Difference between revisions of "Drosera capillaris"

(→Description) |

Krobertson (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

===Use by animals=== <!--Herbivory, granivory, insect hosting, etc.--> | ===Use by animals=== <!--Herbivory, granivory, insect hosting, etc.--> | ||

| − | Sundews are generalists, preying upon a range of arthropods including those from Diptera (true flies), Collembola (Springtails), and Formicidae (ants). Diet overlap suggests competition occurs between ''D. capillaris'' and predatory insects including wolf spiders (Lycosidae).<ref name="Jennings et al 2010">Jennings D. E., Krupa J. J., Raffel T. R., and Rohr J. R. (2010). Evidence for competition between carnivorous plants and spiders. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.0465 </ref> Although a predator to many insects, the larvae of the plume moth (''Trichoptilus parvulus'') is known to consume ''D. capillaris'' by emerging from hiding at night and eating the stalked glands of the sundew.<ref name="Eisner & Shepherd 1965">Eisner T. and Shepherd J. (1965). Caterpillar feeding on a sundew plant. Science 150(3703):1608-1609</ref> Larger larvae may also consume parts of the leaf blade in addition to the gland.<ref name="Eisner & Shepherd 1965"/> Indirect effects by other organisms also influence the pink sundew. Crayfish mound excavations bury individuals of ''D. capillaris'' as they flatten out | + | Sundews are generalists, preying upon a range of arthropods including those from Diptera (true flies), Collembola (Springtails), and Formicidae (ants). Diet overlap suggests competition occurs between ''D. capillaris'' and predatory insects including wolf spiders (Lycosidae).<ref name="Jennings et al 2010">Jennings D. E., Krupa J. J., Raffel T. R., and Rohr J. R. (2010). Evidence for competition between carnivorous plants and spiders. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.0465 </ref> Although a predator to many insects, the larvae of the plume moth (''Trichoptilus parvulus'') is known to consume ''D. capillaris'' by emerging from hiding at night and eating the stalked glands of the sundew.<ref name="Eisner & Shepherd 1965">Eisner T. and Shepherd J. (1965). Caterpillar feeding on a sundew plant. Science 150(3703):1608-1609</ref> Larger larvae may also consume parts of the leaf blade in addition to the gland.<ref name="Eisner & Shepherd 1965"/> Indirect effects by other organisms also influence the pink sundew. Crayfish mound excavations bury individuals of ''D. capillaris'' as they flatten out causing mortality, especially in smaller individuals.<ref name="Brewer 1999"/> |

<!--==Diseases and parasites==--> | <!--==Diseases and parasites==--> | ||

Revision as of 10:02, 13 December 2017

| Drosera capillaris | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John B | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Nephenthales |

| Family: | Droseraceae |

| Genus: | Drosera |

| Species: | D. capillaris |

| Binomial name | |

| Drosera capillaris Poir. | |

| |

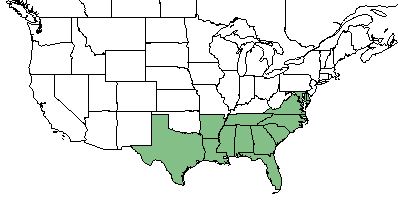

| Natural range of Drosera capillaris from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common Name(s): pink sundew[1][2]

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonym(s): D. rotundifolia var. capillaris, D. sessilifolia, D. brevifolia var. major, D. minor, D. tenella[3]

Description

D. capillaris is a dioecious perennial forb/herb.[2] Stems are 1-2 cm long containing a rosette of leaves. Petioles are 5-10 mm long, glabrous, and dilated. Leaf blades are typically longer than the petiole, measuring 4-10 mm and cuneate. Scapes extend 4-9 cm and are gladular pubescent and bear 1-8 flowers.[4] It also is a carnivorous plant that preys upon many species of arthropods[5] by trapping and digesting them in their mucilaginous secretion known as "dew."[6] Such behavior is seen as an adaptation to overcome the nutrient poor soils with additional sources of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and magnesium,[7][8] although nutrient absorption in the leaves have also been shown to stimulate root nutrient uptake.[7] Seeds are brown elliptic to oblong-ovate (0.4-0.5 mm long), asymmetric, and coarsely papillose-corrugated in 14-16 ridges.[4]

Distribution

Drosera capillaris is found in the southeastern United States ranging from Virginia, south to Florida, and westward to Texas. It can aslo be found in the West Indies, Mexico, and northern South America.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

It is an obligate wetland species[2] being found in pine savannas and other wet sandy or peaty soils.[1]

Phenology

Flowering occurs from March to July but peaks in April and May.[9][10] The probability of a rosette flowering is primarily dependent upon its size.[9] Flowers are about 0.4 in (1 cm) in diameter with pink petals 6-7 mm long and 2-3 mm wide. Sepals are oblong-elliptic stretching 3-4 mm long and 1-2 mm wide and the flowers have 3 styles bipartite to their base.[4]

Seed bank and germination

D. capillaris seeds are reported to be abundant in the seed banks of disturbed and undisturbed long-leaf pine habitat.[11] Emergence of seedlings typically occurs between early winter and late spring.[9]

Fire ecology

Fires facilitate the occurrence of D. capillaris by eliminating or reducing competition.[9] Seedling density also increased following burns, although the growth rates of seedlings remained unaffected.[9] Growth rates are instead dictated by level of competition.[9] Flowering is reported to increase following fires.[12]

Use by animals

Sundews are generalists, preying upon a range of arthropods including those from Diptera (true flies), Collembola (Springtails), and Formicidae (ants). Diet overlap suggests competition occurs between D. capillaris and predatory insects including wolf spiders (Lycosidae).[5] Although a predator to many insects, the larvae of the plume moth (Trichoptilus parvulus) is known to consume D. capillaris by emerging from hiding at night and eating the stalked glands of the sundew.[13] Larger larvae may also consume parts of the leaf blade in addition to the gland.[13] Indirect effects by other organisms also influence the pink sundew. Crayfish mound excavations bury individuals of D. capillaris as they flatten out causing mortality, especially in smaller individuals.[9]

Conservation and Management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Weakley A. S.(2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 30 November 2017). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ Wunderlin R. P., Hansen B. F., Franck A. R. and Essig. F. B. (2017). Atlas of Florida Plants (http://florida.plantatlas.usf.edu/).[S. M. Landry and K. N. Campbell (application development), USF Water Institute.] Institute for Systematic Botany, University of South Florida, Tampa.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Wynne F. E. (1944). Drosera in eastern North America. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 71(2):166-174.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Jennings D. E., Krupa J. J., Raffel T. R., and Rohr J. R. (2010). Evidence for competition between carnivorous plants and spiders. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.0465

- ↑ Dexheimer J. (1978). Study of mucilage secretion by the cells of the digestive glands of Drosera capensis L. using staining of the plasmalemma and mucilage by phosphotungstic acid. Cytologia 43(1):45-52.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Adamec L. (2002). Leaf absorption of mineral nutrients in carnivorous plants stimulates root nutrient uptake. New Phytologist 155(1):89-100.

- ↑ Ellison A. M. (2006). Nutrient Limitation and Stoichiometry of Carnivorous Plants. Plant Biology 8(6):740-747.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 Brewer J. S. (1999). Effects of fire, competition and soil disturbances on regeneration of a carnivorous plant (Drosera capillaris). American Midland Naturalist 141:28-42.

- ↑ Nelson G. (6 December 2017) PanFlora. Retrieved from gilnelson.com/PanFlora/

- ↑ Cohen S., Braham R., and Sanchez F. (2004). Seed bank viability in disturbed long-leaf pine sites. Restoration Ecology 12(4):503-515.

- ↑ Hinman S. E. and Brewer J. S. (2007). Responses of two frequently-burned wet pine savannas to an extended period without fire. Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 134(4):512-526.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Eisner T. and Shepherd J. (1965). Caterpillar feeding on a sundew plant. Science 150(3703):1608-1609