Difference between revisions of "Salix caroliniana"

Krobertson (talk | contribs) (→Seed bank and germination) |

Krobertson (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ||

| − | Lee et al. (2005) found that the initial response of ''S. caroliniana'' to fire was prolific resprouting with the stem density returning to pre-fire levels by the second year post fire. Dormant season fires are effective in reducing cover and basal areas. Repeated fires are more effective than a single fire<ref name="lee2005">Lee, M. A. B., K. L. Snyder, et al. (2005). "Dormant season prescribed fire as a management tool for the control of Salix caroliniana in a floodplain marsh." Wetlands Ecology and Management 13(4): 479-487.</ref> | + | Lee et al. (2005) found that the initial response of ''S. caroliniana'' to fire was prolific resprouting with the stem density returning to pre-fire levels by the second year post fire. Dormant season fires are effective in reducing cover and basal areas. Repeated fires are more effective than a single fire.<ref name="lee2005">Lee, M. A. B., K. L. Snyder, et al. (2005). "Dormant season prescribed fire as a management tool for the control of Salix caroliniana in a floodplain marsh." Wetlands Ecology and Management 13(4): 479-487.</ref> |

===Pollination=== | ===Pollination=== | ||

Revision as of 17:14, 18 August 2016

| Salix caroliniana | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Wayne Matchett, SpaceCoastWildflowers.com | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Salicales |

| Family: | Salicaceae |

| Genus: | Salix |

| Species: | S. caroliniana |

| Binomial name | |

| Salix caroliniana Michx. | |

| |

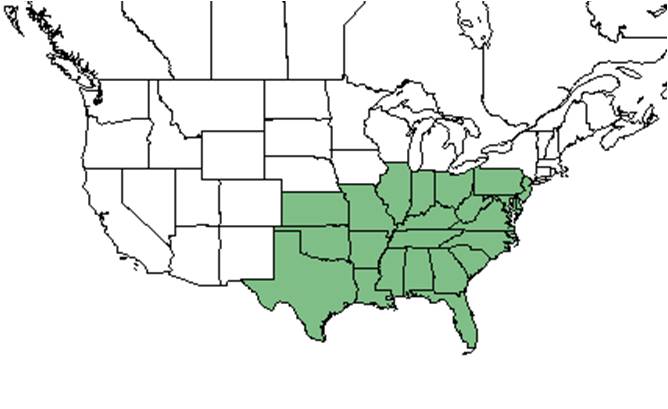

| Natural range of Salix caroliniana from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: coastal plain willow

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Salix amphibia Small; S. longipes Andersson

Description

A description of Salix caroliniana is provided in The Flora of North America.

Distribution

Distributed from eastern and central United States west to Texas and south to Miami-Dade county, Florida.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

Salix caroliniana occurs in creek bottomlands, river banks, cypress swamps, river floodplains, wet coastal hammocks, margin of sawgrass swales, Eichornia bogs, tropical evergreen hardwood forests, border of cypress-gum depression in wet flatwoods, shallow water of a slow moving tributary of a river, marsh edges, mesic pinewoods, wet sloughs, and mesic hardwood swamps. It has also occurred in disturbed areas such as a willow thicket in a broad drainage area between the highway and a railway, roadside canals, swampy edges of an orange grove, waste areas, and powerline corridors.[2] Soil types include loamy soil, sandy silt, loam, and loamy sand. Associated species include Persea, Salix nigra, Equisetum hymale, Saururus cernuus, Rumex verticillatus, R. hastatulus, Tradescantia ohiensis, Xanthosoma sagittifolium, Commelina diffusa, Carex longii, Parietaria floridana, Ludwigia peruviana, Eleocharis geniculata, Carpinus caroliniana, Nyssa sylvatica, and Nyssa aquatica.

In wetland areas of human influence that have altered marsh nutrients, hydrology, and fire intervals, the native Carolina willow can be an invasive species. Expansion of this species has transformed herbaceous marshes, wet prairies, and sloughs into nearly monospecific willow shrub swamps. Traits such as sexual and vegetative reproduction and quickly germinating seeds allows for rapid colonization in disturbed wetlands.[3]

Phenology

Flowers and fruits January through August.[2] This is a dioecious species with the yellow male flowers arranged in catkins while female individuals have a cluster of small fruit with white plume-like hairs.[4]

Seed dispersal

Seeds are dispersed by wind and running water.[3]

Seed bank and germination

Seeds do not exhibit dormancy and germinate rapidly.[3] The seeds have short viability and germination is very sensitive to drought and flooding.[5]

Fire ecology

Lee et al. (2005) found that the initial response of S. caroliniana to fire was prolific resprouting with the stem density returning to pre-fire levels by the second year post fire. Dormant season fires are effective in reducing cover and basal areas. Repeated fires are more effective than a single fire.[6]

Pollination

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Salix caroliniana at Archbold Biological Station: [7]

Apidae: Apis mellifera

Colletidae: Colletes brimleyi, Hylaeus confluens

Halictidae: Lasioglossum lepidii, L. pectoralis, L. placidensis, L. puteulanum

Leucospididae: Leucospis affinis

Sphecidae: Ectemnius decemmaculatus tequesta

Vespidae: Parancistrocerus perennis anacardivora, Polistes fuscatus, Stenodynerus histrionalis rufustus, Vespula squamosa, Zethus slossonae

Use by animals

Ducks and water birds eat the catkins and leaves, twigs and leaves are consumed by deer, and shoots and buds are eaten by rodents including muskrats and beavers as well as cottontail rabbits[8].

The only larval host plant for viceroy (Limenitis archippus) butterflies and Automeris io moths[1].

Conservation and management

In wetland areas that have altered hydrology, nutrients and fire suppression, S. caroliniana can invasively spread creating nearly monospecific willow shrub swamps[3].Hydrological manipulations can aide in controlling the establishment and early growth of S. caroliniana. Seeds have short viability and germination is sensitive to drought and flooding, therefore timely desiccation and flooding can control willows by killing seedlings and reducing growth of cuttings[5]. Ponzio et al. (2006) found that under dry conditions followed by flooding, roller-chopping can be an effective method of willow control. Lee et al. (2005) states that dormant season fires are effective in reducing S. caroliniana cover and basal area and repeated fires have greater effects than a single fire.

Cultivation and restoration

The stems of S. caroliniana have been used for basketry, fences and furniture. The sap contains salicylic acid, which is a natural ingredient of aspirin[8].

Photo Gallery

References and notes

Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: November 2015. Collectors: J. Richard Abbott, Harry E. Ahles, Loran C. Anderson, L. Baltzell, A.S. Barclay, Tom Barnes, L.J. Brass, Dana Bryan, Nancy Coile, Kathy Craddock Burks, Delzie Demaree, R.F. Doren, J.A. Duke, Donna Marie Eggers, Patricia Elliott, E.S. Ford, Angus Gholson, Robert K. Godfrey, James W. Hardin, Robert R. Haynes, Mary C. Helms, R.D. Houk, S.B. Jones, Walter S. Judd, H. Kurz, Robert Kral, O. Lakela, Alex Lasseigne, Robert J. Lemaire, S.W. Leonard, Elbert L. Little Jr., Richard S. Mitchell, T. Myint, J.B. Nelson, Hugh O’Neill, R.A. Norris, Elmer C. Prichard, J.T. Powell, P.L. Redfearn Jr., A.J. Sharp, Cecil R. Slaughter, R.R. Smith, Edward E. Terrell, D.B. Ward, Christine Wilton. States and Counties: Alabama: Crenshaw, Perry.Arkansas: Searcy, Saline, Van Buren. Florida: Bay, Dade, Dixie, Franklin, Gadsden, Glades, Gulf, Hernando, Hillsborough, Holmes, Indian River, Jackson, Jefferson, Lafayette, Lake, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Marion, Martin, Nassau, Orange, Pinellas, Putnam, Santa Rosa, St. Johns, Suwannee, Taylor, Volusia, Wakulla, Walton. Georgia: Bulloch, Camden, Decatur, McIntosh, Seminole. Missouri: Douglas, Greene, Iron, Stone, Taney. North Carolina: Beaufort, Craven, Hyde, Iredell, Perquimans, Pitt. South Carolina: Colleton. Tennessee: Dickson, Lewis. West Virginia: Raleigh. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 [[1]]Regional conservation. Accessed: March 15, 2016

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: November 2015. Collectors: J. Richard Abbott, Harry E. Ahles, Loran C. Anderson, L. Baltzell, A.S. Barclay, Tom Barnes, L.J. Brass, Dana Bryan, Nancy Coile, Kathy Craddock Burks, Delzie Demaree, R.F. Doren, J.A. Duke, Donna Marie Eggers, Patricia Elliott, E.S. Ford, Angus Gholson, Robert K. Godfrey, James W. Hardin, Robert R. Haynes, Mary C. Helms, R.D. Houk, S.B. Jones, Walter S. Judd, H. Kurz, Robert Kral, O. Lakela, Alex Lasseigne, Robert J. Lemaire, S.W. Leonard, Elbert L. Little Jr., Richard S. Mitchell, T. Myint, J.B. Nelson, Hugh O’Neill, R.A. Norris, Elmer C. Prichard, J.T. Powell, P.L. Redfearn Jr., A.J. Sharp, Cecil R. Slaughter, R.R. Smith, Edward E. Terrell, D.B. Ward, Christine Wilton. States and Counties: Alabama: Crenshaw, Perry.Arkansas: Searcy, Saline, Van Buren. Florida: Bay, Dade, Dixie, Franklin, Gadsden, Glades, Gulf, Hernando, Hillsborough, Holmes, Indian River, Jackson, Jefferson, Lafayette, Lake, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Marion, Martin, Nassau, Orange, Pinellas, Putnam, Santa Rosa, St. Johns, Suwannee, Taylor, Volusia, Wakulla, Walton. Georgia: Bulloch, Camden, Decatur, McIntosh, Seminole. Missouri: Douglas, Greene, Iron, Stone, Taney. North Carolina: Beaufort, Craven, Hyde, Iredell, Perquimans, Pitt. South Carolina: Colleton. Tennessee: Dickson, Lewis. West Virginia: Raleigh. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Castro-Morales, L. U. Z., P. F. Quintana-Ascencio, et al. (2014). "Environmental factors affecting germination and seedling survival of Carolina willow (Salix caroliniana)." Wetlands 34: 469-478.

- ↑ [[2]]Accessed: March 16, 2016

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Quintana-Ascencio, P. F., J. E. Fauth, et al. (2013). "Taming the Beast: Managing Hydrology to Control Carolina Willow (Salix caroliniana) Seedlings and Cuttings." Restoration Ecology 21(5): 639-647.

- ↑ Lee, M. A. B., K. L. Snyder, et al. (2005). "Dormant season prescribed fire as a management tool for the control of Salix caroliniana in a floodplain marsh." Wetlands Ecology and Management 13(4): 479-487.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 [[3]]Florida Native Plant Society. Accessed: March 15, 2016