Difference between revisions of "Desmodium rotundifolium"

Lsandstrum (talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ||

Generally, ''D. rotundifolium'' can be found in woodlands and dry forests.<ref name= "Weakley"/> As well, it has been observed to be found in mixed hardwoods, in lightly wooded hillsides, dry glacial drift, and open woods. It requires shaded areas, and is associated with drying sandy loam soil types.<ref name=fsu/> It is an upland species, and is not found in any wetlands or mesic habitats.<ref>Kirkman, L. K., et al. (1998). "Ecotone characterization between upland longleaf pine/wiregrass stands and seasonally-ponded isolated wetlands." Wetlands 18(3): 346-364.</ref> In Alabama, it is scattered throughout the state in open woodlands.<ref>Woods, M. (2008). "The genera Desmodium and Hylodesmum (Fabaceae) in Alabama." Castanea 73(1): 46-69.</ref> | Generally, ''D. rotundifolium'' can be found in woodlands and dry forests.<ref name= "Weakley"/> As well, it has been observed to be found in mixed hardwoods, in lightly wooded hillsides, dry glacial drift, and open woods. It requires shaded areas, and is associated with drying sandy loam soil types.<ref name=fsu/> It is an upland species, and is not found in any wetlands or mesic habitats.<ref>Kirkman, L. K., et al. (1998). "Ecotone characterization between upland longleaf pine/wiregrass stands and seasonally-ponded isolated wetlands." Wetlands 18(3): 346-364.</ref> In Alabama, it is scattered throughout the state in open woodlands.<ref>Woods, M. (2008). "The genera Desmodium and Hylodesmum (Fabaceae) in Alabama." Castanea 73(1): 46-69.</ref> | ||

| + | ''D. rotundifolium'' responds positively to clearcutting and chopping in South Carolina.<ref>Cushwa, C.T. and M.B. Jones. (1969). Wildlife Food Plants on Chopped Areas in Piedmont South Carolina. Note SE-119. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station. 4 pp.</ref> | ||

Associated species include ''Desmodium lineatum, Desmodium ochroleucum, Rhynchosia difformis, Smilax pumila, Rhus aromatica''.<ref name=fsu/> | Associated species include ''Desmodium lineatum, Desmodium ochroleucum, Rhynchosia difformis, Smilax pumila, Rhus aromatica''.<ref name=fsu/> | ||

Revision as of 20:26, 10 July 2019

| Desmodium rotundifolium | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John R. Gwaltney, Southeastern Flora.com | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae ⁄ Leguminosae |

| Genus: | Desmodium |

| Species: | D. rotundifolium |

| Binomial name | |

| Desmodium rotundifolium DC. | |

| |

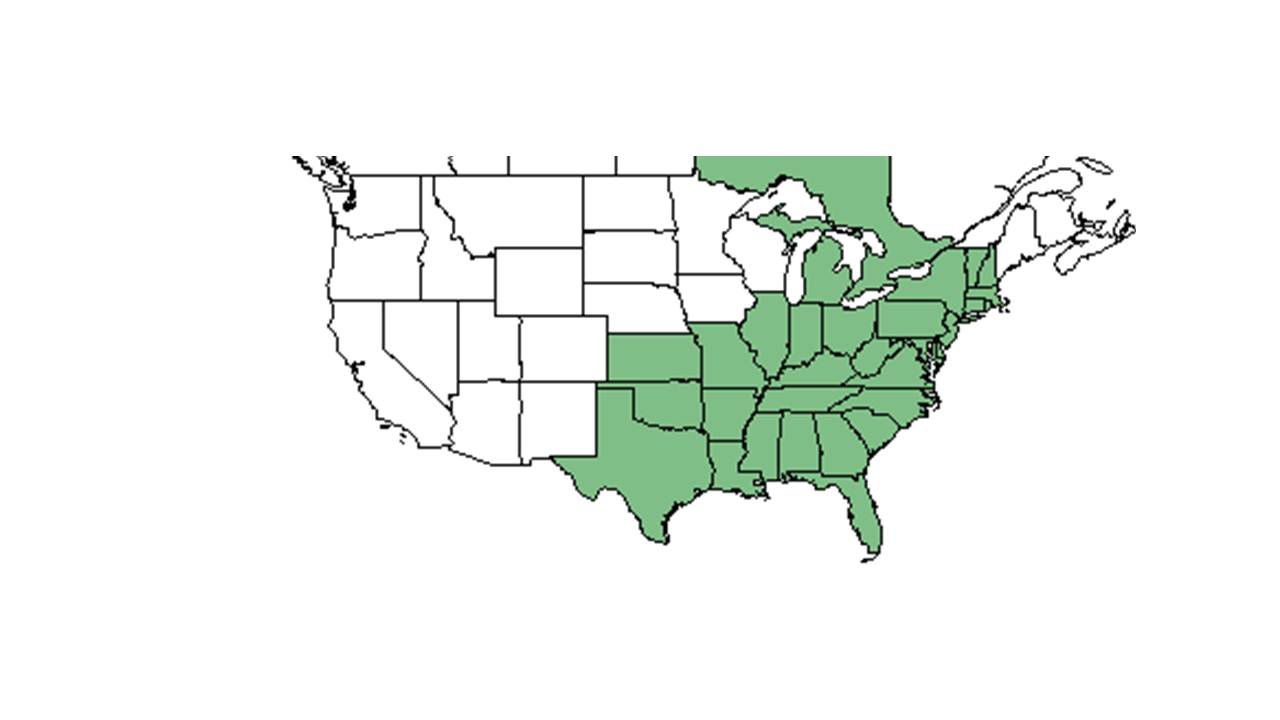

| Natural range of Desmodium rotundifolium from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Roundleaf Tick-trefoil

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonym: Meibomia michauxii Vail

Description

Flowers may be blue or light purple in northern states. In southern areas, fresh corollas are rosy pink, then fading into a whitish color with age. Creeping and trailing habit and prostrate.[1]

Generally, for Desmodium genus, they are "annual or perennial herbs, shrubs or small trees. Leaves 1-5 foliolate, pinnately 3-foliolate in ours or rarely the uppermost or lowermost 1-foliolate; leaflets entire, usually stipellate; stipules caduceus to persistent, ovate to subulate, foliaceous to setaceous, often striate. Inflorescence terminal and from the upper axils, paniculate or occasionally racemose; pedicel of each papilionaceous flower subtended by a secondary bract or bractlet, the cluster of 1-few flowers subtended by a primary bract. Calyx slightly to conspicuously 2-lipped, the upper lip scarcely bifid, the lower lip 3-dentate; petals pink, roseate, purple, bluish or white; stamens monadelphous or more commonly diadelphous and then 9 and 1. Legume a stipitate loment, the segments 2-many or rarely solitary, usually flattened and densely uncinated-pubescent, separating into 1-seeded, indehiscent segments." [2]

Specifically, for D. rotundifolium species, they are "perennial with trailing, densely villous or very rarely glabrate stems 0.5-1.5 m long. Terminal leaflets suborbicular to widely rhombic or obovate, 3-7 cm long, densely appressed to spreading pilose on both surfaces; stipules persistent, ovate, obliquely and widely clasping at base, 8-12 mm long; stipels usually persistent. Inflorescences typically axillary, occasionally terminal, racemose to paniculate; pedicels 6-13 mm long. Calyx sparsely pilose to puberulent; petals purple, 8-10 mm long; stamens diadelphous. Loment of (3) 4-6 segments, each 5-7 mm long, 4-5 broad, both sutures and sides densely uncinlate, both margins about equally indented; stipe 2.5-5 mm long, mostly included within calyx tube and exceeded by stamina remnants." [2]

Distribution

D. rotundifolium is native to the United States from Vermont and Massachusetts west to south Michigan, and south to northeast Florida and the panhandle, Louisiana, and Missouri.[3]

Ecology

Habitat

Generally, D. rotundifolium can be found in woodlands and dry forests.[3] As well, it has been observed to be found in mixed hardwoods, in lightly wooded hillsides, dry glacial drift, and open woods. It requires shaded areas, and is associated with drying sandy loam soil types.[1] It is an upland species, and is not found in any wetlands or mesic habitats.[4] In Alabama, it is scattered throughout the state in open woodlands.[5] D. rotundifolium responds positively to clearcutting and chopping in South Carolina.[6]

Associated species include Desmodium lineatum, Desmodium ochroleucum, Rhynchosia difformis, Smilax pumila, Rhus aromatica.[1]

Phenology

This species generally flowers from June to August and fruits from August to October.[3] D. rotundifolium has been observed flowering in April and from August through October and has been seen fruiting in September. [7][1]

Fire ecology

It becomes more robust in response to fire.[1] D. rotundifolium increases more in frequency in response to summer burn regiments rather than spring burn regiments.[8]

Use by animals

D. rotundifolium consists of approximately 10-25% of the diet for large mammals and terrestrial birds.[9] The leaves are browsed by deer. The seeds are consumed by bobwhite quail, turkey, and the ruffled Grouse. The plant is a larval host for the variegated frittilary butterfly (Euptoieta claudia) and the southern cloudywing (Thorybes bathyllus). [10]

Conservation and management

D. rotundifolium is listed as threatened by the New Hampshire Division of Land and Forests and by the Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife Nongame and Natural Heritage Program.[11] It is tolerant of the nonselective herbicide imazapyr.[12]

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: L. C. Anderson, Wilson Baker, Patricia Elliot, H. Roth, V Craig, Bill Boothe, Marcia Boothe, Billie Bailey, G. W. Parmelee, H. A. Wahl, Norlan C. Henderson, Harry E. Ahles, R. S. Leisner, H. R. Reed, Charles M. Allen, Peter Raven, Tamra E. Raven, and R. Kral. States and Counties: Indiana: Huntington. Florida: Gadsden, Jackson, and Liberty. Louisiana: Allen. Michigan: Barry. Mississippi: Pearl River. Missouri: Jefferson and Stone. North Carolina: Stanley. Pennsylvania: Bradford and Venango. Tennessee: Grundy.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 604-6. Print.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. K., et al. (1998). "Ecotone characterization between upland longleaf pine/wiregrass stands and seasonally-ponded isolated wetlands." Wetlands 18(3): 346-364.

- ↑ Woods, M. (2008). "The genera Desmodium and Hylodesmum (Fabaceae) in Alabama." Castanea 73(1): 46-69.

- ↑ Cushwa, C.T. and M.B. Jones. (1969). Wildlife Food Plants on Chopped Areas in Piedmont South Carolina. Note SE-119. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station. 4 pp.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 8 DEC 2016

- ↑ Cushwa, C. T., et al. (1970). Response of legumes to prescribed burns in loblolly pine stands of the South Carolina Piedmont. Asheville, NC, USDA Forest Service, Research Note SE-140: 6.

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ http://ozarkedgewildflowers.com/summer-wildflowers/dollar-leaf-desmodium-rotundifolium/ Ozark Edge Wildflowers. Accessed: April 21, 2016.

- ↑ USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 26 April 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ (2000). The role of fire in nongame wildlife management and community restoration: Traditional uses and new directions, Nashville, TN, USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station.