Difference between revisions of "Desmodium floridanum"

ParkerRoth (talk | contribs) (→Description) |

Adam.Vansant (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

''Desmodium floridanum'' is an indicator species for the North Florida Subxeric Sandhills community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).<ref>Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.</ref> | ''Desmodium floridanum'' is an indicator species for the North Florida Subxeric Sandhills community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).<ref>Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''D. floridanum'' was found to be neutral in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.<ref name=Dixon>Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.</ref> | ||

===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ||

Latest revision as of 17:43, 1 August 2024

| Desmodium floridanum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae ⁄ Leguminosae |

| Genus: | Desmodium |

| Species: | D. floridanum |

| Binomial name | |

| Desmodium floridanum Chapm. | |

| |

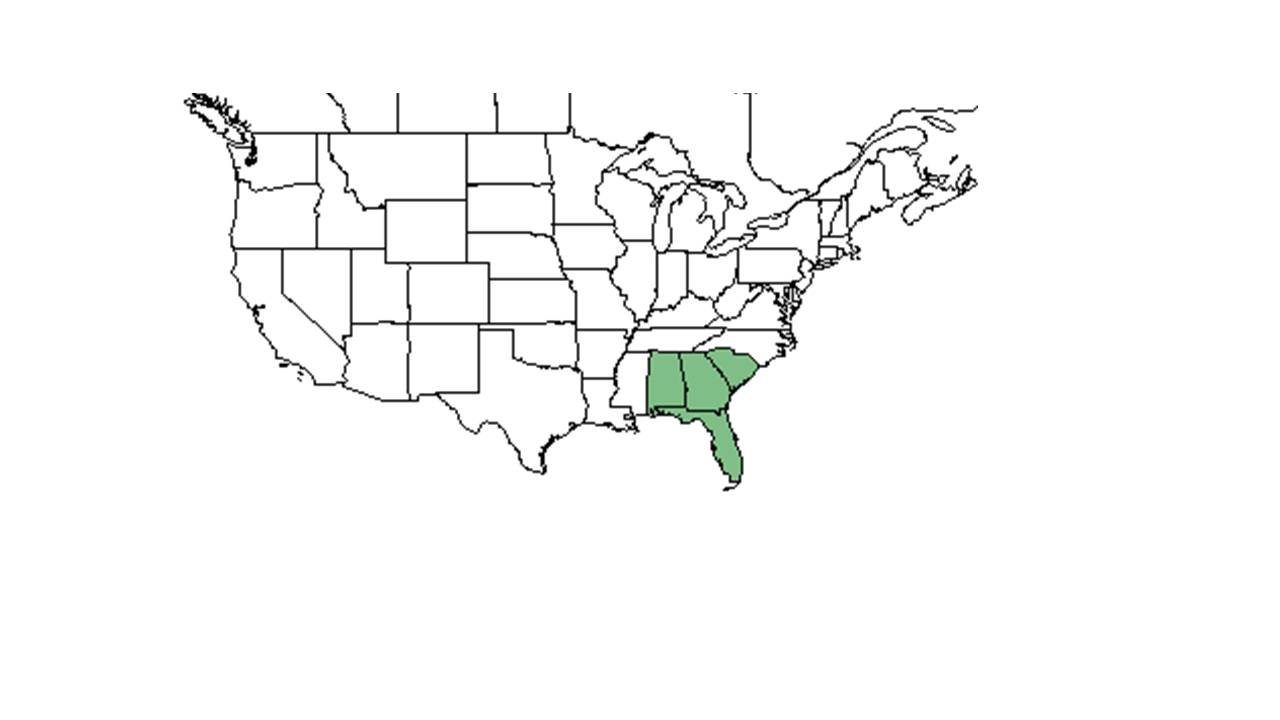

| Natural range of Desmodium floridanum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Florida tick-trefoil

Contents

[hide]Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: none[1]

Varieties: none[1]

Description

Generally, the Desmodium genus species are "annual or perennial herbs, shrubs or small trees. Leaves 1-5 foliolate, pinnately 3-foliolate in ours or rarely the uppermost or lowermost 1-foliolate; leaflets entire, usually stipellate; stipules caduceus to persistent, ovate to subulate, foliaceous to setaceous, often striate. Inflorescence terminal and from the upper axils, paniculate or occasionally racemose; pedicel of each papilionaceous flower subtended by a secondary bract or bractlet, the cluster of 1-few flowers subtended by a primary bract. Calyx slightly to conspicuously 2-lipped, the upper lip scarcely bifid, the lower lip 3-dentate; petals pink, roseate, purple, bluish or white; stamens monadelphous or more commonly diadelphous and then 9 and 1. Legume a stipitate loment, the segments 2-many or rarely solitary, usually flattened and densely uncinated-pubescent, separating into 1-seeded, indehiscent segments."[2]

Specifically, the D. floridanum species are"erect perennial; stem to 5 dm tall, mostly uncinatepubescent, occasionally interspersed with pilose trichomes. Leaves mostly 1-foliolate below, 3-foliolate above. Terminal leaflets rhombic to deltoid or ovate, 4-9 cm long, uncinulate puberlent and softly pilose beneath; stipules persistent, lance-ovate to ovate-attenuate, 4-10 mm long; stipels persistent. Inflorescence racemose to paniculate, uncinulate-puberulent; pedicels 4.5-8 mm long. Calyx uncinulate-puberulent and pilose on lobes and upper tube; petals purplish, 6-7.5 mm long; stamens diadelphous. Loment of 3-5 deltoid segments, each 6-7 mm long, 4-5 mm broad, curved on upper suture and broadly rounded below, uncinulate-puberulent on both sides and sutures; stipe 1.5-4 mm long, shorter than the calyx lobes and stamina remnants."[2]

The root system of D. floridanum includes stem tubers which store non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) important for both resprouting following fire and persisting during long periods of fire exclusion.[3] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an NSC concentration of 153 mg/g (ranking 36 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 58.4% (ranking 57 out of 100 species studied).[3]

According to Diaz-Torbio and Putz (2021), Desmodium floridanum has stem tubers with a below-ground to above-ground biomass ratio of 1.54 and nonstructural carbohydrate concentration of 153 mg g-1.[4]

Distribution

D. floridanum is native to the southeast coastal plain from southeast South Carolina to south Florida.[5] However, it is an uncommon species in the communities where it is native.[6]

It is endemic to an area from southern South Carolina to peninsular Florida, but is most common in Florida.[7]

Ecology

Habitat

It is found in upland longleaf and shortleaf pine native communities (Ultisols), pine-oak flatwoods, sand pine-oak scrub (Entisols), longleaf and slash pine flatwoods (Spodosols), edges of hardwood forests. It thrives in frequently burned areas. It occurs in open areas and semi-shaded areas. It can occur in areas with recent soil disturbance and old-field pine forests. It occurs on sandy to loamy soils from xeric to moist conditions.[8] D. floridanum is also an indicator species of the North Florida subxeric sandhills community.[9] It is also a characteristic species of the shortleaf pine-oak-hickory community type in the Red Hills region of north Florida and south Georgia.[10]

Associated species include Desmodium viridiflorum, D.strictum, D. glabellum, Tephrosia, Eryngium yuccifolium, Aristida, Pluchea , Longleaf pine, slash pine, and turkey oak.[8]

Desmodium floridanum is an indicator species for the North Florida Subxeric Sandhills community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[11]

D. floridanum was found to be neutral in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[12]

Phenology

D. floridanum has been observed to flower from April to October with peak inflorescence in July.[13] It fruits from May to October.[8]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by translocation on animal fur or feathers. [14]

Seed bank and germination

Seeds of D. floridanum do not need any scarification before germination since they are soft-shelled. A study found that adding steam heat enhanced germination when conducted for 10 seconds. They also found the seeds to not tolerate higher dry heat values or longer steam durations.[15] Fire disturbance has been shown to decrease germination success.[16]

Fire ecology

D. floridanum grows in sandhill communities that are fire dependent.[9] It proliferates from high fire return intervals,[17] with populations known to persist through repeated annual burns.[18][19] However, the seeds in the seed bank do not germinate well in response to fire.[16]

Herbivory and toxicology

D. floridanum is a food source for bobwhite quail[20] and wild turkey.[21] White tail deer are also attracted to the plant as an important forage source.[22][23][24][25] It is a host plant to the velvet bean caterpillar larvae (Anticarsia gemmatalis).[26]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 604-12. Print.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- Jump up ↑ Diaz‐Toribio, M. H. and F. E. Putz. 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire‐maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108(3):432-442.

- Jump up ↑ Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- Jump up ↑ Woods, M. (2008). "The genera Desmodium and Hylodesmum (Fabaceae) in Alabama." Castanea 73(1): 46-69.

- Jump up ↑ Sorrie, B. A. and A. S. Weakley 2001. Coastal Plain valcular plant endemics: Phytogeographic patterns. Castanea 66: 50-82.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, R. K. Godfrey, R. Kral, V. Sullivan, J. Wooten, Grady W. Reinert, J. N. Triplett, Jr., John B. Nelson, G. Knight, Gwynn W. Ramsey, Richard Mitchell, A. F. Clewell, C. Jackson, H. Roth, V Craig, Bill Boothe, and Marcia Boothe. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Citrus, Columbia, Gadsden, Franklin, Gulf, Jackson, Jefferson, Lafayette, Leon, Levy. Madison, Putnam, Suwannee, and Wakulla. Georgia: Baker, Charlton, McIntosh and Thomas.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.

- Jump up ↑ Clewell, A. F. (2013). "Prior prevalence of shortleaf pine-oak-hickory woodlands in the Tallahassee red hills." Castanea 78(4): 266-276.

- Jump up ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- Jump up ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- Jump up ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 8 DEC 2016

- Jump up ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- Jump up ↑ Wiggers, M. S., et al. (2017). "Seed heat tolerance and germination of six legume species native to a fire-prone longleaf pine forest." Plant Ecology 218: 151-171.

- ↑ Jump up to: 16.0 16.1 Wiggers, M. S., et al. (2013). "Fine-scale variation in surface fire environment and legume germination in the longleaf pine ecosystem." Forest Ecology and Management 310: 54-63.

- Jump up ↑ Mehlman, D. W. (1992). "Effects of fire on plant community composition of North Florida second growth pineland." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 119(4): 376-383.

- Jump up ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- Jump up ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- Jump up ↑ Madison, L. A. and R. J. Robel (2001). "Energy Characteristics and Consumption of Several Seeds Recommended for Northern Bobwhite Food Plantings." Wildlife Society Bulletin (1973-2006) 29(4): 1219-1227.

- Jump up ↑ Denhof, Carol. 2016. Plant Spotlight Downy Beardtongue Penstemon Australis Small. The Longleaf Leader – Working Forests: Balancing the Tradeoffs. Vol. IX. Iss. 3. Page 6

- Jump up ↑ Denhof, Carol. 2016. Plant Spotlight Downy Beardtongue Penstemon Australis Small. The Longleaf Leader – Working Forests: Balancing the Tradeoffs. Vol. IX. Iss. 3. Page 6

- Jump up ↑ Miller, J.H. and K.V. Miller. 2005. Forest Plants of the Southeast and their Wildlife Uses. The University of Georgia Press, Atehns, GA. 454pp.

- Jump up ↑ Norden, H. and L.K. Kirkman. Field Guide to Common Legume Species of the Longleaf Pine Ecosystem. J.W. Jones Ecological Research Center, Newton, GA. 72pp.

- Jump up ↑ USDA, NRCS. 2016 The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 9 May 2016). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- Jump up ↑ Buschman, L. L., W. H. Whitcomb, et al. (1977). "Winter Survival and Hosts of the Velvetbean Caterpillar in Florida." The Florida Entomologist 60(4): 267-273.