Difference between revisions of "Sporobolus junceus"

(→Ecology) |

|||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ||

| − | ''S. junceus'' has been found in open pinelands, scrub barrens, longleaf pine-saw palmetto flatwoods, pine barrens, calcareous glades, pine-wiregrass woods, open oak woods, turkey oak flatwoods, and deciduous oak ridges.<ref name="FSU"> Florida State University Herbarium Database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: George R. Cooley, A. H. Curtiss, Richard J. Eaton, Robert K. Godfrey, R. Kral, John B. Nelson, R. S. Mitchell, Gwynn W. Ramsey, and Allen G. Shuey. States and counties: Florida: Bay, Calhoun, Duval, Gadsden, Levy, Manatee, and Suwannee.</ref> It is also found in disturbed areas including burned pinelands and logged/cattle-grazed pinelands | + | ''S. junceus'' has been found in open pinelands, scrub barrens, longleaf pine-saw palmetto flatwoods, pine barrens, calcareous glades, pine-wiregrass woods, open oak woods, turkey oak flatwoods, and deciduous oak ridges.<ref name="FSU"> Florida State University Herbarium Database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: George R. Cooley, A. H. Curtiss, Richard J. Eaton, Robert K. Godfrey, R. Kral, John B. Nelson, R. S. Mitchell, Gwynn W. Ramsey, and Allen G. Shuey. States and counties: Florida: Bay, Calhoun, Duval, Gadsden, Levy, Manatee, and Suwannee.</ref> It is also found in disturbed areas including burned pinelands and logged/cattle-grazed pinelands<ref name="FSU"/> and is frequent and abundant in the Peninsula Xeric Sandhills, Panhandle Xeric Sandhills, North Florida Subxeric Sandhills community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).<ref>Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.</ref> |

| − | ''S. junceus'' can become one of the more dominant grasses.<ref name="Shepherd et al 2012"/> It appears to be rather shade tolerant since its coverage is not correlated with longleaf pine stand density.<ref name="Harrington 2006">Harrington T. B. (2006). Plant competition, facilitation, and other overstorey-understory interactions in longleaf pine ecosystems. In: Jose S., Jokela E. J., and Miller D. L. (eds) The longleaf pine ecosystem: ecology, silviculture, and restoration. Springer, New York, pp. 135-156.</ref> | + | ''S. junceus'' can become one of the more dominant grasses.<ref name="Shepherd et al 2012"/> It appears to be rather shade tolerant since its coverage is not correlated with longleaf pine stand density.<ref name="Harrington 2006">Harrington T. B. (2006). Plant competition, facilitation, and other overstorey-understory interactions in longleaf pine ecosystems. In: Jose S., Jokela E. J., and Miller D. L. (eds) The longleaf pine ecosystem: ecology, silviculture, and restoration. Springer, New York, pp. 135-156.</ref> ''S. junceus'' responds negatively to soil disturbance by agriculture in South Carolina's traditionally longleaf communities.<ref>Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.</ref> It also responds negatively to agricultural-based soil disturbance in South Carolina coastal plain communities. This marks it as a possible indicator species for remnant woodland.<ref>Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.</ref> ''S. junceus'' responds negatively to soil disturbance by agriculture in Southwest Georgia.<ref>Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.</ref> It also responds negatively or not at all to soil disturbance by roller chopping in South Florida.<ref>Lewis, C.E. (1970). Responses to Chopping and Rock Phosphate on South Florida Ranges. Journal of Range Management 23(4):276-282.</ref> It does not respond to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.<ref>Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.</ref> |

| − | '' | + | Associated species: ''Phoebanthus, Liatris,'' and ''Chrysopsis''.<ref name="FSU"/> |

| − | |||

| − | '' | ||

===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ||

| Line 49: | Line 47: | ||

===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ||

Burns during April, May, and July yielded larger numbers of flowers than burns at other times of the year in a Florida sandhill longleaf pine community.<ref name="Shepherd et al 2012">Shepherd B. J., Miller D. L., and Thetford M. (2012). Fire season effects on flowering characteristics and germination of longleaf pine (''Pinus palustris'') savanna grasses. Restoration Ecology 20(2):268-276.</ref><ref name="Canfield & Tanner 1997">Canfield S. L. and Tanner G. W. (1997). Observations of pineywoods dropseed (''Sporobolus junceus'') phenological development following fire in a sandhill community. Florida Scientist 60(2):69-72</ref> After a May burn in north Florida, inflorescence and mature seeds were produced within 7-9 weeks following the fire.<ref name="Canfield & Tanner 1997"/> Despite affecting flowering and seeds, an Alabama study in 2004 and 2005 showed no difference in stem densities between burned and unburned glades. These densities ranged from 1.5 to 3.4 stems m<sup>-2</sup>.<ref name="Duncan et al 2008">Duncan R. S., Anderson C. B., Sellers H. N., Robbins E. E. (2008). The effect of fire reintroduction on endemic and rare plants of a southeastern glade ecosystem. Restoration Ecology 16(1):39-49.</ref> | Burns during April, May, and July yielded larger numbers of flowers than burns at other times of the year in a Florida sandhill longleaf pine community.<ref name="Shepherd et al 2012">Shepherd B. J., Miller D. L., and Thetford M. (2012). Fire season effects on flowering characteristics and germination of longleaf pine (''Pinus palustris'') savanna grasses. Restoration Ecology 20(2):268-276.</ref><ref name="Canfield & Tanner 1997">Canfield S. L. and Tanner G. W. (1997). Observations of pineywoods dropseed (''Sporobolus junceus'') phenological development following fire in a sandhill community. Florida Scientist 60(2):69-72</ref> After a May burn in north Florida, inflorescence and mature seeds were produced within 7-9 weeks following the fire.<ref name="Canfield & Tanner 1997"/> Despite affecting flowering and seeds, an Alabama study in 2004 and 2005 showed no difference in stem densities between burned and unburned glades. These densities ranged from 1.5 to 3.4 stems m<sup>-2</sup>.<ref name="Duncan et al 2008">Duncan R. S., Anderson C. B., Sellers H. N., Robbins E. E. (2008). The effect of fire reintroduction on endemic and rare plants of a southeastern glade ecosystem. Restoration Ecology 16(1):39-49.</ref> | ||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ===Pollination and use by animals=== <!--Herbivory, granivory, insect hosting, etc.--> |

''S. junceus'' provides 2-5% of the diet of some terrestrial birds.<ref name="USDA"/> | ''S. junceus'' provides 2-5% of the diet of some terrestrial birds.<ref name="USDA"/> | ||

<!--==Diseases and parasites==--> | <!--==Diseases and parasites==--> | ||

Revision as of 14:35, 18 June 2021

| Sporobolus junceus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by James H. Miller, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org hosted at Forestryimages.org | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida - Moncots |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Cyperaceae |

| Genus: | Sporobolus |

| Species: | S. junceus |

| Binomial name | |

| Sporobolus junceus (P. Beauv.) Kunth | |

| |

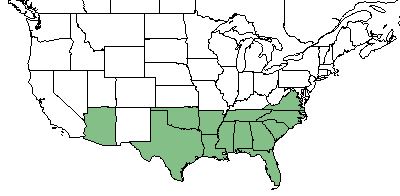

| Natural range of Sporobolus junceus from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name(s): sandhills dropseed,[1] pineywoods dropseed[2]

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonym(s): S. gracilis (Trinius) Merrill

Description

Sporobolus junceus is a monoecious perennial graminoid.[2]

Sporobolus junceus does not have specialized underground storage units apart from its fibrous roots.[3] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have a water content of 39.5% (ranking 94 out of 100 species studied).[3]

Distribution

This species is found in southeastern Virginia, south to Florida and westward to southeastern Oklahoma and Texas.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

S. junceus has been found in open pinelands, scrub barrens, longleaf pine-saw palmetto flatwoods, pine barrens, calcareous glades, pine-wiregrass woods, open oak woods, turkey oak flatwoods, and deciduous oak ridges.[4] It is also found in disturbed areas including burned pinelands and logged/cattle-grazed pinelands[4] and is frequent and abundant in the Peninsula Xeric Sandhills, Panhandle Xeric Sandhills, North Florida Subxeric Sandhills community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[5]

S. junceus can become one of the more dominant grasses.[6] It appears to be rather shade tolerant since its coverage is not correlated with longleaf pine stand density.[7] S. junceus responds negatively to soil disturbance by agriculture in South Carolina's traditionally longleaf communities.[8] It also responds negatively to agricultural-based soil disturbance in South Carolina coastal plain communities. This marks it as a possible indicator species for remnant woodland.[9] S. junceus responds negatively to soil disturbance by agriculture in Southwest Georgia.[10] It also responds negatively or not at all to soil disturbance by roller chopping in South Florida.[11] It does not respond to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.[12]

Associated species: Phoebanthus, Liatris, and Chrysopsis.[4]

Phenology

S. junceus has been observed to flower from September through November with peak inflorescence in October,[1][13], although there are reports of flowering occurring between March and June as well.[13]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity. [14]

Fire ecology

Burns during April, May, and July yielded larger numbers of flowers than burns at other times of the year in a Florida sandhill longleaf pine community.[6][15] After a May burn in north Florida, inflorescence and mature seeds were produced within 7-9 weeks following the fire.[15] Despite affecting flowering and seeds, an Alabama study in 2004 and 2005 showed no difference in stem densities between burned and unburned glades. These densities ranged from 1.5 to 3.4 stems m-2.[16]

Pollination and use by animals

S. junceus provides 2-5% of the diet of some terrestrial birds.[2]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

On a central Florida sandhill, S. junceus planted in the winter established very well on overburned soils and produced the highest densities (up to 10 plants m-1 of the plants tested.[17] Seeds can be hand collected and mixed with others (e.g. wiregrass) for sowing on restoration sites.[18]

Cultural use

In the past, native peoples would harvest the tiny husk-less grains and grind them into a flour.[19]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Weakley A. S.(2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 8 January 2018). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Florida State University Herbarium Database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: George R. Cooley, A. H. Curtiss, Richard J. Eaton, Robert K. Godfrey, R. Kral, John B. Nelson, R. S. Mitchell, Gwynn W. Ramsey, and Allen G. Shuey. States and counties: Florida: Bay, Calhoun, Duval, Gadsden, Levy, Manatee, and Suwannee.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Shepherd B. J., Miller D. L., and Thetford M. (2012). Fire season effects on flowering characteristics and germination of longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) savanna grasses. Restoration Ecology 20(2):268-276.

- ↑ Harrington T. B. (2006). Plant competition, facilitation, and other overstorey-understory interactions in longleaf pine ecosystems. In: Jose S., Jokela E. J., and Miller D. L. (eds) The longleaf pine ecosystem: ecology, silviculture, and restoration. Springer, New York, pp. 135-156.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.

- ↑ Lewis, C.E. (1970). Responses to Chopping and Rock Phosphate on South Florida Ranges. Journal of Range Management 23(4):276-282.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 8 JAN 2018

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Canfield S. L. and Tanner G. W. (1997). Observations of pineywoods dropseed (Sporobolus junceus) phenological development following fire in a sandhill community. Florida Scientist 60(2):69-72

- ↑ Duncan R. S., Anderson C. B., Sellers H. N., Robbins E. E. (2008). The effect of fire reintroduction on endemic and rare plants of a southeastern glade ecosystem. Restoration Ecology 16(1):39-49.

- ↑ Pfaff S., Maura, Jr. C., and Gonter M. A. (2001). Performance of selected Florida native species on reclaimed phosphate minelands. #96-03-120R Brooksville, FL.

- ↑ Brockway D. G., Outcalt K. W., Tomczak D. J., and Johnson E. E. (2005) Restoration of Longleaf Pine Ecosystems. United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station, General Technical Report SRS-83.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.