Difference between revisions of "Desmodium laevigatum"

HaleighJoM (talk | contribs) (→Ecology) |

|||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

Populations of ''Desmodium laevigatum'' have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.<ref>Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.</ref><ref>Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.</ref> It has been observed in areas that are frequently burned<ref name= "fsu"/>, but has also been found in areas that are fire excluded which means it is not fully fire dependent.<ref>Clewell, A. F. (2014). "Forest development 44 years after fire exclusion in formerly annually burned oldfield pine woodland, Florida." Castanea 79: 147-167.</ref> For fire seasonality, one study found greatest abundance after a summer burn rather than a spring burn.<ref>Cushwa, C. T., et al. (1970). Response of legumes to prescribed burns in loblolly pine stands of the South Carolina Piedmont. Asheville, NC, USDA Forest Service, Research Note SE-140: 6.</ref> | Populations of ''Desmodium laevigatum'' have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.<ref>Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.</ref><ref>Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.</ref> It has been observed in areas that are frequently burned<ref name= "fsu"/>, but has also been found in areas that are fire excluded which means it is not fully fire dependent.<ref>Clewell, A. F. (2014). "Forest development 44 years after fire exclusion in formerly annually burned oldfield pine woodland, Florida." Castanea 79: 147-167.</ref> For fire seasonality, one study found greatest abundance after a summer burn rather than a spring burn.<ref>Cushwa, C. T., et al. (1970). Response of legumes to prescribed burns in loblolly pine stands of the South Carolina Piedmont. Asheville, NC, USDA Forest Service, Research Note SE-140: 6.</ref> | ||

| − | ===Pollination and | + | <!--===Pollination===--> |

| + | |||

| + | ===Herbivory and toxicology===<!--Herbivory, granivory, insect hosting, etc.--> | ||

''Desmodium laevigatum'' consists of approximately 10-25% of the diet for large mammals and terrestrial birds.<ref>Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.</ref> ''D. laevigatum'' has been recorded as a food source for white-tailed deer as well as northern bobwhite quail.<ref>Atwood, E. L. (1941). "White-tailed deer foods of the United States." The Journal of Wildlife Management 5(3): 314-332.</ref><ref>Hamrick, R., et al. (2007). Ecology & management of northern bobwhite. Publication 2179. Mississippi State, MS, Mississippi State University [Extension Service of Mississippi State University, cooperating with U.S. Department of Agriculture].</ref> | ''Desmodium laevigatum'' consists of approximately 10-25% of the diet for large mammals and terrestrial birds.<ref>Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.</ref> ''D. laevigatum'' has been recorded as a food source for white-tailed deer as well as northern bobwhite quail.<ref>Atwood, E. L. (1941). "White-tailed deer foods of the United States." The Journal of Wildlife Management 5(3): 314-332.</ref><ref>Hamrick, R., et al. (2007). Ecology & management of northern bobwhite. Publication 2179. Mississippi State, MS, Mississippi State University [Extension Service of Mississippi State University, cooperating with U.S. Department of Agriculture].</ref> | ||

<!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | <!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | ||

Revision as of 14:03, 22 June 2022

| Desmodium laevigatum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae ⁄ Leguminosae |

| Genus: | Desmodium |

| Species: | D. laevigatum |

| Binomial name | |

| Desmodium laevigatum (Nutt.) DC. | |

| |

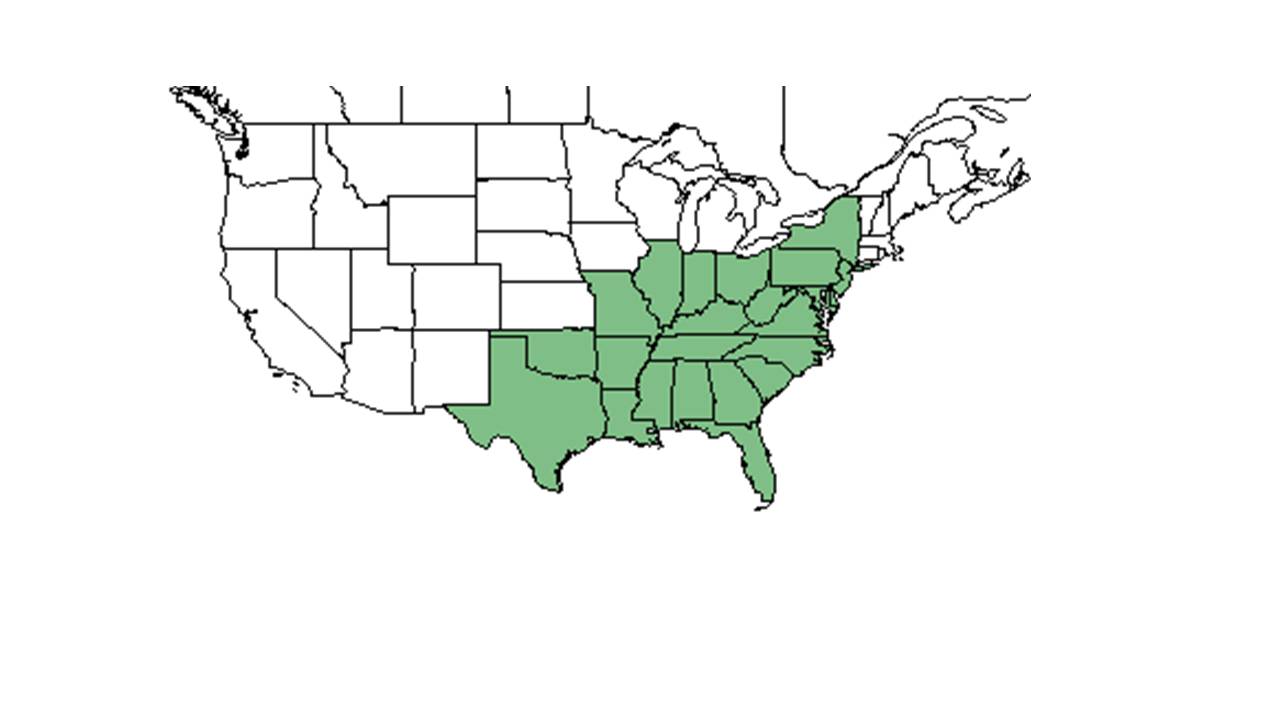

| Natural range of Desmodium laevigatum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Smooth Tick-trefoil

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonym: Meibomia laevigata (Nuttall) Kuntze.[1]

Varieties: none.[1]

Description

Generally for the Desmodium genus, they are "annual or perennial herbs, shrubs or small trees. Leaves 1-5 foliolate, pinnately 3-foliolate in ours or rarely the uppermost or lowermost 1-foliolate; leaflets entire, usually stipellate; stipules caduceus to persistent, ovate to subulate, foliaceous to setaceous, often striate. Inflorescence terminal and from the upper axils, paniculate or occasionally racemose; pedicel of each papilionaceous flower subtended by a secondary bract or bractlet, the cluster of 1-few flowers subtended by a primary bract. Calyx slightly to conspicuously 2-lipped, the upper lip scarcely bifid, the lower lip 3-dentate; petals pink, roseate, purple, bluish or white; stamens monadelphous or more commonly diadelphous and then 9 and 1. Legume a stipitate loment, the segments 2-many or rarely solitary, usually flattened and densely uncinated-pubescent, separating into 1-seeded, indehiscent segments." [2]

Specifically, for D. laevigatum species, they are "erect perennial; stems 0.5-1.2 m tall, glabrous to sparsely and inconspicuously uncinulate-puberulent. Terminal leaflets ovate to elliptic-ovate or elliptic-oblong, (3) 4-7 (9) cm long, glabrous to very sparsely puberulent above, glabrous to puberulent or sparsely short-pilose, often glaucous beneath with the trichomes largely restricted to the principal veins; stipules caduceus, lance-attenuate, 5-8 mm long; stipels persistent. Inflorescence usually paniculate, moderately to densely uncinulate-puberulent; pedicels mostly 7-19 mm long. Calyx densely puberulent; petals pink or roseate to purple, 8-10 mm long; stamens diadelphous. Loment of 2-5 subrhombic segments, each about 5-8 mm long, 3.5-5 mm broad, with a straight or slightly convex upper suture and an abruptly angled lower suture, with densely uncinulate sutures; stipe ca. 4.5-6.5 mm longer, much longer than the calyx tube but often equaling or even exceeding the calyx lobes, shorter than stamina remnants." [2]

Distribution

D. laevigatum is native to the United States from south New York west to Indiana and Missouri, south to north Florida and the panhandle, and west to Texas.[3]

Ecology

Habitat

This species is commonly found in fields, woodland borders, pine and dry oak forests, and disturbed areas in its native distribution.[3] It has been observed in areas that frequently burn such as open woods bordering a bay, hardwood hammocks, upland pine, in open mixed pine-hardwood forest, well drained upland, savannas, turkey oak sand ridges. Requires low-high light levels. Is associated with loamy sand, sandy clay loam, limestone, and sand soil types.[4] Where it is found, it is infrequent compared to other Desmodium species that can be found in the same habitat.[5] D. laevigatum has been found to respond positively to disturbance, where a study found flowering to increase in response to tornado damage and in turn an increase in light.[6] D. laevigatum was found to increase in occurrence and abundance in response to clearcutting and chopping in South Carolina. It has shown regrowth in reestablished native forest habitat that was disturbed by these practices.[7]

Associated species include Desmodium ciliare, D. lineatum, D. glabellum.[4]

Phenology

D. laevigatum commonly flowers between June and September and fruits between August and October.[3] It has been observed flowering from September to November with peak inflorescence in September; it is also been observed fruiting during the same time period.[8][4]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by translocation on animal fur or feathers. [9]

Fire ecology

Populations of Desmodium laevigatum have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[10][11] It has been observed in areas that are frequently burned[4], but has also been found in areas that are fire excluded which means it is not fully fire dependent.[12] For fire seasonality, one study found greatest abundance after a summer burn rather than a spring burn.[13]

Herbivory and toxicology

Desmodium laevigatum consists of approximately 10-25% of the diet for large mammals and terrestrial birds.[14] D. laevigatum has been recorded as a food source for white-tailed deer as well as northern bobwhite quail.[15][16]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

D. laevigatum is listed as endangered by the New York Department of Environmental Conservation, Division of Land and Forests.[17]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 604-11. Print.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, R.K. Godfrey, Angus Gholson, A. F. Clewell, V. Sullivan, J. Wooten, R. Kral, R. Komarek, T. MacClendon, - Boothes, Travis MacClendon, Karen MacClendon, Geo. Wilder, Harry E. Ahles, C. R. Bell, H. R. Reed, Delzie Demaree, William B. Fox, and S. G. Boyce. States and Counties: Alabama: Etowah, Franklin, and Lee. Arkansas: Drew. Florida: Bay, Calhoun, Franklin, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Liberty, Okaloosa,and Wakulla. Georgia: Baker, Decatur, Grady,and Thomas. Mississippi: Pearl River. North Carolina: Sampson. South Carolina: Beaufort. Virginia: Montgomery.

- ↑ Hainds, M. J., et al. (1999). "Distribution of native legumes (Leguminoseae) in frequently burned longleaf pine (Pinaceae)-wiregrass (Poaceae) ecosystems." American Journal of Botany 86: 1606-1614.

- ↑ Brewer, S. J., et al. (2012). "Do natural disturbances or the forestry practices that follow them convert forests to early-successional communities?" Ecological Applications 22: 442-458.

- ↑ Cushwa, C.T. and M.B. Jones. (1969). Wildlife Food Plants on Chopped Areas in Piedmont South Carolina. Note SE-119. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station. 4 pp.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 26 APR 2019

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Clewell, A. F. (2014). "Forest development 44 years after fire exclusion in formerly annually burned oldfield pine woodland, Florida." Castanea 79: 147-167.

- ↑ Cushwa, C. T., et al. (1970). Response of legumes to prescribed burns in loblolly pine stands of the South Carolina Piedmont. Asheville, NC, USDA Forest Service, Research Note SE-140: 6.

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Atwood, E. L. (1941). "White-tailed deer foods of the United States." The Journal of Wildlife Management 5(3): 314-332.

- ↑ Hamrick, R., et al. (2007). Ecology & management of northern bobwhite. Publication 2179. Mississippi State, MS, Mississippi State University [Extension Service of Mississippi State University, cooperating with U.S. Department of Agriculture].

- ↑ USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 26 April 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.