Difference between revisions of "Cephalanthus occidentalis"

(→Ecology) |

|||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

Intense fires will decrease the response of regrowth, though the ''C.. occidentalis'' can resprout after lower intensity burns. <ref name= "USDA"> [https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=CEAM USDA Plant Database]</ref> | Intense fires will decrease the response of regrowth, though the ''C.. occidentalis'' can resprout after lower intensity burns. <ref name= "USDA"> [https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=CEAM USDA Plant Database]</ref> | ||

| − | ===Pollination=== | + | ===Pollination and use by animals=== |

| − | The nectar of ''C. occidentalis'' attracts butterflies, bees, and hummingbirds; bees utilize this nectar to make honey.<ref name= "Wennerberg"/> Species from the Syrphidae and Tachinidae (Diptera) fly families were collected on the plant as possible pollinators.<ref name= "Tooker">Tooker, J. F., et al. (2006). "Floral host plants of Syrphidae and Tachinidae (Diptera) of central Illinois." Annals of the Entomological Society of America 99(1): 96-112.</ref> | + | The nectar of ''C. occidentalis'' attracts butterflies, bees, and hummingbirds; bees utilize this nectar to make honey.<ref name= "Wennerberg"/> Species from the Syrphidae and Tachinidae (Diptera) fly families were collected on the plant as possible pollinators.<ref name= "Tooker">Tooker, J. F., et al. (2006). "Floral host plants of Syrphidae and Tachinidae (Diptera) of central Illinois." Annals of the Entomological Society of America 99(1): 96-112.</ref> This species is also visited by butterflies from the Lycaenidae family (''Calycopis cecrops''), bees from the Apidea family (''Bombus perplexus''), sweat bees from the Halictidea family (''Agapostemon splendens''), leafcutting bees from the Megachilidae family (''Megachile albitarsis, M. mendica'' and ''M. xylocopoides'').<ref>Discoverlife.org [https://www.discoverlife.org/20/q?search=Bidens+albaDiscoverlife.org|Discoverlife.org]</ref> Additionally, this species hosts aphids from the Aphididae family (''Aphis sp.''), planthoppers from the Dictyopharidae family (''Rhynchomitra microrhina''), plant bugs from the Miridae family (''Lygus lineolaris'') and stink bugs from the Pentatomidae family (''Euschistus servus'').<ref>Discoverlife.org [https://www.discoverlife.org/20/q?search=Bidens+albaDiscoverlife.org|Discoverlife.org]</ref> |

| − | |||

The seeds of ''C. occidentalis'' are eaten by shorebirds and waterfowl, while white-tailed deer browse the foliage. Wood ducks utilize the plant's structure for cover and protection for their brooding nests.<ref name= "Wennerberg"/> It is an adult food source for some Lepidoptera including the titan sphinx (''Aellopos titan'') and the hydrangea sphinx (''Darapsa versicolor'').<ref name= "lady bird"/> | The seeds of ''C. occidentalis'' are eaten by shorebirds and waterfowl, while white-tailed deer browse the foliage. Wood ducks utilize the plant's structure for cover and protection for their brooding nests.<ref name= "Wennerberg"/> It is an adult food source for some Lepidoptera including the titan sphinx (''Aellopos titan'') and the hydrangea sphinx (''Darapsa versicolor'').<ref name= "lady bird"/> | ||

<!--==Diseases and parasites==--> | <!--==Diseases and parasites==--> | ||

Revision as of 14:07, 23 June 2021

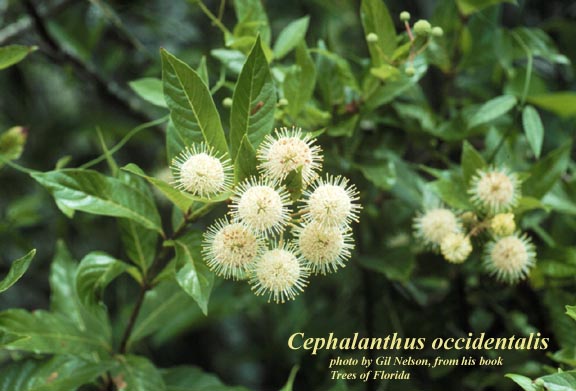

Common Names: Common Buttonbush [1], Globeflower. [2]

| Cephalanthus occidentalis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by the Atlas of Florida Plants Database | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Rubiales |

| Family: | Rubiaceae |

| Genus: | Cephalanthus |

| Species: | C. occidentalis |

| Binomial name | |

| Cephalanthus occidentalis L. | |

| |

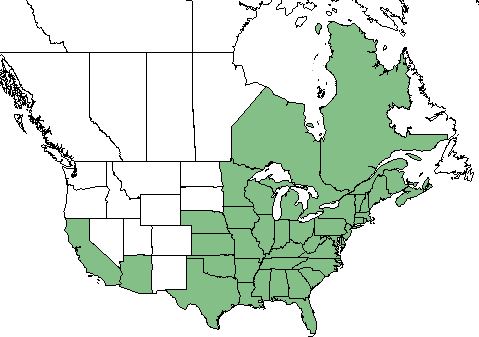

| Natural range of Cephalanthus occidentalis from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: none.[3]

Varieties: none.[3]

Description

C. occidentalis is a perennial shrub/tree of the Rubiaceae family native to North America.[1] It contains the poison cephalathin, which induces vomiting, convulsions, and paralysis if ingested. This shrub reaches heights of 6 meters, is multi-stemmed, and stem bases are swollen. Twigs are green when young, have elongated lenticels, 4-sided, and brown and scaly when mature. Leaves whorled or oppositely arranged, glossy in appearance and dark green, developing in May. Flowers tube-shaped, 4 or 5-lobed, reddish to white in color, and develop in dense clusters at branch ends; the long styles on the flower give the pincushion like appearance. Fruit ball-shaped with 2-seeded nutlets enclosed. It can easily be identified by the flower heads, elongated lenticels, or swollen stem bases.[4]

Distribution

C. occidentalis is found in the eastern United States, California and Arizona, as well as eastern Canada. It is also native to Mexico.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

C. occidentalis habitat is primarily wetlands. It can be found on streambanks, depressional wetlands, lakes, and in other standing water.[5] This shrub requires full sunlight for flowering and can withstand habitats of up to three feet of standing water.[1] It has also been observed in salt marshes, oak ravines, swamps and woodlands, cypress ponds, wet hammocks, edges of ponds and creeks, and wet disturbed areas.[6] Soils it can grow on include sandy, sandy loam, limestone-based, medium loam, clay, and clay loam.[7]

Associated species: Fagus grandifolia, Acer rubrum, Acer saccharum, Quercus velutina, Quercus palustris, Nyssa sp., Taxodium distichum, Taxodium sp., Myrica caroliniensis, Myrica cerifera, Persea borbonia, Ilex sp., Vitis sp., Viburnum sp., Toxicodendron radicans, Sorghastrum nutans, Andropogon gerardi, Panicum sp., Juncus sp., Osmunda sp., Pinus clausa, Pinus strobus, Rosa palustris, and Thuja occidentalis.[4][6]

Phenology

C. occidentalis has been observed to flower April through October with peak inflorescence in June; flowering ranging in color of white to pink.[7][8]

Seed dispersal

It is thought to be dispersed by wind, and may also secondarily be dispersed by water.[9]

Seed bank and germination

Seeds of the C. occidentalis need to be germinated in moist soil under full sun or slight shade.[1] On study found seeds in the seed bank to persist deeper in the soil in larger numbers.[10]

Fire ecology

Intense fires will decrease the response of regrowth, though the C.. occidentalis can resprout after lower intensity burns. [1]

Pollination and use by animals

The nectar of C. occidentalis attracts butterflies, bees, and hummingbirds; bees utilize this nectar to make honey.[4] Species from the Syrphidae and Tachinidae (Diptera) fly families were collected on the plant as possible pollinators.[11] This species is also visited by butterflies from the Lycaenidae family (Calycopis cecrops), bees from the Apidea family (Bombus perplexus), sweat bees from the Halictidea family (Agapostemon splendens), leafcutting bees from the Megachilidae family (Megachile albitarsis, M. mendica and M. xylocopoides).[12] Additionally, this species hosts aphids from the Aphididae family (Aphis sp.), planthoppers from the Dictyopharidae family (Rhynchomitra microrhina), plant bugs from the Miridae family (Lygus lineolaris) and stink bugs from the Pentatomidae family (Euschistus servus).[13]

The seeds of C. occidentalis are eaten by shorebirds and waterfowl, while white-tailed deer browse the foliage. Wood ducks utilize the plant's structure for cover and protection for their brooding nests.[4] It is an adult food source for some Lepidoptera including the titan sphinx (Aellopos titan) and the hydrangea sphinx (Darapsa versicolor).[7]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Herbicides can be detrimental to the species, and springtime flooding can damage it as well.[4] However, a slow release fertilizer can be used for enhancing seed production and flowering.[14] Pruning the plant is not needed for its spread, but can be used in the spring to fix overall shape. When water levels are low, dense shrubs in the fall can be cut back to maintain them.[4] A cultivar available is 'Keystone', which was released by the Big Flats New York Plant Materials Center.[14] For restoration, C. occidentalis can be used for erosion control on shorelines. It has a strong base that can stabilize the plant and the shoreline. [1]

Cultural use

Historically, Native American tribes used this plant medicinally in multiple ways. The bark was deconcocted to be used for washes of sore eyes, anti-inflammation and rheumatism medications, antidiarrheal agents, relief for headaches and fevers, skin astringents, and venereal disease remedies. As well, the bark was chewed to help alleviate toothaches, and the roots were utilized for blood medicine and muscle inflammation.[4] It was also generally used medicinally by physicians as an aperient and laxative, a febrifuge, and a tonic.[15]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 USDA Plant Database

- ↑ Gee, K. L., et al. (1994). White-tailed deer: their foods and management in the cross timbers. Ardmore, OK, Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Wennerberg, S. (2006). Plant Guide: Common Buttonbush Cephalanthus occidentalis. N.R.C.S. United States Department of Agriculture. Baton Rouge, LA.

- ↑ Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: March 2019. Collectors: Harry E. Ahles, Loran C. Anderson, Raymond Athey, Tom Barnes, F. Barrington, Elizabeth Ann Bartholomew, J. Beckner, K. E. Blum, John R. Bozeman, Kathy Craddock Burks, Andre F. Clewell, Delzie Demaree, R. F. Doren, J. A. Duke, Elaine Dunkleberger, Wm. H. Ellis, Joseph Ewan, Paul Fortsch, P. Garton, James P. Gillespie, Robert K. Godfrey, N. C. Henderson, B. K. Holst, R. D. Houlk, S. B. Jones, Ed Keppner, Lisa Keppner, Gary R. Knight, R. Komarek, Kral, Robert Kral, James Lackey, Alex Lasseigne, J. Lazor, R. Lazor, E Lehto, Robert J. Lemaire, William Lindsey, S. J. Lombardo, K. M. Meyer, Mitchell, Richard S. Mitchell, J. Richard Moore, M. Nee, Robert A. Norris, Sara J. Noyes, John C. Ogden, A. Quagliata, S. J. R., A. E. Radford, G. S. Ramseur, Gwynn W. Ramsey, P. L. Redfearn, Jr., Ann M. Redmond, Clyde F. Reed, William Reese, Raul Rivero, Fr. Edmond Roy, Cecil R. Slaughter, T. E. Smith, Margaret De Sousa, William R. Stimson, Donald E. Stone, James Teer, John W. Thieret, David W. Thompson, Robert F. Thorne, A. Townesmith, D. B. Ward, S. S. Ward, Mary E. Wharton, Rodie White, Eula Whitehouse, R. L. Wilbur, N. Williams, Roomie Wilson, D. R. Windler, and Jean W. Wooten. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Broward, Clay, Collier, Columbia, Dixie, Franklin, Gadsden, Gulf, Hernando, Jackson, Jefferson, Lafayette, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Marion, Pasco, Polk, Putnam, Sarasota, Seminole, St Johns, Taylor, Wakulla, Walton, and Washington. Georgia: Colquitt, Grady, and Thomas. Alabama: Geneva and Wilcox. Arizona: Maricopa. Arkansas: Clark, Washington, and White. California: Lake. Indiana: Cass. Kansas: Lyon. Kentucky: Todd. Louisiana: Evangeline, Grant, Lafayette, Livingston, St Landry, St Tammany, and Tangipahoa. Maryland: Cecil. Michigan: Bath and Cheboygan. Mississippi: Harrison, Jasper, Jones, and Leake. Missouri: Howell and Platte. New Jersey: Patrick. New York: Yates. North Carolina: Davie, Edgecombe, Granville, Northampton, and Washington. Oklahoma: Comanche. Tennessee: Davidson and Knox. Texas: Freestone, Reeves, and Taylor. Virginia: Augusta, Halifax, and Montgomery. West Virginia: Wirt. Wisconsin: Richland.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: April 4, 2019

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 4 APR 2019

- ↑ Battaglia, L. L., et al. (2002). "Sixteen years of old-field succession and reestablishment of a bottomland hardwood forest in the lower Mississippi alluvial valley." Wetlands 22(1): 1-17.

- ↑ Leck, M. A. and R. L. Simpson (1987). "Seed bank of a freshwater tidal wetland: Turnover and relationship to vegetation change." American Journal of Botany 74(3): 360-370.

- ↑ Tooker, J. F., et al. (2006). "Floral host plants of Syrphidae and Tachinidae (Diptera) of central Illinois." Annals of the Entomological Society of America 99(1): 96-112.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [2]

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [3]

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 USDA NRCS Northeast Plant Materials Program. (2006). Plant Fact Sheet: Common buttonbush Cephalanthus occidentalis. N.R.C.S. United States Department of Agriculture.

- ↑ Nickell, J. M. (1911). J.M.Nickell's botanical ready reference : especially designed for druggists and physicians : containing all of the botanical drugs known up to the present time, giving their medical properties, and all of their botanical, common, pharmacopoeal and German common (in German) names. Chicago, IL, Murray & Nickell MFG. Co.