Difference between revisions of "Crotalaria rotundifolia"

(→Ecology) |

|||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

It is the larval host plant for the ceranus blue (''Hemiargus ceraunus'') butterfly.<ref name=regional/> | It is the larval host plant for the ceranus blue (''Hemiargus ceraunus'') butterfly.<ref name=regional/> | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | ===Diseases and parasites=== | ||

| + | ''C. rotundifolia'' can be infected by root-knot nematodes, including ''Meloidogyne arenaria'' and ''M. javanica''.<ref>Quesenberry, K. H., et al. (2008). "Response of native southeastern U.S. legumes to root-knot nematodes." Crop Science 48: 2274-2278.</ref> | ||

==Conservation and management== | ==Conservation and management== | ||

Revision as of 18:06, 22 April 2019

| Crotalaria rotundifolia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo was taken by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae ⁄ Leguminosae |

| Genus: | Crotalaria |

| Species: | C. rotundifolia |

| Binomial name | |

| Crotalaria rotundifolia Walter ex J.F. Gmel. | |

| |

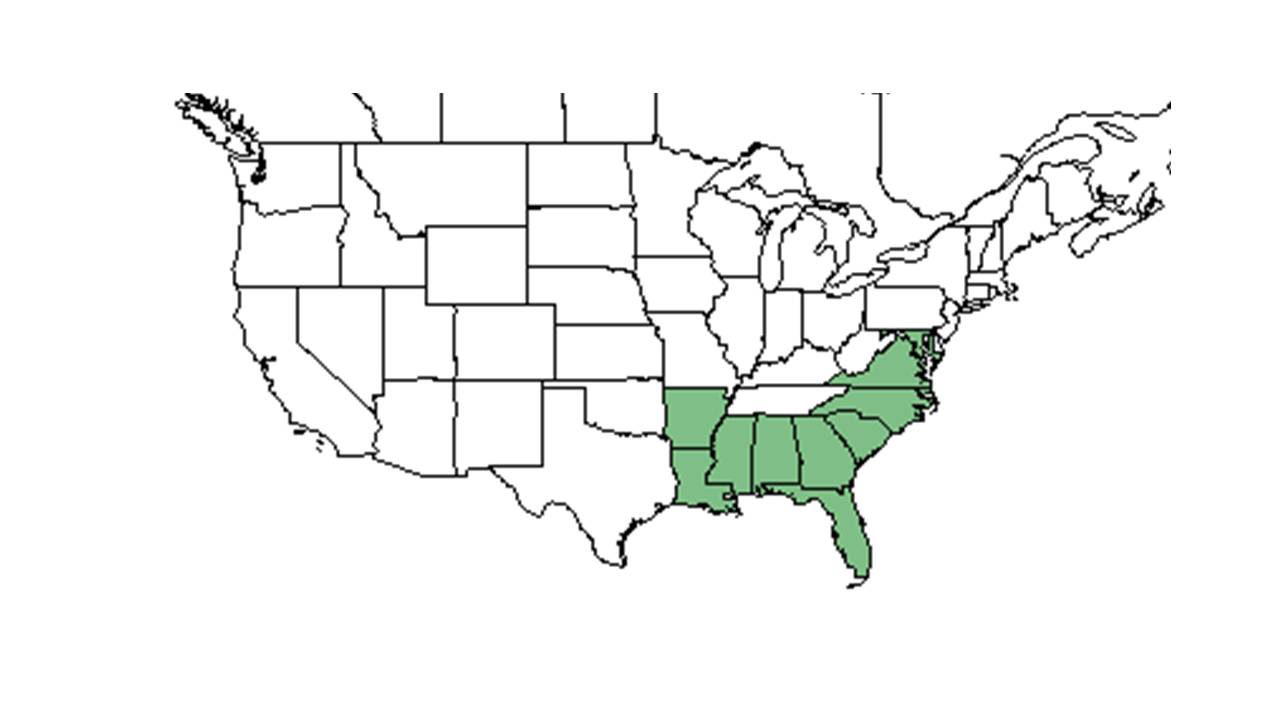

| Natural range of Crotalaria rotundifolia from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Rabbitbells; Low Rattlebox

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonym: Crotalaria rotundifolia Walter ex J.F. Gmelin var. vulgaris Windler

Varieties: none

Description

Perennial herbaceous legume.[1]

Distribution

Southern and eastern United States west to Texas and south to Monroe County, Florida; West Indies, Mexico, and Central America.[2]

Ecology

It is a nitrogen-fixing legume.[3] In a study by Davis, it was discovered that C. rotundifolia had higher mortality and less biomass in high carbon dioxide plots, suggesting that not all species will perform well as global carbon dioxide levels rise.[1]

Habitat

This species is a common associate in longleaf pine savannas.[1] It can also be found in sandhill communities,[4] oak-palmetto scrub, evergreen-scrub oak sand ridges, slash pine flatwoods, sand dunes, backdunes, dune swales, and bordering cypress swamps and depression marshes.[5] This species also occurs in disturbed areas including roadsides, clearings in turkey oak barrens, and clear-cut flatwoods. C. rotundifolia prefers higher light levels associated with open pinelands, and sandy soil types, both moist and dry, such as coarse sand, drying sand, peaty sand, and sandy clay.[5]

Associated species includes Rhynchospora, Xyris, Longleaf pine, wiregrass, oak, saw palmetto, Quercus laevis, Q. margaretta, Aristida beyrichiana, slash pine, Polygala nana, Cyperus lecontei, Polypremum procumbens, Crotonopsis, Paronychia, Andropogon, Diospyros, Aristida, Cnidoscolus. Eupoatorium compositifolium, Axonopus affinis and others.[5]

Phenology

It has a broad, bimodal flowering phenology with peaks in early April and late fall.[6] Flowering has been observed in March through December with peak inflorescence in April.[7] Fruiting has been observed in April through November. [5] However, in its southern natural regions, C. rotundifolia can flower year-round.[8]

Seed dispersal

Seeds are forcefully expelled after the fruit matures and dries, and ants act as the main dispersal agents. The ballistic dispersal distance was found to be around .94 meters.[4] This species is thought to be dispersed by ants and/or explosive dehiscence. [9]

Fire ecology

Robustness of reproduction is related to burn treatments and season of burn.[6] Seedling emergence has been shown to significantly increase over a year for a burned site rather than an unburned site.[10]

Pollination

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Crotalaria rotundifolia at Archbold Biological Station: [11]

Megachilidae: Megachile brevis pseudobrevis

Use by animals

Caterpillars are often found consuming C. rotundifolia. Ants, especially Pogonomyrmex badius, help disperse the seeds long distances.[4]

It is the larval host plant for the ceranus blue (Hemiargus ceraunus) butterfly.[2]

Diseases and parasites

C. rotundifolia can be infected by root-knot nematodes, including Meloidogyne arenaria and M. javanica.[12]

Conservation and management

This species is listed as endangered by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources. As well, the genus Crotalaria is listed as a noxious weed by the Arkansas State Plant Board.[13]

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Davis, M. A., S. G. Pritchard, et al. (2002). "Elevated atmospheric CO2 affects structure of a model regenerating longleaf pine community." Journal of Ecology 90: 130-140.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 [[1]] Regional Conservation. Accessed: April 15, 2016

- ↑ Runion, G. B., M. A. Davis, et al. (2006). "Effects of elevated atmospheric carbon dioxide on biomass and carbon accumulation in a model regenerating longleaf pine community." Journal of Environmental Quality 35: 1478-1486.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Stamp, N. E. and J. R. Lucas (1990). "Spatial patterns and dispersal distances of explosively dispersing plants in Florida sandhill vegetation." Journal of Ecology 78: 589-600.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: O. Lakela, Loran C. Anderson, Bian Tan, Brenda Herring, Don Herring, Gwynn W. Ramsey, H. Larry Stripling, R.K. Godfrey, John Morrill, R. Kral, C. Jackson, D. B. Ward, A. F. Clewell, J. Beckner, D. Burch, L B Trott, William Reese, Paul Redfearn, H. E. Grelen, R. C. Phillips, L. J. Brass, Ann F. Johnson, J. Sincock, Grady W. Reinert, Mabel Kral, Elmer C. Prichard, Sidney McDaniel, Roomie Wilson, K. Craddock Burks, W. W. Baker, A. Mellon, Richard S. Mitchell, Steve L. Orzell, Edwin L. Bridges, Patricia Elliot, A. H. Curtiss, Kurt E. Blum, Dave Breil, H. A. Lang, R. F. Doren, R. A. Norris, Walter Kittredge, R. Komarek, Chris Cooksey, Kevin Oakes, M. Davis, Cecil R Slaughter, John B. Nelson, Cynthia Aulbach-Smith, Kelley, Batson, S. M. Tracy, D. P. Bain, R. B. Carr, R. L. Wilbur, J A Duke, H. L. Blomquist, William B. Fox, A. E. Radford, H. R. Reed, Barbara Lund, Grelen, and Wilbur H Duncan. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Brevard, Calhoun, Citrus, Clay, Collier, Columbia, Dixie, Duval, Flagler, Franklin, Gadsden, Hamilton, Hernando, Highlands, Indian River, Jackson, Jefferson, Lake, Lee, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Marion, Martin, Monroe, Nassau, Osceola, Orange, Polk, Putnam, Taylor, Santa Rosa, Sarasota, St John’s, Sumter, Suwannee, Volusia, and Wakulla. Georgia: Charlton, Echols, Grady, Lanier, and Thomas. South Carolina: Barnwell, Berkeley, Jasper, and Richland. Mississippi: George, Harrison, Lamar, and Pearl River. Texas: Brazos. North Carolina: Bladen, Carteret, and Wayne. Alabama: Baldwin and Mobile.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Hiers, J. K., R. Wyatt, et al. (2000). "The effects of fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas: is a season selective?" Oecologia 125: 521-530.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 22 APR 2019

- ↑ [[2]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: April 22, 2019

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Parks, G. R. (2007). Longleaf pine sandhill seed banks and seedling emergence in relation to time since fire, University of Florida. Master of Science: 84.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Quesenberry, K. H., et al. (2008). "Response of native southeastern U.S. legumes to root-knot nematodes." Crop Science 48: 2274-2278.

- ↑ USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 22 April 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.