthelium laxiflorum

| Dichanthelium laxiflorum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Shirley Denton (Copyrighted, use by photographer’s permission only), Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida – Monocotyledons |

| Order: | Cyperales |

| Family: | Poaceae ⁄ Gramineae |

| Genus: | Dichanthelium |

| Species: | D. laxiflorum |

| Binomial name | |

| Dichanthelium laxiflorum (Lam.) Gould | |

| |

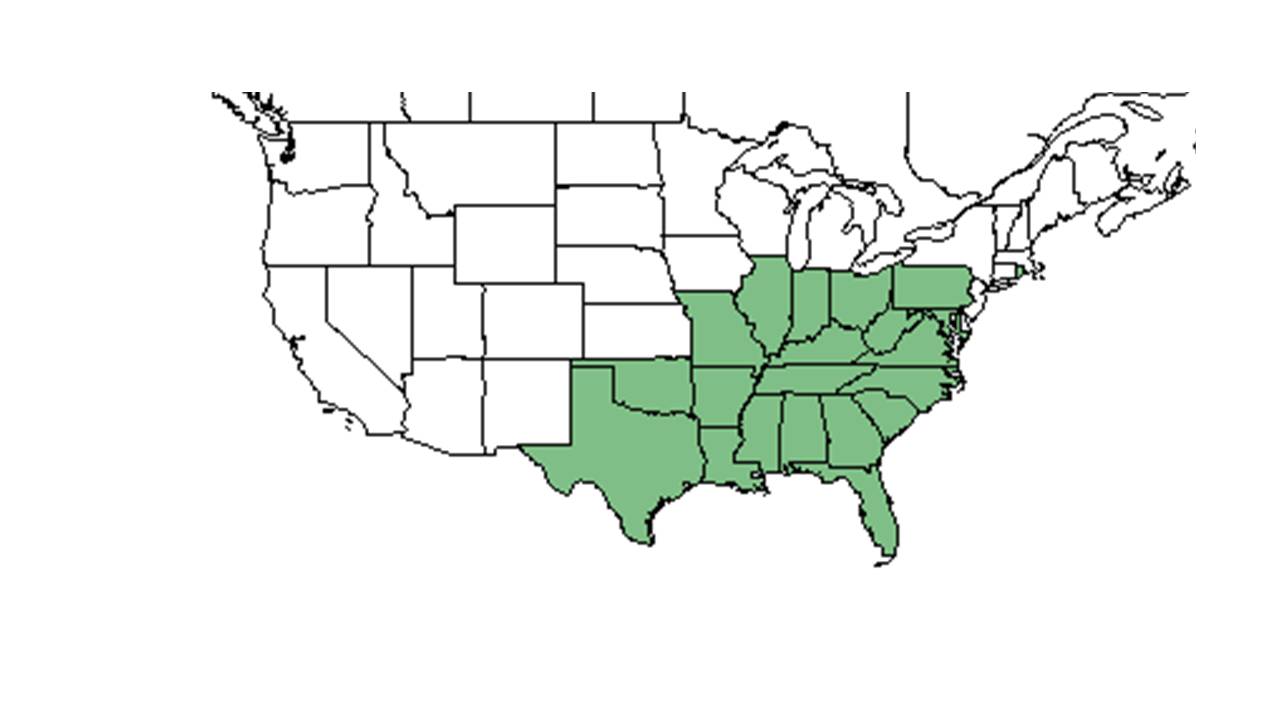

| Natural range of Dichanthelium laxiflorum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: openflower rosette grass

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Panicum laxiflorum Lam.; P. xalapense Humboldt, Bonpland, & Kunth var. xalapense; P. xalapense var. strictirameum A.S. Hitchcock & Chase; Panicum xalapense Kunth

Description

Dichanthelium laxiflorum is a perennial graminoid with a cespitose growth habit (FSU Herbarium).

Generally, for the Dichanthelium genus, they have "spikelets usually in panicles, round or nearly so in cross section, 2-flowered, terminal fertile, basal sterile, neutral or staminate. First glume usually present, 2nd glume and sterile lemma similar; fertile lemma and palea indurate without hyaline margins. Taxonomically our most difficult and least understood genus of grasses, more than 100 species an varieties are ascribed to the Carolinas by some authors. Note general descriptions for species groups (e.g., 1-4, 5-8, 9-13, and 26-62)." [1]

Specifically, for the D. laxiflorum species, they are "cespitose perennial; culms 1.5-4.5 dm tall, nodes usually bearded, internodes glabrous or scaberulous. Leaves mostly low cauline; blades to 16 cm long, 4-15 mm wide, glabrous or scaberulous. Leaves mostly low cauline; blades to 16 cm long, appressed to spreading-pilose; ligules ciliate, 0.5-1 mm long. Vernal panicle 4-9 cm long, 3-6 lipsoid, 1.6-2.3 mm long; pedicels smoothish, 1-10 mm long. First glume nerveless or 1-nerved, scarious, acute, 16-2.3 mm long. Sterile palea scarious, 1.2-1.6 mm long; fertile lemma and palea nerveless to faintly nerved, lustrous, yellowish to brownish, acute, 1.5-2 mm long. Grain whitish to yellowish, broadly ellipsoid, 1-1.5 mm long." [1]

Distribution

Ecology

Habitat

D. laxiflorum can live in disturbed areas such as clear-cuts, thinned woods, burned areas, roadsides, power line corridors, and old fields (FSU Herbarium), with clay to sandy loam soil in subtropical climates.[2] It can also dwell in dry areas,[3] like sandstone barrens communities.[3] It can be found in loblolly pine communities[4] and longleaf pine communities.[5] It also occurs in low ground hardwood communities, mesic hammocks, river banks, above lime sinks, on coastal hammocks, and near bogs (FSU Herbarium).

Associated species include Senecio, Krigia, Lolium, Hordeum, Tradescantia, Scleria, Diospyros, Rhus copallina, Hypericum mutilum, P. angustfolium, D. commutatum (FSU Herbarium).

Phenology

Flowering has been observed in January through May, and November, and fruiting has been observed in January through June, and November (FSU Herbarium).

Seed dispersal

It can be found in the seed bank of disturbed and undisturbed sites.[5] It can also be found in the seed bank of a Florida flatwoods plant community.[6] According to Kay Kirkman, a plant ecologist, this species disperses by gravity. [7]

Seed bank and germination

From observing the results of Taft's prescribed burns, fire seems to be required for germination.[3]

Fire ecology

This species has been found in frequently burned areas (FSU Herbarium).

In an experiment by Iglay, Leopold, Miller, and Burger, D. laxiflorum had a positive response to dormant season prescribed fire and to imazapyr, a herbicide.[2] Following an early dormant season, moderate-intensity burn in 1989, it rapidly increased, probably due to a stimulation if the seed bank. By 1995, D. laxiflorum occurred in 64% of the quadrants in Illinois and was the species with the greatest frequency, replacing Schizachyrium scoparium as the dominant species.[3]

Conservation and management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Bonnie Carswell, Kurt E. Blum, Sidney McDaniel, Lloyd H. Shinners, R. F. Thorne, R. A. Davidson, R. Kral, Raymond Athey, John B. Nelson, S. Bennett, T. Kohlsaat, D. Kennemore, Charles N. Horn, Carolyn Kindell, W ledbetter, R.K. Godfrey, K. Craddock Burks, J. B. Phipps, Sydney Thompson, R. F. Thorne, R. A. Davidson, A. H. Curtiss, Sidney McDaniel, James R. Burkhalter, Patricia Elliot, C. Jackson, H. Kurz, George R. Cooley, Joseph Monachino, R. Komarek, Cecil R Slaughter, Marie Victorin, Rolland Germain, Marcel Raymond, J. Kucyniak, and André. States and Counties: Alabama: Geneva and Pickens. Florida: Alachua, Calhoun, Franklin, Gadsden, Hernando, Holmes, Jackson, Jefferson, Lee, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Nassau, Palm Beach, Putnam, Santa Rosa, Taylor, Union, Walton, and Wakulla. Georgia: Decatur and Grady. Kentucky: Carlisle. Louisiana: East Feliciana. North Carolina: Wake. South Carolina: Abbeville, Fairfield, and Calhoun. Tennessee: Coffee. Texas: Freestone and Van Zandt. Other Countries: Canada

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 142-151. Print.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Iglay, R. B., B. D. Leopold, et al. (2010). "Effect of plant community composition on plant response to fire and herbicide treatments." Forest Ecology and Management 260: 543-548.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Taft, J. B. (2003). "Fire effects on community structure, composition, and diversity in a dry sandstone barrens." Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 130: 170-192.

- ↑ Miller, J. H. and K. V. Miller (1999). Forest plants of the southeast, and their wildlife uses Champaign, IL, Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Cohen, S., R. Braham, et al. (2004). "Seed bank viability in disturbed longleaf pine sites." Restoration Ecology 12: 503-515.

- ↑ Kalmbacher, R., N. Cellinese, et al. (2005). "Seeds obtained by vacuuming the soil surface after fire compared with soil seedbank in a flatwoods plant community." Native Plants Journal 6: 233-241.

- ↑ Kay Kirkman, unpublished data, 2015.