Difference between revisions of "Cyperus retrorsus"

(→Conservation and Management) |

|||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

<!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | <!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | ||

| − | ==Conservation and | + | ==Conservation and management== |

| + | |||

==Cultivation and restoration== | ==Cultivation and restoration== | ||

==Photo Gallery== | ==Photo Gallery== | ||

Revision as of 19:50, 20 June 2016

| Cyperus retrorsus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Dwight K. Lauer, Auburn University, Bugwood.org | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida – Monocotyledons |

| Order: | Cyperales |

| Family: | Cyperaceae |

| Genus: | Cyperus |

| Species: | C. retrorsus |

| Binomial name | |

| Cyperus retrorsus Chapm. | |

| |

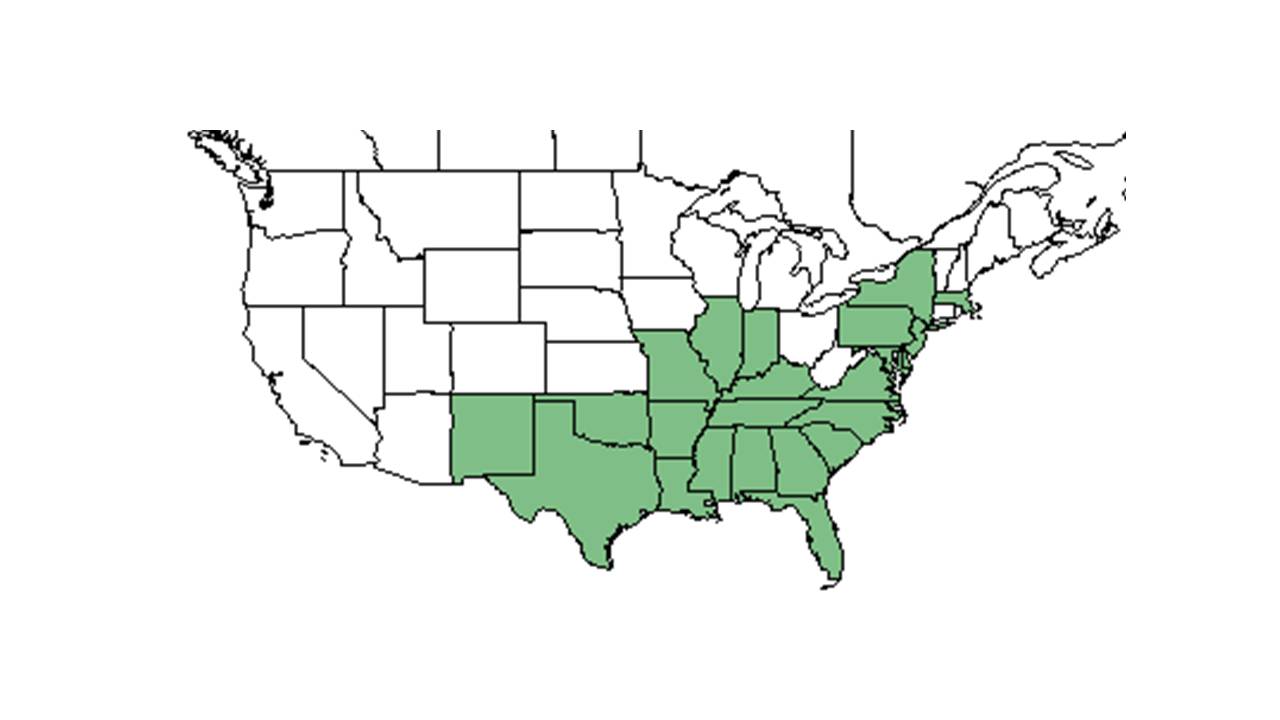

| Natural range of Cyperus retrorsus from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: pine barren flatsedge

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Cyperus retrorsus Chapman var. retrorsus; C. torreyi Britton

Description

A description of Cyperus retrorsus is provided in The Flora of North America. Cyperus retrorsus is a perennial graminoid. Most individuals are composed of 1-3 stems. [1]

Distribution

Ecology

Habitat

C. retrorsus requires wet summers and dry winters.[2] It also prefers higher light levels associated with open or semi-shaded conditions, and moist to wet sandy soils. [1] It has been observed growing in a variety of related soil types, including wet sand, moist sandy peat, moist loamy sand, drying sandy soil, drying loam, peat, and dry sterile sand. [1]

As such, this species can be found in or near wet habitat like pocosin communities[3], lake shores, phosphate pools, marshes, lakeside sinkhole berms, drained bogs, river floodplains, seepage streams, and drying wetland depressions. [1] However, it also can be found in drier areas, including flatwoods communities[4], and longleaf pine communities[5]. Additionally, it has been found in oak-hickory forests, grassy areas on islands, turkey oak sand ridges, sandhills, live oak hammocks, dried lake bottoms, pine flatwoods-savannas, old stabilized sand dunes, prairies, open scrub, and scrub barrens. [1]

Along with being found in natural community types, C. retrorsus has been found in disturbed habitat such as cleared floodplains, roadside ditches, railways, trail edges, clear-cuts, fallow fields, borrow pits, dredge spoils, former pine plantations, orange groves, longleaf pine restoration sites, and disturbed sandhill communities. [1]

Associated species include Paspalum notatum, Eupatorium mohrii, Rubus cuneifolius, Ludwigia maritima, Pityopsis, Solidago fistulosa, Aletris lutea, Eleusine, Dactyloctenium, Digitaria, Panicum, Rhynchospora fernaldii, R. fasicularis, Andropogon, Scleria reticularis, Trilisa, Liatris, Aristida, Andropogon, Bulbostylis, Clitoria, Juncus, Pteridium aquilinum, Cyperus filiculmis, Commelina erecta, Serenoa repens, Sagittaria graminea, Woodwardia virginica, Nyssa biflora, Acer rubrum, Liquidambar styraciflua, Rynchospora fernaldii, R. fascicularis, Carex longii, madien cane, and others. [1]

Phenology

Flowering has been observed in July through October. [1]

Seed dispersal

According to Kay Kirkman, a plant ecologist, this species disperses by gravity. [6]

Seed bank and germination

It accounted for 29% of a late-summer Virginia pocosin seed bank.[3]

Fire ecology

C. cyperus has been found in burned areas including recently burned slash pine-scrub flat, annually burned savanna, and frequently burned mature longleaf pine-wiregrass communities, indicating a level of fire tolerance. [1]

It responds best to a moderate-severity level burn. Recovery after fire is achieved by resprouting and seed.[2] Abundance was found to significantly decrease over 25 years after fire in a scrubby flatwoods, suggesting the significance of fire in its life history.[7]

Conservation and management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: S. W. Leonard, R.K. Godfrey, Angus Gholson, D. S. Correll, Helen B. Correll, Andre F. Clewell, Loran C. Anderson, Nancy Coile, S. W. Leonard, Richard Carter, Cecil R Slaughter, Travis MacClendon, Karen MacClendon, R. Kral, James P. Gillespie, A. H. Curtiss, O. Lakela, S. M. Tracy, Robert L. Lazor, K. Craddock Burks, R. R. Smith, Gary R. Knight, H. Kurz, Richard S. Mitchell, Grady W. Reinert, P. L. Redfearn, Jr., Allen G. Shuey, D. L. Martin, S. T. Cooper, Brenda Herring, Don Herring, William Reese, Bruce Hansen, JoAnn Hansen, Sidney McDaniel, D. B. Ward, R. A. Norris, Chris Cooksey, R. Komarek, Ann F. Johnson, Lisa Keppner, Michael Keys, and Paul Redfearn. States and Counties: Alabama: Geneva. Florida: Bay, Brevard, Calhoun, Charlotte, Clay, Collier, Columbia, Duval, Escambia, Franklin, Gadsden, Gilchrist, Gulf, Highlands, Hillsborough, Indian River, Jackson, Jefferson, Lake, Lamar, Leon, Liberty, Madison, Manatee, Marion, Okaloosa, Orange, Osceola, Pasco, Polk, Putnam, Sarasota, Sumter, Taylor, Wakulla, Walton, and Washington. Georgia: Grady, Liberty, and Thomas.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Freeman, J. E. and L. N. Kobziar (2011). "Tracking postfire successional trajectories in a plant community adapted to high-severity fire." Ecological Applications 21: 61-74.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Bolin, J. F. (2007). "Seed bank response to wet heat and the vegetation structure of a Virginia pocosin." Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 134: 80-88.

- ↑ Kalmbacher, R., N. Cellinese, et al. (2005). "Seeds obtained by vacuuming the soil surface after fire compared with soil seedbank in a flatwoods plant community." Native Plants Journal 6: 233-241.

- ↑ Ruth, A. D., S. Jose, et al. (2008). "Seed bank dynamics of sand pine scrub and longleaf pine flatwoods of the Gulf Coastal Plain (Florida)." Ecological Restoration 26: 19-21.

- ↑ Kay Kirkman, unpublished data, 2015.

- ↑ Menges, E. S. and N. M. Kohfeldt (1995). "Life History Strategies of Florida Scrub Plants in Relation to Fire." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 122(4): 282-297.