Difference between revisions of "Desmodium strictum"

(→Description) |

|||

| Line 61: | Line 61: | ||

<!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | <!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | ||

| − | ==Conservation and | + | ==Conservation, cultivation, and restoration== |

''D. strictum'' is listed as endangered by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources.<ref>USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 26 April 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.</ref> | ''D. strictum'' is listed as endangered by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources.<ref>USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 26 April 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.</ref> | ||

| − | + | ==Cultural use== | |

| − | == | ||

==Photo Gallery== | ==Photo Gallery== | ||

<gallery widths=180px> | <gallery widths=180px> | ||

Revision as of 14:13, 8 June 2021

| Desmodium strictum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae ⁄ Leguminosae |

| Genus: | Desmodium |

| Species: | D. strictum |

| Binomial name | |

| Desmodium strictum (Pursh) DC. | |

| |

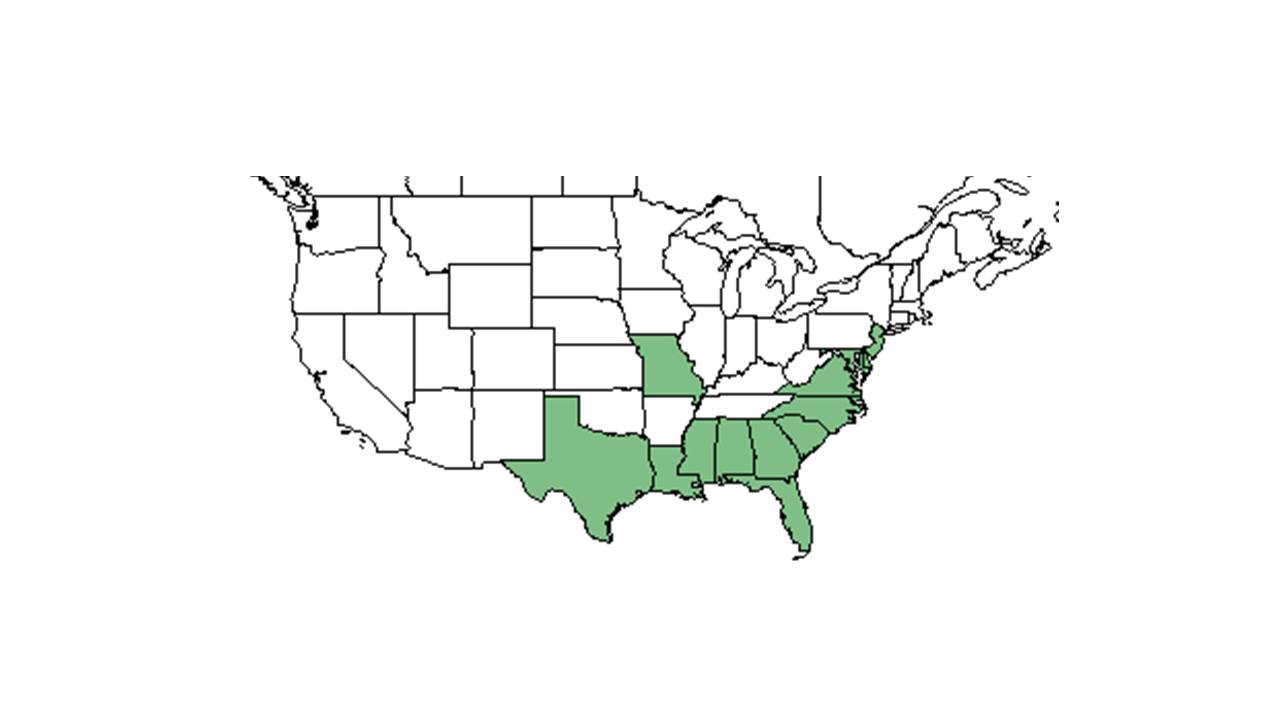

| Natural range of Desmodium strictum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Pine Barren Tick-trefoil; Pineland Tick-trefoil

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Meibomia stricta (Pursh) Kuntze.[1]

Varieties: none.[1]

Description

Generally, for Desmodium genus, they are "annual or perennial herbs, shrubs or small trees. Leaves 1-5 foliolate, pinnately 3-foliolate in ours or rarely the uppermost or lowermost 1-foliolate; leaflets entire, usually stipellate; stipules caduceus to persistent, ovate to subulate, foliaceous to setaceous, often striate. Inflorescence terminal and from the upper axils, paniculate or occasionally racemose; pedicel of each papilionaceous flower subtended by a secondary bract or bractlet, the cluster of 1-few flowers subtended by a primary bract. Calyx slightly to conspicuously 2-lipped, the upper lip scarcely bifid, the lower lip 3-dentate; petals pink, roseate, purple, bluish or white; stamens monadelphous or more commonly diadelphous and then 9 and 1. Legume a stipitate loment, the segments 2-many or rarely solitary, usually flattened and densely uncinated-pubescent, separating into 1-seeded, indehiscent segments." [2]

Specifically, for D.strictum species, they are "erect perennial; stems 0.5-1.2 m tall, sparsely to densely uncinulate-puberulent and short-pubescent, often becoming glabrate below. Terminal leaflets linear to narrowly oblong, often 6-10 X as long as wide, 3-7 cm long, glabrate or minutely puberulent or sparsely short-pubescent especially along the veins beneath, fine reticulate; stipules linear-subulate, 2-4 mm long; stipels persistent. Inflorescence usually paniculate, densely uncinulate-puberulent; pedicels (4) 6-11 mm long. Calyx densely puberulent and sparsely short-pubescent; petals purplish, 3-5 mm long, stamens diadelphous. Loments of 1-3 suborbicular to weakly obovate segments, each 4-6 mm long, 3-4 mm broad, upper suture of each segment slightly concave or indented, densely uncinlate-puberulent on both sutures and sides; stipe 1-2 mm long, about as long as calyx but shorter than stamina remnants." [2]

The root system of D.strictum includes stem tubers which store non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) important for both resprouting following fire and persisting during long periods of fire exclusion.[3] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an NSC concentration of 70.1 mg/g (ranking 62 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 48.8% (ranking 64 out of 100 species studied).[3]

Distribution

D. strictum is native to the United States from south New Jersey down to south Florida and west to western Louisiana.[4]

Ecology

Habitat

Generally, D. strictum can be found in dry woodlands and sandhills.[4] It thrives in open, frequently burned areas such as longleaf pine and shortleaf pine old field habitats (ultisols). [5] [6] It also occurs in longleaf pine-turkey oak sandhills (entisols), and in longleaf pine and slash pine flatwoods (spodosols).[6] It occurs in habitats dominated by ultisol soil types with average temperatures from 11 to 27° Celsuis, and with 132 cm of annual rainfall. [5] In florida, D. strictum is an indicator species of the clayhill longleaf woodlands community.[7] It is seen in habitats with soil types of sandy loam to eroded sandy clayey areas. [6] It prefers to grow in either partial shade or full shade.[8] Outside of the southeast coastal plain, D. strictum can be found in upland pitch pine barrens in New Jersey.[9] D. strictum responds positively to soil disturbance as observed from old field longleaf communities in South Carolina.[10] It also responds positively to soil disturbance by agriculture, indicating post-agricultural woodland.[11] D. strictum responds both positively and not at all to soil disturbance by roller chopping in Northwest Florida sandhills.[12]

Associated species include D. viridiflorum, D. floridanum, D. glabellum, D. canescens, D. marilandicum, Aristida stricta, Pinus palutris, and P. elliotii. [6]

Desmodium strictum is an indicator species for the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[13]

Phenology

D. strictum generally flowers from July through August and fruits from August through October.[4] It has been observed to flower from September to October with peak inflorescence in October, and fruit from September to November.[14][6]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by translocation on animal fur or feathers. [15]

Seed bank and germination

Because Desmodium strictum lacks a hard seed coat, is not capable of forming long-term persistent seed banks, and rather germinates readily within one year following dispersal.[5]

Fire ecology

It thrives in frequently burned (1-2 year interval) habitats.[5][6] Frequency of D. strictum is the greatest in response to winter and spring burn regiments rather than summer burn regiments.[16]

Use by animals

This species consists of approximately 10-25% of the diet for large mammals and terrestrial birds.[17]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

D. strictum is listed as endangered by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources.[18]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 604-9. Print.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Coffey, K. L. and L. K. Kirkman (2006). "Seed germination strategies of species with restoration potential in a fire-maintained pine savanna." Natural Areas Journal 26: 289-299.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: L. C. Anderson, R. K. Godfrey, V. Sullivan, J. Wooten, R. Kral, James R. Ray Jr., John Morrill, Robert L. Lazor, Andre F. Clewell, and T. MacClendon. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Bradford, Franklin, Gadsden, Hernando, Jackson, Leon, Putnam, Taylor, Wakulla, and Walton. Georgia: Baker, Grady, and Thomas.

- ↑ Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.

- ↑ [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: April 26, 2019

- ↑ [[2]] NatureServe Explorer. Accessed: April 26, 2019

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Hebb, E.A. (1971). Site Preparation Decreases Game Food Plants in Florida Sandhills. The Journal of Wildlife Management 35(1):155-162.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 26 APR 2019

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Kush, J. S., et al. (2000). Understory plant community response to season of burn in natural longleaf pine forests. Proceedings 21st Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference. Fire and forest ecology: innovative silviculture & vegetation management, Tallahassee, FL, Tall Timbers Research, Inc.

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 26 April 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.