Difference between revisions of "Osmundastrum cinnamomeum"

(→Taxonomic Notes) |

|||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

==Description== <!-- Basic life history facts such as annual/perrenial, monoecious/dioecious, root morphology, seed type, etc. --> | ==Description== <!-- Basic life history facts such as annual/perrenial, monoecious/dioecious, root morphology, seed type, etc. --> | ||

| − | ''Osmunda cinnamomea'' is a perennial fern that grows as a forb/herb.<ref name="USDA"/> The leaves are dimorphic and equally broad through much of their length. The basal-most pinnae can be more than 1/2 as long as the largest pinnae. The photosynthetic pinnae have tufts of reddish hairs near the junction with the rachis.<ref name= | + | ''Osmunda cinnamomea'' is a perennial fern that grows as a forb/herb.<ref name="USDA"/> The leaves are dimorphic and equally broad through much of their length. The basal-most pinnae can be more than 1/2 as long as the largest pinnae. The photosynthetic pinnae have tufts of reddish hairs near the junction with the rachis.<ref name=weakley/> |

| − | To distinguish from ''Anchistea virginica'', look for a coarser texture, cinnamon tufts of tomentum in the axils of the pinnae, a greenish and fleshy rachis (vs. brown and wiry), and fronds clumped or tufted from a massive, woody, ascending rhizome covered with old petiole bases (vs. fronds borne scattered along a thick, horizontal, creeping rhizome).<ref name= | + | To distinguish from ''Anchistea virginica'', look for a coarser texture, cinnamon tufts of tomentum in the axils of the pinnae, a greenish and fleshy rachis (vs. brown and wiry), and fronds clumped or tufted from a massive, woody, ascending rhizome covered with old petiole bases (vs. fronds borne scattered along a thick, horizontal, creeping rhizome).<ref name=weakley/> |

Sterile fronds increase their photosynthesis rates in the spring where they level off around 6-8 µmol m<sup>-2</sup> s<sup>-1</sup>. Fertile fronds mature quicker and reached dark respiration rates 2-3 times greater than sterile fronds.<ref name="Britton & Watkins 2016">Britton MR, Watkins Jr. JE (2016) The economy of reproduction in dimorphic ferns. Annals of Botany 118:1139-1149.</ref> | Sterile fronds increase their photosynthesis rates in the spring where they level off around 6-8 µmol m<sup>-2</sup> s<sup>-1</sup>. Fertile fronds mature quicker and reached dark respiration rates 2-3 times greater than sterile fronds.<ref name="Britton & Watkins 2016">Britton MR, Watkins Jr. JE (2016) The economy of reproduction in dimorphic ferns. Annals of Botany 118:1139-1149.</ref> | ||

Revision as of 17:58, 16 June 2023

| Osmundastrum cinnamomeum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John B hosted at Bluemelon.com/poaceae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Pteridophyta – Ferns |

| Class: | Filicopsida |

| Order: | Polypodiales |

| Family: | Osmundaceae |

| Genus: | Osmundastrum |

| Species: | O. cinnamomeum |

| Binomial name | |

| Osmundastrum cinnamomeum L. | |

| |

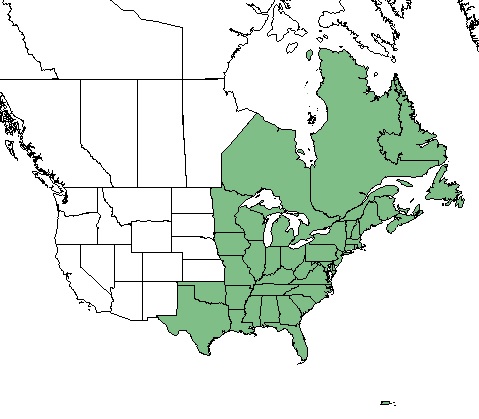

| Natural range of Osmundastrum cinnamomeum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common Name: cinnamon fern[1][2]

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: Osmunda cinnamomea Linnaeus[1]

Varieties: Osmunda cinnamomea var. cinnamomea; Osmunda cinnamomea Linnaeus var. glandulosa Waters; Osmundastrum cinnamomeum var. cinnamomeum; Osmundastrum cinnamomeum var. glandulosum (Waters) McAvoy[1]

Description

Osmunda cinnamomea is a perennial fern that grows as a forb/herb.[2] The leaves are dimorphic and equally broad through much of their length. The basal-most pinnae can be more than 1/2 as long as the largest pinnae. The photosynthetic pinnae have tufts of reddish hairs near the junction with the rachis.[1]

To distinguish from Anchistea virginica, look for a coarser texture, cinnamon tufts of tomentum in the axils of the pinnae, a greenish and fleshy rachis (vs. brown and wiry), and fronds clumped or tufted from a massive, woody, ascending rhizome covered with old petiole bases (vs. fronds borne scattered along a thick, horizontal, creeping rhizome).[1]

Sterile fronds increase their photosynthesis rates in the spring where they level off around 6-8 µmol m-2 s-1. Fertile fronds mature quicker and reached dark respiration rates 2-3 times greater than sterile fronds.[3]

Distribution

This species can be found from Newfoundland and Labrador westward to Ontario and Minnesota, southward to southern Florida and central Texas. It is also in Mexico, southward through Central America to northern South America, in the West Indies, and in eastern Asia.[4]

Ecology

Habitat

O. cinnamomeum occurs in bogs, peatlands, pocosins, wet savannas, floodplains, blackwater stream swamps,[4] swamps, marshes, and open and wet woods.[5] It is also found in disturbed areas including cutover swamps and roadsides.[6]

It increased its presence in response to soil disturbance by heavy silviculture in North Carolina longleaf pine sites.[7] It also increased its biomass in response to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in north Florida flatwoods forests.[8] It has shown regrowth in reestablished native habitat that was disturbed by these practices.[7][8]

Osmundastrum cinnamomeum is an indicator species for the North Florida Wet Flatwoods community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[9]

Phenology

In the southeastern and mid-Atlantic United States, O. cinnamomeum flowers from March through May.[4][10] On the Florida panhandle, the species has been observed flowering in April.[11]

Fire ecology

Populations of Osmundastrum cinnamomeum have been known to persist through repeated annual burning.[12]

Herbivory and toxicology

White-tailed deer are also reported to consume the fern.[13] The broad-winged hawk will collect sprigs for its nest of several plants and ferns, including O. cinnamomeum. These sprigs are likely used to maintain a clean lining for the nestling.[14]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

In China, fronds from O. cinnamomeum are cooked in stir-fry type dishes and consumed by people.[15] Previously in North America, the uncurled fronds were sought for their nutty flavor and would be cooked as a green with some dishes.[16]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 USDA NRCS (2016) The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 09 February 2018). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ Britton MR, Watkins Jr. JE (2016) The economy of reproduction in dimorphic ferns. Annals of Botany 118:1139-1149.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedWeakley 2015 - ↑ Correll DS (1938) A county check-list of Florida ferns and fern allies. American Fern Journal 28(1):11-16.

- ↑ Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University accessed using Southeastern Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) data portal. URL: http://sernecportal.org/portal/collections/index.php Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: Ida K. Langman and Louise F. A. Tanger. States and Counties: Pennsylvania: Lancaster and Monroe.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Cohen, S., R. Braham, and F. Sanchez. (2004). Seed Bank Viability in Disturbed Longleaf Pine Sites. Restoration Ecology 12(4):503-515.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 19 MAY 2021

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 9 FEB 2018

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Atwood EL (1941) White-tailed deer foods of the United States. The Journal of Wildlife Management 5(3):314-332.

- ↑ Heinrich B (2013) Why does a hawk build with green nesting material? Northeastern Naturalist 20(2):209-218.

- ↑ Liu Y, Wujisguleng W, Long C (2012) Food uses of ferns in China: A review. Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae 81(4):263-270.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.