Ipomoea pandurata

| Ipomoea pandurata | |

|---|---|

Error creating thumbnail: Unable to save thumbnail to destination

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Solanales |

| Family: | Convolvulaceae |

| Genus: | Ipomoea |

| Species: | I. caroliniana |

| Binomial name | |

| Ipomoea pandurata (L.) G. Mey. | |

| |

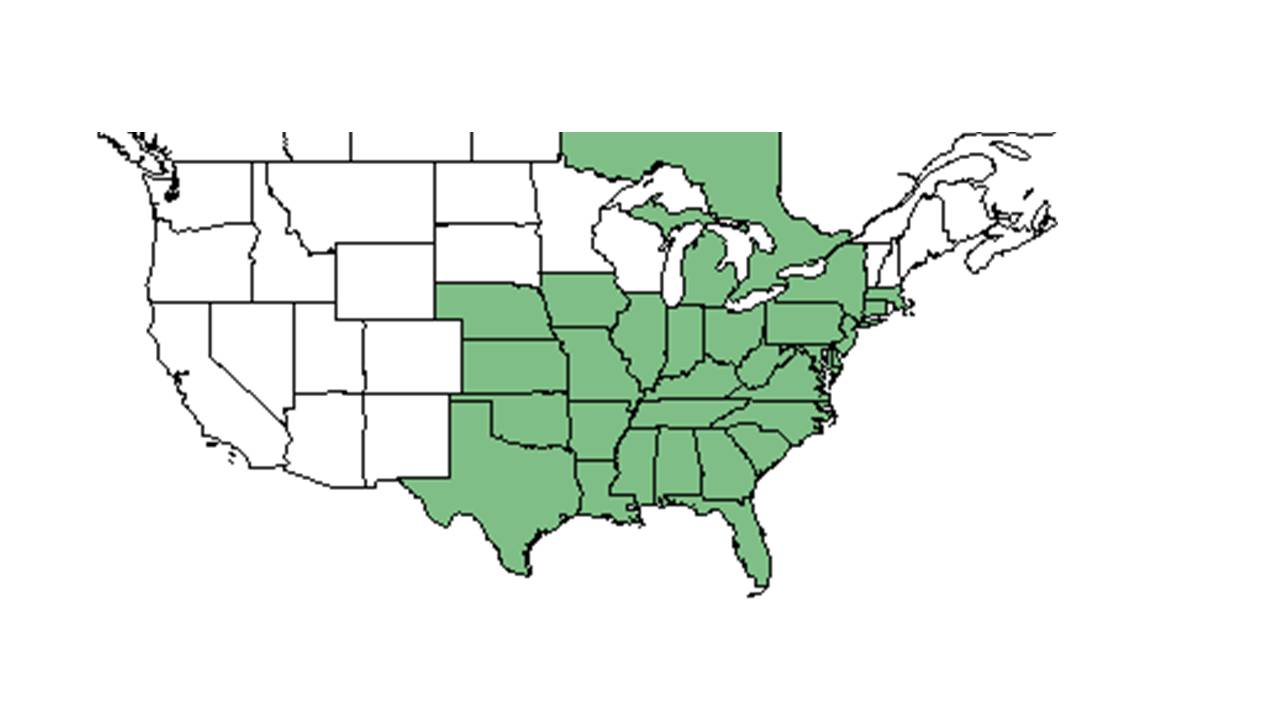

| Natural range of Ipomoea pandurata from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Description

Ipomoea pandurata, a perennial morning glory, has a large storage root and heart-shaped leaves (fig. 2). The plant forms one or more trailing vines that will grow along any surface. Produces a new shoot every year.[1]

Common Name: Carolina indigo

Distribution

Ecology

Net photosynthesis did not differ significantly among the disturbance levels. However, whether a site was burned in the previous year clearly influenced net photosynthesis. Low sites that had been burned recently tended to have lower net photosynthesis than unburned low disturbance sites. Recently burned medium sites had much higher net photosynthesis than unburned medium sites. The highest rate of photosynthesis occurred at the burned medium and high sites.[1] We found that recent prescribed burning, a management tool used to promote the growth of longleaf pine in this ecosystem, elevated levels of net photosynthesis for both ground cover species that we examined as stress indicators. In species with underground perennating organs, burning has been shown to stimulate rates of net photosynthesis (Schlesinger and Gill 1980; Oechel and Hastings 1983; Fleck et al. 1998).[2] Although a flush of nutrients immediately follows burning, with an increase in mineralized nitrogen potentially persisting for up to a year (Choromanska and DeLuca 2001)[3], most of the increase in net photosynthesis is believed to be the result of a change in the ratio of roots to shoots. The new smaller shoots have a proportionately larger root system that provides ample water and nutrients (Fleck et al. 1998).[4][1]

Habitat

This species does well in canopy openings in dry woods and thickets.[1] This species has also been observed to grow in open pine-oak scrub, along roadsides, and in open fields (FSU Herbarium).

Phenology

Seed dispersal

Seed bank and germination

Fire ecology

It appeared growing after a burn at the end of May/early June.[5] It occurs in mostly longleaf pine communities that are annually burned as well (FSU Herbarium).

Pollination

Use by animals

Diseases and parasites

Conservation and Management

Physical habitat disturbance was caused by activities associated with infantry training, including mechanized elements (tanks and personnel carriers) and foot soldiers. In addition, we examined the influence of prescribed burns and microhabitat effects (within meter-square quadrats centered about the plant) on these measures of plant stress. Net photosynthesis declined with increasing disturbance in the absence of burning for both species. However, when sites were burned the previous year, net photosynthesis increased with increasing disturbance.[1]

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014.

Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, R. F. Doren, R. Komarek, R. A. Norris, and Gwynn W. Ramsey.

States and Counties: Florida: Gadsden and Leon. Georgia: Brooks, Grady, and Thomas.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Freeman, D. C., M. L. Brown, et al. (2004). "Photosynthesis and fluctuating asymmetry as indicators of plant response to soil disturbance in the fall-line sandhills of Georgia: a case study using Rhus copallinum and Ipomoea pandurata." International Journal of Plant Sciences 165: 805-816.

- ↑ citation needed

- ↑ citation needed

- ↑ citation needed

- ↑ Arata, A. A. (1959). "Effects of burning on vegetation and rodent populations in a longleaf pine-turkey oak association in north central Florida." Quarterly Journal of the Florida Academy of Sciences 22: 94-104.