Difference between revisions of "Nyssa sylvatica"

HaleighJoM (talk | contribs) (→Ecology) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{italic title}} | {{italic title}} | ||

| − | Common name: blackgum<ref name= "USDA Plant Database"/>, sour gum<ref name= | + | Common name: blackgum<ref name= "USDA Plant Database"/>, sour gum, pepperidge<ref name=weakley>Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.</ref> |

<!-- Get the taxonomy information from the NRCS Plants database --> | <!-- Get the taxonomy information from the NRCS Plants database --> | ||

{{taxobox | {{taxobox | ||

Revision as of 15:52, 16 June 2023

Common name: blackgum[1], sour gum, pepperidge[2]

| Nyssa sylvatica | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John Gwaltney at the Southeasten Flora Database | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Cornales |

| Family: | Cornaceae |

| Genus: | Nyssa |

| Species: | N. sylvatica |

| Binomial name | |

| Nyssa sylvatica Marshall | |

| |

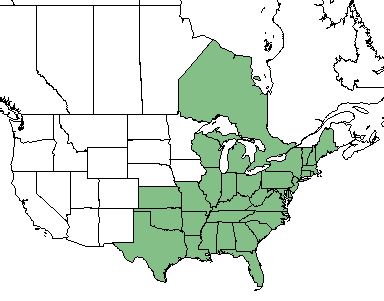

| Natural range of Nyssa sylvatica from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: none.[2]

Varieties: none.[2]

Description

N. sylvatica is a perennial tree of the Cornaceae family native to North America and Canada.[1]

N. sylvatica's fruit and flowers are pistillate and grow in 3-5 per peduncle. The fruit is 6-15 mm long and colored black-blue at maturity, with a rigid to smooth stone. The thin, pliable leaves are entire with irregular teeth near its acuminate apex. They are 18 cm long and 10 cm wide, being widest at the middle. The leaf petioles are 0.5-2.0 cm long. The bark is rough, divided by deep vertical and horizontal furrows into a pattern of squarish checks.[2]

Distribution

N. sylvatica ranges from southern Maine west to Michigan and southeast Wisconsin, south to central peninsular Florida, and west to eastern Texas and eastern Oklahoma.[2]

Ecology

Habitat

N. sylvatica proliferates in dry or mesic upland forests, less commonly in bottomlands, pine savannas, or upland depressions, where occasionally inundated briefly.[3] Specimens have been collected from residential areas, upland open woodlands, mixed upland hardwoods, creek floodplains, mesic wooded bluffs, flatwoods, lakeshores, river floodplain, live oak stands at cypress depressions, pond edges, slash pine flatwoods, wet hammocks, cypress-gum ponds, and pine woodlands.[4]

N. sylvatica has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished longleaf pinelands that were disturbed by agriculture in South Carolina, making it an indicator species for remnant woodlands.[5]

N. sylvatica had mixed responses to soil disturbance by improvement logging in Mississippi.[6] It also had variable changes in frequency in response to roller chopping and KG blade in east Texas pinewoods.[7] This species has shown regrowth, resistance to regrowth, or been unaffected by the reestablished native habitats that were disturbed by these practices.[6][7]

It does not respond to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.[8] Nyssa sylvatica is an indicator species for the North Florida Wet Flatwoods community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[9]

Phenology

N. sylvatica has been observed flowering April through June and fruiting August through October.[2]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates.[10]

Fire ecology

N. sylvatica is not fire resistant and has low fire tolerance;[1] despite this, populations on the Wade Tract in south Georgia have been known to persist through repeated annual burning.[11]

Herbivory and toxicology

Nyssa sylvatica has been observed to host aphids such as Aphis sp. (family Aphididae), leaf-footed bugs such as Leptoglossus oppositus (family Coreidae), treehoppers such as Telamona monticola (family Membracidae), plant bugs such as Plagiognathus albatus (family Miridae), and ground-nesting bees from the Andrenidae family such as Andrena atlantica and A. hippotes.[12] N. sylvatica has medium palatability to browsing animals.[1]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 USDA Plant Database https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=NYSY

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "weakley" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "weakley" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "weakley" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "weakley" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "weakley" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, R.K. Godfrey, Angus Gholson, Wilson Baker, Patricia Elliot, A.F. Clewell, E. Tyson, E.A. Hebb, H. Kurz, Richard Mitchell, D. B. Ward, W.G. D'Arcy, C. Monk, H. Larry Stripling, Elmar Prichard, R. Komarek, R. Jean, Kevin Oakes, Cecil Slaughter, Marc Minno, T. MacClendon, K. MacClendon, Tom Gilpin, William Platt, Richard Carter, W. Baker, Sidney McDaniel, Andre Clewell, Walter S. Judd, Bob Simmons, Dana Griffin, Bruce Hansen, JoAnn Hansen, R.F. Doren, Gwynn Ramsey, E.S. FOrd, P.L Redfearn, Richard Houk, William Lindsey, R. Kral, Robert Lazor, R. A> Norris, K. Craddock Burks, K.M. Meyer. States and counties: Florida (Liberty, Leon, Walton, Suwannee, Okaloosa, Wakulla, Jefferson, Jackson, Gadsden, Columbia, Bay, Alachua, Lake, Baker, Calhoun, Osceola, Clay, Washington, Dixie, Flagler, Franklin, Madison, St. Johns, Taylor, Volusia) North Carolina (Bladen) Georgia (Grady, Thomas, Grady) Tennessee (Macon)

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 McComb, W.C. and R.E. Noble. (1982). Response of Understory Vegetation to Improvement Cutting and Physiographic Site in Two Mid-South Forest Stands. Southern Appalachian Botanical Society 47(1):60-77.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Stransky, J.J., J.C. Huntley, and Wanda J. Risner. (1986). Net Community Production Dynamics in the Herb-Shrub Stratum of a Loblolly Pine-Hardwood Forest: Effects of CLearcutting and Site Preparation. Gen. Tech. Rep. SO-61. New Orleans, LA: U.S. Dept of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Forest Experiment Station. 11 p.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]