Difference between revisions of "Opuntia humifusa"

Krobertson (talk | contribs) (→Seed bank and germination) |

Krobertson (talk | contribs) (→Cultivation and restoration) |

||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

==Cultivation and restoration== | ==Cultivation and restoration== | ||

| − | Native Americans used the pads to heal wounds, warts, and drank pad tea for respiratory issues <ref name="wildflower"/> | + | Native Americans used the pads to heal wounds, warts, and drank pad tea for respiratory issues.<ref name="wildflower"/> |

==Photo Gallery== | ==Photo Gallery== | ||

Revision as of 13:09, 18 August 2016

| Opuntia humifusa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Wayne Matchett, SpaceCoastWildflowers.com | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Caryophyllales |

| Family: | Cactaceae |

| Genus: | Opuntia |

| Species: | O. humifusa |

| Binomial name | |

| Opuntia humifusa (Raf.) Raf. | |

| |

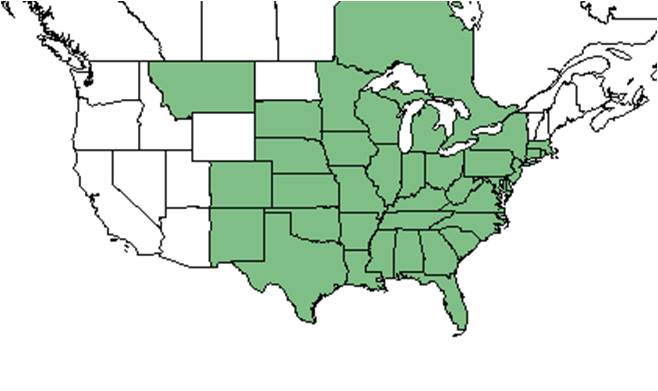

| Natural range of Opuntia humifusa from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: devil's-tongue, eastern prickly pear

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Opuntia humifusa (Rafinesque) Rafinesque var. humifusa; O. compressa (Salisbury) J.F. Macbride var. compressa; O. compressa; O. impedita Small; O. macrarthra Gibbes; O. opuntia (Linnaeus) Karten; O. calcicola Wherry; O. rafinesquei Engelmann

Description

A description of Opuntia humifusa is provided in The Flora of North America.

Distribution

It is the only cactus to be widespread in the eastern United States. [1] It is found in southern Canada as well as the eastern United States. [2]

Ecology

Habitat

Opuntia humifusa can occur in upland longleaf pines, sand dunes, Pinus clausa scrubs, open sand flats, sandhills, and pine/oak scrubs. It has been found in disturbed areas such as loblolly tree farms and roadside depressions. Associated species include Lyonia ferruginea, Lyonia lucida, Serenoa repens, Quercus geminata, Q. chapmanii, Persea humilis, Ceratiola, Osmanthus megacarpus, Rhynchospora megalocarpa, Galactia elliottii, and Smilax auriculata.[3]

It occurs in southern Canada, where average nighttime temperatures can reach -4 degrees Celsius. In order to prevent intracellular freeze dehydration and ice formation, individuals have an accumulation of sugars and mannitol in their cells. [2]

Phenology

It has been observed flowering April through July and fruiting January, May and December.[3]

Root stocks and detached cladodes can propagate vegetatively for up to 12 months after detachment. [2]

Seed dispersal

The fruit is eaten and dispersed by birds, rabbits, woodrats, prairie-dogs, mice, ground squirrels, and white-tailed deer. [4] According to Kay Kirkman, a plant ecologist, this species disperses by being consumed by vertebrates (being assumed). [5]

Seed bank and germination

Germination rate is low.[4]

Pollination

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Opuntia humifusa at Archbold Biological Station: [6]

Apidae: Apis mellifera, Bombus impatiens, B. pennsylvanicus, Mellisodes communis

Halictidae: Agapostemon splendens, Augochlorella aurata, Augochloropsis sumptuosa, Halictus poeyi, Lasioglossum nymphalis, L. puteulanum

Megachilidae: Dianthidium floridiense, Lithurgus gibbosus, Megachile brevis pseudobrevis, M. policaris

Use by animals

It is an important food for pocket gophers. [7] It is a host to the invasive cactus moth (Cactoblastis cactorum). [8] The large pads provides nesting to bobwhite quail. [9]

Conservation and management

Cultivation and restoration

Native Americans used the pads to heal wounds, warts, and drank pad tea for respiratory issues.[1]

Photo Gallery

Flowers of Opuntia humifusa Photo by Wayne Matchett, SpaceCoastWildflowers.com

References and notes

Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: October 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Michael Blaker, M. Borgman, James R. Burkhaulter, George R. Cooley, R.J. Eaton, Patricia Elliott, J. Kevin England, Robert K. Godfrey, Darren Jackson, Ed Keppner, Lisa Keppner, Andrew McAllister, Sidney McDaniel, K.M. Meyer, James D. Ray Jr., Erik Robinson, L. Rosen, C.E. Smith, A. Townesmith, Kenneth A. Wilson, Carroll E. Wood Jr.. States and Counties: Alabama: Dale. Florida: Alabama, Escambia, Franklin, Gadsden, Hernando, Jackson, Lafayette, Leon, Liberty, Orange, Putnam, Seminole, Walton, Wakulla, Washington. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: February 12, 2016

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Goldstein, G. and P. S. Nobel (1994). "Water Relations and Low-Temperature Acclimation for Cactus Species Varying in Freezing Tolerance." Plant Physiology 104(2): 675-681.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedFSU Herbarium - ↑ 4.0 4.1 [[2]] Accessed: February 13, 2016

- ↑ Kay Kirkman, unpublished data, 2015.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Myers, G. T. and T. A. Vaughan (1964). "Food Habits of the Plains Pocket Gopher in Eastern Colorado." Journal of Mammalogy 45(4): 588-598.

- ↑ Jezorek, H. and P. Stiling (2012). "LACK OF ASSOCIATIONAL EFFECTS BETWEEN TWO HOSTS OF AN INVASIVE HERBIVORE: OPUNTIA SPP. AND CACTOBLASTIS CACTORUM (LEPIDOPTERA: PYRALIDAE)." The Florida Entomologist 95(4): 1048-1057.

- ↑ [[3]]Illinois Wildflowers. Accessed: February 15, 2016