Ipomoea pandurata

| Ipomoea pandurata | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Solanales |

| Family: | Convolvulaceae |

| Genus: | Ipomoea |

| Species: | I. pandurata |

| Binomial name | |

| Ipomoea pandurata (L.) G. Mey. | |

| |

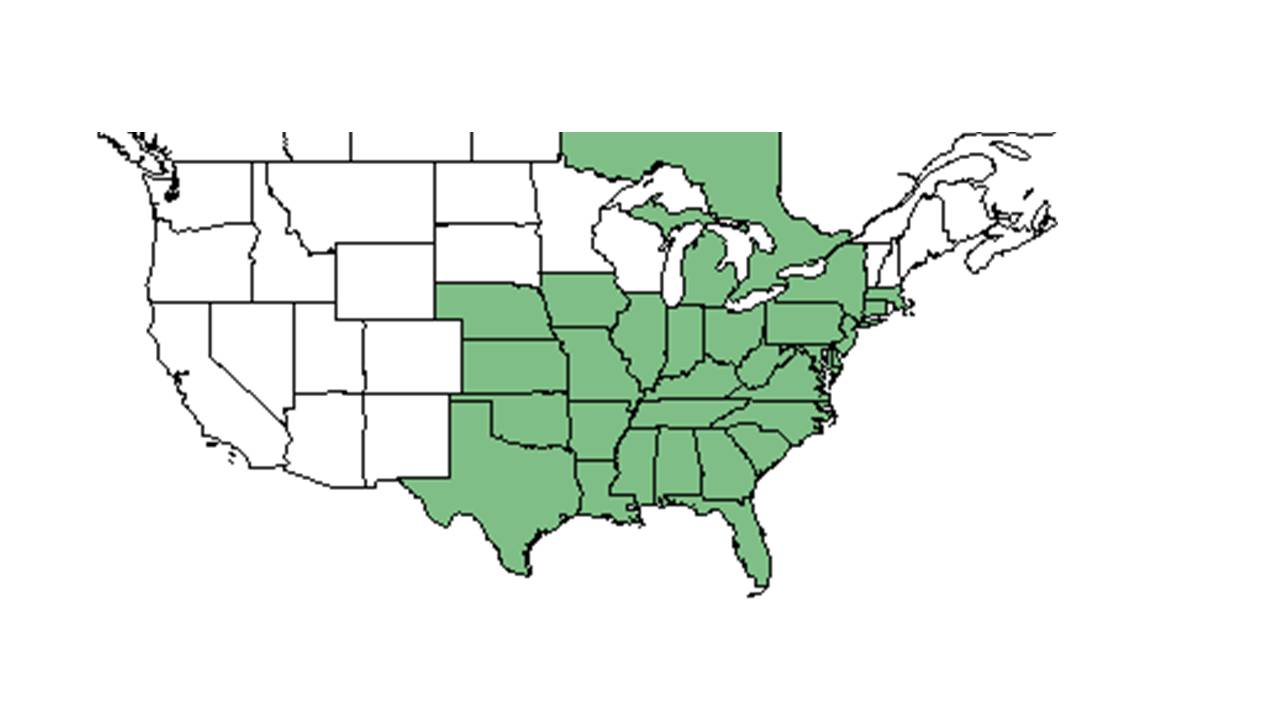

| Natural range of Ipomoea pandurata from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: man-of-the-earth, wild sweet potato, manroot[1]

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: none[1]

Varieties: Ipomoea pandurata var. pandurata; I. pandurata var. rubescens Choisy[1]

Description

Ipomoea pandurata is a perennial trailing vine, with heart-shaped leaves, has a large storage root, and makes a new shoot every year.[2] The storage root can exceed 20 kg and can be cooked and eaten.[3] This species thrives in canopy opening and in thickets.[2]

Herbaceous annual or perennial vines, or rarely a shrubby perennial. Flowers axillary, solitary, or in 2-5 flowered cymes. Calyx lobes 5, often imbricate; corolla campanulate to funnel-form, or salverform in 2 species; stamens 5, inserted in the corolla tube alternate with the lobes; stigma globose, entire or slightly lobed, style 1, ovary 2-or-4 locular. Capsule 2-4 valved; seeds 2-6, sometimes villous. A large genus of primarily tropical plants, some of which were introduced as horticultural plants and have escaped to become noxious weeds.[4]

Trailing, glabrate, or weakly pubescent perennial from an enlarged root. Leaves ovate, entire or pandurate, 3.5-8 cm long, 2.5-8 cm wide, cordate, often pubescent beneath. Peduncles 1-5 flowered; pedicel glabrous, stout; calyx lobes coriaceous, oblong-elliptic, 12-15 mm long, glabrous, strongly imbricate; corolla campanulate, 6-8 cm long, about as broad, the limb white, the tube lavender within; anthers 5-7 mm long, stamens and stigma included. Capsule ovoid, ca. 1 cm long; seeds villous on the angles.[4]

Distribution

This plant is found north in Connecticut, New York, and southern Ontario, west in Ohio, southern, Mississippi, and Kansas, then south in central peninsular Florida and east Texas.[1]

Ecology

It was observed that I. pandurata’s growth in recently-burned areas is low. However, in areas that are unburned and have low disturbance, it exhibits higher growth rates.[2]

Habitat

Ipomoea pandurata grows in well-drained uplands, sandhills, and open pine-oak scrub.[5][1] It is also observed to grow in disturbed areas, such as roadsides and open fields.[5] A study exploring longleaf pine patch dynamics found I. pandurata to be most strongly represented within longleaf pine gaps and under patches of longleaf that are up to 50 years of age.[6]

I. pandurata was found to be a decreaser in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[7]

Phenology

I. pandurata has been observed to flower from May to September with peak inflorescence in May and June.[8][5] Observed growing after a burn at the end of May/early June (Arata 1959).

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity.[9]

Fire ecology

Populations of Ipomoea pandurata have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[10] This species was observed growing after a burn at the end of May/early June.[11] It occurs in mostly longleaf pine communities that are annually burned as well.[5]

Pollination

Ipomoea pandurata has been observed to host pollinators from the Apidae family such as Anthophora abrupta, Bombus impatiens, B. pensylvanicus, B. vagans, Cemolobus ipomoeae, Melitoma taurea, and Peponapis pruinosa.[12]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Historically, the large sweet potato-like root of the plant has been consumed by Native Americans.[13]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Freeman, D. Carl, Michelle L. Brown, Jeffrey J. Duda, John H. Graham, John M. Emlen, Anthony J. Krzysik, Harold E. Balbach, David A. Kovacic, and John C. Zak. "Photosynthesis and Fluctuating Asymmetry as Indicators of Plant Response to Soil Disturbance in the Fall‐Line Sandhills of Georgia: A Case Study Using Rhus Copallinum and Ipomoea Pandurata." International Journal of Plant Sciences 165.5 (2004): 805-16. Web. 24 June 2013.

- ↑ Hammer, Roger. 2016. Posted to Florida Ecology and Ecosystematics Facebook Group, 11 JAN 2017.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 864-8. Print.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, R. F. Doren, R. Komarek, R. A. Norris, and Gwynn W. Ramsey. States and Counties: Florida: Gadsden and Leon. Georgia: Brooks, Grady, and Thomas.

- ↑ Mugnani et al. (2019). “Longleaf Pine Patch Dynamics Influence Ground-Layer Vegetation in Old-Growth Pine Savanna”.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 12 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Arata, A. A. "Effects of burning on vegetation and rodent populations in a longleaf pine-turkey oak association in north central Florida." Quarterly Journal of the Florida Academy of Sciences 22 (1959): 94-104.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.