Difference between revisions of "Pinus taeda"

(→Conservation, cultivation, and restoration) |

|||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

Seeds of ''P. taeda'' have low viability after one year.<ref>Kirkman, L. K. and R. R. Sharitz (1994). Vegetation disturbance and maintenance of diversity in intermittently flooded Carolina bays in South Carolina. Ecological Applications 4: 177-188.</ref> | Seeds of ''P. taeda'' have low viability after one year.<ref>Kirkman, L. K. and R. R. Sharitz (1994). Vegetation disturbance and maintenance of diversity in intermittently flooded Carolina bays in South Carolina. Ecological Applications 4: 177-188.</ref> | ||

===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ||

| − | ''P. taeda'' is fire resistant and has a high fire tolerance | + | ''P. taeda'' is fire resistant and has a high fire tolerance<ref name= "USDA Plant Database"/> as evidenced by populations known to persist through repeated annual burning.<ref>Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.</ref> |

| + | |||

===Pollination and use by animals=== | ===Pollination and use by animals=== | ||

''Pinus taeda'' has been observed to host leafcutting bees such as ''Spissistilus festinus'' (family Membracidae), swallowtail butterflys such as ''Graphium sp.'' (family Papilionidae), aphids from the Aphididae family such as ''Cinara sp.'' and ''Uroleucon sp.'', assassin bugs from the Reduviidae family such as ''Apiomerus crassipes'', ''Rhynocoris sp.'' and ''Zelus tetracanthus'', and plant bugs from the Miridae family such as ''Phoenicocoris claricornis'' and ''Pilophorus laetus''.<ref>Discoverlife.org [https://www.discoverlife.org/20/q?search=Bidens+albaDiscoverlife.org|Discoverlife.org]</ref> | ''Pinus taeda'' has been observed to host leafcutting bees such as ''Spissistilus festinus'' (family Membracidae), swallowtail butterflys such as ''Graphium sp.'' (family Papilionidae), aphids from the Aphididae family such as ''Cinara sp.'' and ''Uroleucon sp.'', assassin bugs from the Reduviidae family such as ''Apiomerus crassipes'', ''Rhynocoris sp.'' and ''Zelus tetracanthus'', and plant bugs from the Miridae family such as ''Phoenicocoris claricornis'' and ''Pilophorus laetus''.<ref>Discoverlife.org [https://www.discoverlife.org/20/q?search=Bidens+albaDiscoverlife.org|Discoverlife.org]</ref> | ||

Revision as of 19:40, 22 July 2021

Common name: loblolly pine [1], old field pine [1]

| Pinus taeda | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John Gwaltney hosted at Southeastern Flora.com | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Pinales |

| Family: | Pinaceae |

| Genus: | Pinus |

| Species: | P. taeda |

| Binomial name | |

| Pinus taeda L. | |

| |

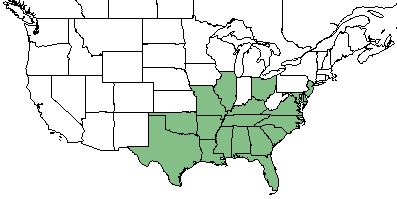

| Natural range of Pinus taeda from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: none

Varieties: none

Description

P. taeda is a perennial tree of the Pinaceae family native to North America.[2]

Distribution

P. taeda is found in the southeastern corner of the United States excluding Indiana and West Virginia.[2]

Ecology

Habitat

P. taeda proliferates in forests, fields, and pine plantations.[1] Specimens have been collected from palm hammock ear edge of river, open pine woodland, small old field, mesic coastal palm oak hammock, loamy soil near small pond, palmetto flatwoods, open pasture, mixed hardwoods, and pine flatwoods.[3]

P. taeda became absent in response to military training in west Georgia longleaf pine forests. It has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished pine forests that were disturbed by this activity.[4]

Pinus taeda is frequent and abundant in the Peninsula Xeric Sandhills, North Florida Longleaf Woodlands, North Florida Subxeric Sandhills, Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands, and Upper Panhandle Savannas community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[5]

Phenology

P. taeda has been observed flowering in March.[6]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by wind.[7]

Seed bank and germination

Seeds of P. taeda have low viability after one year.[8]

Fire ecology

P. taeda is fire resistant and has a high fire tolerance[2] as evidenced by populations known to persist through repeated annual burning.[9]

Pollination and use by animals

Pinus taeda has been observed to host leafcutting bees such as Spissistilus festinus (family Membracidae), swallowtail butterflys such as Graphium sp. (family Papilionidae), aphids from the Aphididae family such as Cinara sp. and Uroleucon sp., assassin bugs from the Reduviidae family such as Apiomerus crassipes, Rhynocoris sp. and Zelus tetracanthus, and plant bugs from the Miridae family such as Phoenicocoris claricornis and Pilophorus laetus.[10]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

P. taeda is listed as a weedy or invasive species by the Hawaiian Ecosystems at Risk Project Biological Resources Division.[2] This species should avoid soil disturbance by military training to conserve its presence in pine communities.[4]

Cultural use

Tar from these trees can be used as inhalants for treating pulmonary diseases. Salves and oils could be used for acne and skin diseases, intestinal worms, as a stimulant, and as a laxative.

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 USDA Plant Database https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=PITA

- ↑ URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, R.K. Godfrey, Angus Gholson, Gary Knight, S.W. Leonard, Patricia Elliot, K. Craddock Burks, k. Studenroth, C. Florke, A.G. Shuey, J. Poppleton, D.B. Ward, S.S. Ward, T. Myint, P. Cmanor, S.Snedaker, Kurt Blum, J.M. Kane, T. MacClendon, K. MacClendon. States and counties: Florida (Franklin, Leon, Wakulla, Taylor, Gadsden, Leon, Jackson, Orange, Liberty, Levy, Jefferson, Lake, Escambia, Hamilton, St. Johns, Washington, Calhoun) Georgia (Thomas)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 24 MAY 2018

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. K. and R. R. Sharitz (1994). Vegetation disturbance and maintenance of diversity in intermittently flooded Carolina bays in South Carolina. Ecological Applications 4: 177-188.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]