Liatris pilosa

| Liatris pilosa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae ⁄ Compositae |

| Genus: | Liatris |

| Species: | L. pilosa |

| Binomial name | |

| Liatris pilosa Willd. | |

| |

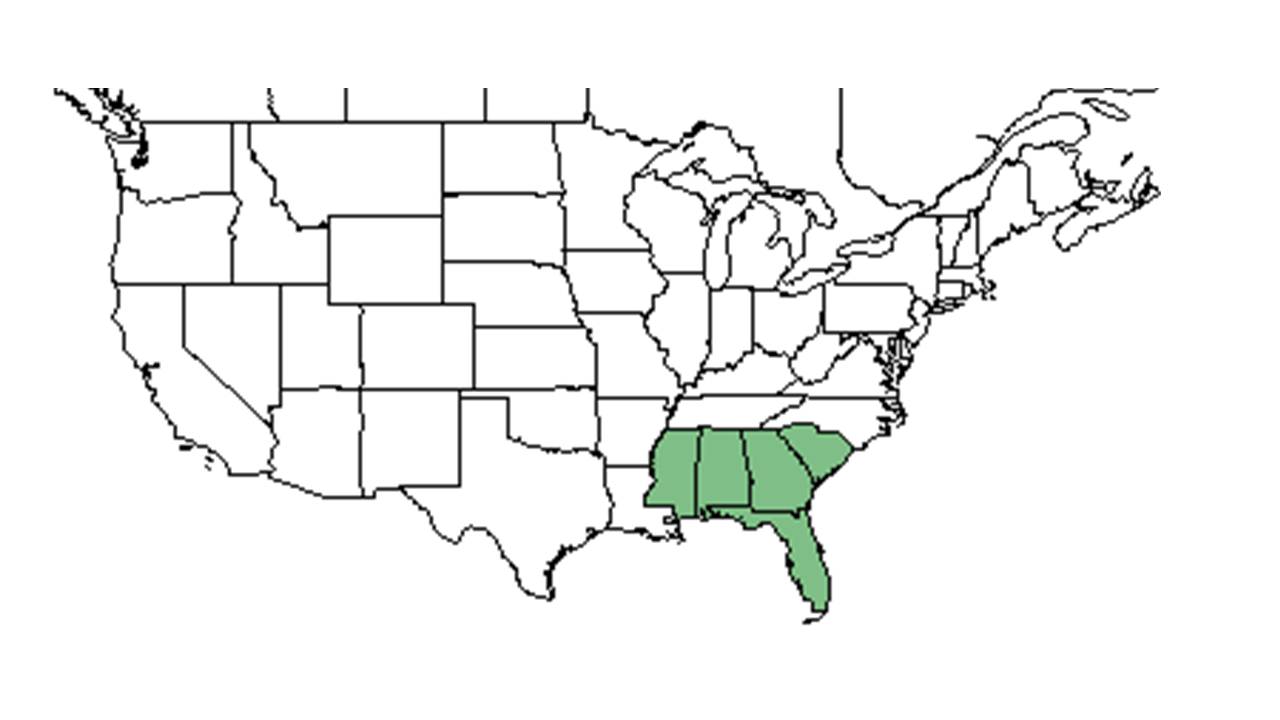

| Natural range of Liatris pilosa from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: shaggy blazing star; grass-leaf gayfeather; slender gayfeather

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Liatris graminifolia; Laciniaria graminifolia (Walter) Kuntze[1]

Varieties: L. graminifolia var. graminifolia; L. graminifolia var. lasia Fernald & Griscom; L. graminifolia var. racemosa (A.P. de Candolle) Venard; L. graminifolia var. typica; L. graminifolia var. dubia (Barton) A. Gray;.[1]

Description

This species is abundant where it is found.[2]

A description of Liatris pilosa is provided in The Flora of North America.

Distribution

The range of L. pilosa extends from New Jersey, Deleware, and Pennsylvania, then south to South Carolina.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

This species is found within well-drained stands of longleaf pine, sandhill slopes, and mixed hardwood-pine flatwoods as well as disturbed areas such as clear-cut slash pine plantations.[2] It has been observed to grow in open light conditions in red, sandy clays.[2]

L. pilosa became absent in response to soil disturbance by heavy silviculture in North Carolina and military training in west Georgia. It has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished longleaf pinelands that were disturbed by these practices.[3][4]

Phenology

This species has been observed flowering from September through October and fruiting in October.[2]

Fire ecology

This species grows in areas that are burned,[2] as populations of Liatris pilosa that have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[5][6]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

L. pilosa should avoid soil disturbance by heavy silvilculture and military training to conserve its presence in pine communities.[3][4]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "weakley" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "weakley" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: R. Kral, Wilson Baker, R. Komarek, Robert K. Godfrey, and Chris VanDerpoel. States and Counties: Florida: Gadsden, Leon, Levy, Liberty, and Taylor. Georgia: Grady and Thomas.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Cohen, S., R. Braham, and F. Sanchez. (2004). Seed Bank Viability in Disturbed Longleaf Pine Sites. Restoration Ecology 12(4):503-515.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.