Difference between revisions of "Smilax smallii"

HaleighJoM (talk | contribs) (→Ecology) |

HaleighJoM (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

<!--===Pollination===--> | <!--===Pollination===--> | ||

| − | + | ===Herbivory and toxicology=== <!--Common herbivores, granivory, insect hosting, poisonous chemicals, allelopathy, etc--> | |

''S. smallii'' comprises 5-10% of the diets of large mammals, small mammals, and terrestrial birds.<ref name="Miller & Miller 1999">Miller JH, Miller KV (1999) Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.</ref> Larger mammals can include deer and cattle.<ref name="Thill 1984">Thill RE (1984) Deer and cattle diets on Louisiana pine-hardwood sites. The Journal of Wildlife Management 48(3):788-798.</ref> | ''S. smallii'' comprises 5-10% of the diets of large mammals, small mammals, and terrestrial birds.<ref name="Miller & Miller 1999">Miller JH, Miller KV (1999) Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.</ref> Larger mammals can include deer and cattle.<ref name="Thill 1984">Thill RE (1984) Deer and cattle diets on Louisiana pine-hardwood sites. The Journal of Wildlife Management 48(3):788-798.</ref> | ||

<!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | <!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | ||

Latest revision as of 17:09, 15 July 2022

| Smilax smallii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John Gwaltney hosted at Southeastern Flora.com | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida - Moncots |

| Order: | Liliales |

| Family: | Smilacaceae |

| Genus: | Smilax |

| Species: | S. smalliis |

| Binomial name | |

| Smilax smallii Morong | |

| |

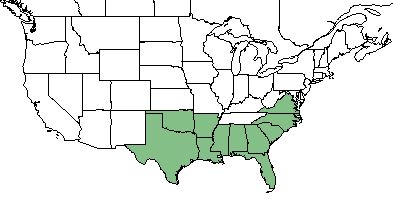

| Natural range of Smilax smallii from USDA NRCS [1]. | |

Common Name(s): Jackson-briar;[1] lanceleaf greenbrier;[2] southern smilax; jacksonvine[3]

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonym(s): S. maritima;[1] S. domingensis; S. lanceolata[2]

Description

Smilax smallii is a monoecious perennial that grows as a shrub or vine.[2] Leaves are small, light-green, shiny, and evergreen. Flowers are small, yellowish, and in clusters. Berries will remain a dull, brick red color for long periods of time before turning a dark reddish brown at maturity.[3] Pedicels are unequal and range from 1-4 in (2.5-10.2 cm).[4] Stems typically lack spines and occur at right angles to the main stem.[3] This plant can reach lengths of 6-12 ft (1.83-3.66 m).[3][4]

Distribution

This species primarily occurs on the coastal plain from Virginia, south to central peninsular Florida, westward to Texas.[1][2] It can also be found in Puerto Rico.[2]

Ecology

Habitat

S. smallii has been found in Longleaf Pine forests, titi thickets, upland pinelands, river floodplains, mesic wooded ravine slopes, dirt mounds, flatwoods, Cypress pond edges, and bottomland woodlands.[5] It is also found in disturbed areas including burned upland pinelands, roadsides, edges of dirt roads, and burned savannas.[5] S. smallii can be found in bottomland forests[1] and prefers moist alluvial acidic soils[3] and is drought tolerant.[6]

Associated species: Passiflora lutea, Smilax tamnoides, S. bona-nox, and Sageretia minutiflora.[5]

Smilax smallii is an indicator species for the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[7]

Phenology

S. smallii has been observed flowering May through July[1][8] and fruits from April to June of the following year.[1] A study in Florida, reported flowering in June and fruiting from February through July.[9]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates.[10]

Fire ecology

Populations of Smilax smallii have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[11][12][13]

Herbivory and toxicology

S. smallii comprises 5-10% of the diets of large mammals, small mammals, and terrestrial birds.[14] Larger mammals can include deer and cattle.[15]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

S. smallii is sometimes used in landscaping projects. However, since the species is not widely cultured, some contractors will collect samples locally. This has the potential to negatively impact populations if the species popularity continues to increase, especially in times of drought, pest outbreaks, or disease outbreaks where native species are more apt to prosper.[6]

Propagation can occur via root divisions, seeds, semi-hardwood cuttings, and softwood cuttings.[3] However, more research on propagation techniques are needed.[6]

Cultural use

There are many species of Smilax and it is thought they can all be used in similar ways. Historically, the roots were harvested and prepared in a red flour or a thick jelly that could be used in candies and sweet drinks. Our first known written account of using the plant roots to make this jelly is from the journal of Captain John Smith in 1626. Other travelers throughout US history have made note of the uses of Smilax plants. We know the flour was used in breads and soups, and that a drink very similar to Sarsaparilla could be prepared.[16]

Humans have also utilized this species in decorations, landscaping, and as a source of food, consuming tubers and new spring growth.[6]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Weakley AS (2015) Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 USDA NRCS (2016) The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 22 January 2018). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Plant database: Smilax smallii. (22 January 2018) Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. URL: https://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=SMSM

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Morong T (1894) The Smilaceae of North and Central America. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 21(10):419-443.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Florida State University Herbarium Database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: Robert K. Godfrey, S. Greeter, Roy Komarek, R. Kral, John B. Nelson, James D. Ray Jr., John W. Thieret, and Roomie Wilson. States and counties: Alabama: Henry and Mobile. Florida: Leon. Georgia: Grady and Thomas. Louisiana: Sabine and Washington. Mississippi: Lowndes. South Carolina: Calhoun.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Davis BE, Chappell MR, Schwevens JD (2012) Using native plants in traditional design contexts: Smilax smallii provides an example. 13(1):27-34.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 22 JAN 2018

- ↑ Skeate ST (1987) Interactions between birds and fruits in a northern Florida hammock community. Ecology 68(2):297-309.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Miller JH, Miller KV (1999) Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Thill RE (1984) Deer and cattle diets on Louisiana pine-hardwood sites. The Journal of Wildlife Management 48(3):788-798.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.