Difference between revisions of "Ilex opaca"

(→Taxonomic notes) |

(→Taxonomic notes) |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

==Taxonomic notes== | ==Taxonomic notes== | ||

| − | Synonyms: ''Ilex opaca'' var. ''opaca'' | + | Synonyms: ''Ilex opaca'' var. ''opaca''<ref name=weakley/> |

Varieties: none<ref name=weakley/> | Varieties: none<ref name=weakley/> | ||

Revision as of 13:46, 2 June 2023

| Ilex opaca | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Rebekah D. Wallace, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Celastrales |

| Family: | Aquifoliaceae |

| Genus: | Ilex |

| Species: | I. opaca |

| Binomial name | |

| Ilex opaca Aiton | |

| |

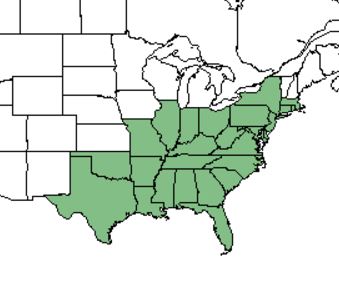

| Natural range of Ilex opaca from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: American holly, Christmas holly[1]

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Ilex opaca var. opaca[1]

Varieties: none[1]

Description

I. opaca is a upright evergreen tree that is commonly known as the Christmas holly. It is the only native holly in the U.S. to have spiny green, leathery leaves and bright red berries.[2] It's also the only Ilex species in the southern United States to become a medium to large tree.[1] The fine-textured wood is ideal for inlays in cabinetwork, carvings and vanier.[3]

“Trees or shrubs, usually with imperfect flowers. Leaves simple, entire, serrate, dentate or crenate; stipules obsolete. Flowers axillary, solitary, fascicled or in cymes, 4-7 merous, 4-8 mm broad; petals united at the base, imbricate in bud; pistillate flowers usually with nonfunctional stamens; anthers opening lengthwise; stigmas 4-7, essentially sessile. Drupe red, black or rarely yellow or white. Seeds with hard, bony endocarp (pyrenes), often grooved or ribbed on the back, 4-7 in a fruit, 1 in each locule.”[4]

"Medium or large tree, usually with a columnar or conical growth form, twigs minutely pubescent, glabrate. Leaves coriaceous, evergreen, dull above, elliptic to elliptic-obovate, 4-10 cm long, 2-5 cm wide, dentate with few to many sharp spine-tipped teeth or sometimes entire with only a single apical spine, revolute. Pedicels usually densely canescent. Staminate flowers in axillary, pedunculate, simple or compound cymes; sepals 4; petals 4, white; stamens 4. Pistillate flower 1-3 (when 3, in a simple cyme) in leaf axils or at nodes just below the leaves; sepals 4; petal 4 white; stamens 4. Drupe red or orange, rarely yellow, usually dull, globose or slightly ellipsoid, 0,7-1.2 cm long; pyrenes 4, irregularly grooved on the back, 6-7 mm long."[4]

Distribution

The northern range of this plant begins in Massachusetts, extends west to Illinois, Missouri, and Oklahoma, and south to peninsular Florida and Texas.[1]

Ilex opaca var. arenicola is endemic to central peninsular Florida to the Lake Wales Ridge area.[5]

Ecology

Habitat

Ideal habitats are moist, acidic, well-drained soils such as mesic hammocks, sand pine-oak woods, bordering floodplains, deciduous woodlands on limestone, and mesic steepheads (FSU Herbarium). Soils include sandy loam, loam, and medium loam; however, does not favor well in clay.[3][6]

I. opaca has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished South Carolina coastal plain communities that were disturbed by agriculture, making it an indicator species for remnant woodlands.[7] I. opaca was found to increase its presence in response to soil disturbance by heavy silvilculture in North Carolina. It has shown regrowth in reestablished longleaf pinelands that were disturbed by these practices.[8]

Associated species include Pinus taeda, P. echinata, P. glabra, Quercus hemisphaerica, Q. nigra, Q. incana, Q. virginiana, Cornus florida, Liquidambar styraciflua, Magnolia grandiflora, Sassafras albida, Vaccinium arboretum and V. stamineum.[6]

Phenology

I. opaca has been observed flowering from February through July with peak inflorescence in April.[9][6] This is a dioecious species, with separate male and female plants. The flowers of both sexes retain both male and female reproductive organs, however, only one is reproductively functional. Female flowers open synchronously, with each flower only lasting a day; while males open flower buds asynchronously throughout the season, with these flowers typically lasting 3 to 4 days. The fecundity of the female flowers is constrained by pollinator service, light, nutrient and water levels. Flowers are borne on the green stems of the new year's growth and can be seen March through July. The fruit is a red drupe containing four pyrenes.[10]

Seed dispersal

The fruit is a four-seeded drupe that is dispersed by birds and small mammals.[11] Large winter-migrating flocks of small birds such as cedar waxwing and American goldfinch, are one of the most important seed dispersal mechanisms for this species.[11]

Seed bank and germination

Germination is epigeal and very slow, usually requiring 16 months to 3 years. Overwinter storage or cold, moist stratification improves germination rates.[11] Carr (1991) showed that embryonic development in vitro is suppressed by light.

Fire ecology

I. opaca is very susceptible to fire and is typically absent from regularly or even occasionally burned forest. The bark is easily injured by fire and large trees may be killed by light fires in the understory.[11]

Pollination

Ilex opaca var. arenicola has been observed at the Archbold Biological Station to host leafcutting bees such as Megachile petulans (family Megachilidae), bees from the Apidae family such as Apis mellifera and Bombus impatiens, plasterer bees from the Colletidae family such as Colletes banksi and C. brimleyi, sweat bees from the Halictidae family such as Augochloropsis metallica and Augochloropsis sumptuosa, plasterer bees such as Pachodynerus erynnis (family Vespidae), as well as thread-waisted bees from the Sphecidae family such as Cerceris rozeni, Gorytes dorothyae ruseolus, Hoplisoides denticulatus denticulatus, H. placidus placidus, Liris argentata, L. muesebecki, Pseudoplisus smithii floridanus, Tachysphex apicalis, T. similis and Tanyoprymnus moneduloides.[12] Additionally, I. opaca has been observed to host ground-nesting bees from the Andrenidae family such as Andrena alleghaniensis, A. atlantica, A. cressonii, A. hilaris, A. imitatrix, A. miserabilis, A. nasonii, A. nuda, A. rehni, A. spiraeana, and A. vicina, as well as bees from the Melissodes communis (family Apidae), plasterer bees from the Colletidae family such as Colletes thoracicus and Hylaeus modestus, sweat bees from the Halictidae family such as Lasioglossum bruneri, L. cressonii, L. versans, Sphecodes aroniae and S. ranunculi, leafcutting bees such as Megachile xylocopoides (family Megachilidae), and plant bugs such as Nesiomiris hawaiiensis (family Miridae).[13]

Herbivory and toxicology

Cavities of I. opaca provide nesting habitat for the red-cockaded woodpecker.[14] Groves provide shelter to red-eyed towhee, bluebirds, cardinals, white throated sparrow, and robins.[15] The spines on the leaves are used as a defense against herbivory (Ehrlich and Raven 1967).

Diseases and parasites

It is susceptible to many different diseases such as: 14 species of leaf spot fungi, 6 species of black mildews, 2 powdery mildews, leaf drop, leaf scorch, and chlorosis.[2] Many insects also plague I. opaca such as: the southern red mite, which reduces the leaf and twig growth; the native holly leaf miner which causes leaves to drop prematurely; and the holly midge, which feeds on the berries hindering them from turning red.[11]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

I. opaca is closely associated with Christmas and in the past has been threatened by over harvesting for Christmas decoration.[11]

Medicinally, a decoction made from the fruits, bark, and alcohol was used to treat constipation, worms, coughs, pleurisy, fever, gout, rheumatism, and tumors. When the root bark was used for the decoction, it could treat colds, coughs, and tuberculosis.[16]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

Forrester, J. A. and D. J. Leopold (2006). "Extant and Potential Vegetation of an Old-Growth Maritime Ilex opaca Forest." Plant Ecology 183(2): 349-359

Gargiullo, M. B. and E. W. Stiles (1993). "Development of Secondary Metabolites in the Fruit Pulp of Ilex opaca and Ilex verticillata." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 120(4): 423-430.

Supnick, M. (1983). "On the Function of Leaf Spines in Ilex opaca." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 110(2): 228-230.

Supnick, M. (1985). "The Mean Inner Radius of Sun and Shade Ilex opaca Leaves." American Journal of Botany 72(9): 1490-1491

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "weakley" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "weakley" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 2.0 2.1 [[1]] Missouri Botanical Garden Accessed: January 6, 2016

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 [[2]]Accessed: January 6, 2016

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 679-81. Print.

- ↑ Sorrie, B. A. and A. S. Weakley 2001. Coastal Plain valcular plant endemics: Phytogeographic patterns. Castanea 66: 50-82.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: January 2016. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, W.W. Ashe, Tom Barnes, Leonard J. Brass, A.F. Clewell, K. Craddock Burks, S. Clawson, George R. Cooley, G. Fleming, P. Genelle, J.P. Gillespie, Robert K. Godfrey, Bruce Hansen, P. Hilsenbeck, R. Hilsenbeck, Walter S. Judd, Gary R. Knight, R. Komarek, R. Kral, H. Kurz, O. Lakela, Lloyd, James B. McFarlin, Lionel Melvin, Marc Minno, Richard S. Mitchell, J. Poppleton, Gwynn W. Ramsey, Paul Redfearn, George Reed, George Robinson, H. Shinners, A.G. Shuey, Cecil R. Slaughter, Robert F. Thorne, Kenneth A. Wilson, Carroll E. Wood, R. Wunderlin, and T. Wunderlin. States and Counties: Florida: Baker, Bay, Citrus, Columbia, Dixie, Escambia, Franklin, Gadsden, Highlands, Jackson, Jefferson, Lake, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Marion, Okaloosa, Orange, Polk, Santa Rosa, Suwannee, Volusia, Wakulla, Walton. Georgia: Grady.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Cohen, S., R. Braham, and F. Sanchez. (2004). Seed Bank Viability in Disturbed Longleaf Pine Sites. Restoration Ecology 12(4):503-515.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 12 DEC 2016

- ↑ Carr, D. E. (1991). "Sexual Dimorphism and Fruit Production in a Dioecious Understory Tree, Ilex opaca Ait." oecologia 85(3): 381-388.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 [[3]] Accessed: January 6, 2016

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [4]

- ↑ [[5]]Accessed: January 6, 2016

- ↑ Petrides, G. A. (1942). "Ilex opaca as a Late Winter Food for Birds." The Auk 59(4): 581-581.

- ↑ Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.