Difference between revisions of "Pteridium aquilinum"

HaleighJoM (talk | contribs) (→Ecology) |

|||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | Common names: | + | Common names: brackenfern, lacy bracken, tropical bracken, tailed bracken, eastern bracken, southern bracken |

==Taxonomic notes== | ==Taxonomic notes== | ||

Subspecies: ''Pteridium aquilinum ssp. latiusculum'', ''Pteridium aquilinum ssp. pseudocaudatum'' | Subspecies: ''Pteridium aquilinum ssp. latiusculum'', ''Pteridium aquilinum ssp. pseudocaudatum'' | ||

Revision as of 15:48, 14 July 2023

| Pteridium aquilinum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Tracheophyta- Vascular plants |

| Class: | Polypodiopsida - Leptosporangiate ferns |

| Order: | Polypodiales |

| Family: | Dennstaedtiaceae |

| Genus: | Pteridium |

| Species: | P. aquilinum |

| Binomial name | |

| Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn | |

| |

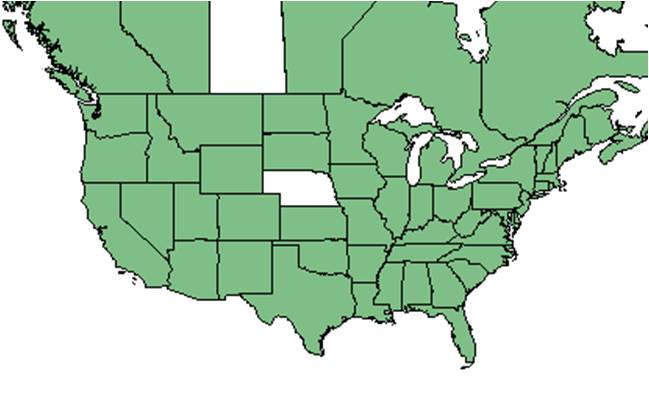

| Natural range of Pteridium aquilinum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: brackenfern, lacy bracken, tropical bracken, tailed bracken, eastern bracken, southern bracken

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Subspecies: Pteridium aquilinum ssp. latiusculum, Pteridium aquilinum ssp. pseudocaudatum

Description

A description of Pteridium aquilinum is provided in The Flora of North America.

Pteridium aquilinum does not have specialized underground storage units apart from its rhizomes.[1] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an non-structural carbohydrate concentration of 321.5 mg/g (ranking 13 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 41.7% (ranking 54 out of 100 species studied).[1]

Distribution

Ecology

Habitat

P. aquilinum has been found in forested swamps, slash pine forests, limerock, and pinelands.[2] It is also found in disturbed areas such as powerline corridors.[2] Associated species: Gaultheria shallon, Rubus, parviflorus, Cirsium canadense, Hypericum perfoliatum, Achillea millefolium, Anaphalis margaritacea, Leucanthemum vulgare, Prunella vulgaris, Hypochaeris radicata, and Juncus.[2]

Pteridium aquilinum is restricted to native groundcover with a statistical affinity in upland pinelands of South Georgia.[3]

P. aquilinum reduced its occurrence in response to agricultural soil disturbance in South Carolinian old growth longleaf forests.[4] It has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished longleaf habitat that was disturbed by agricultural practices, making it a remnant woodland indicator species.[5] It became absent in response to soil disturbance by military training in west Georgia longleaf pine forests.[6] This species also became absent or decreased its occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in southwest Georgia.[7][8][3] It has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished native habitats that were disturbed by these practices.

This species had a mixed response to soil disturbance by clearcutting and roller chopping in north Florida. Foliar cover was often dependent on time since disturbance.[9]

P. aquilinum increased its biomass in response to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in north Florida flatwoods forests. It has shown regrowth in reestablished flatwoods that were disturbed by these practices.[10]

Pteridium aquilinum is frequent and abundant in the North Florida Longleaf Woodlands, Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands, Panhandle Silty Longleaf Woodlands, and Upper Panhandle Savannas community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[11]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by wind.[12]

Fire ecology

Populations of Pteridium aquilinum have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[13]

Herbivory and toxicology

Pteridium aquilinum has been observed to host leafhoppers such as Colladonus sp. (family Cicadellidae).[14]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Native Americans would use this plant to treat urinary problems, stomach cramps, and mastitis. The plant could also be used to treat intestinal worms and diarrhea.[15] The young fresh shoots of the plant can be cooked as a green, and uncooked stalks have a juice that can be used as a relish or chewed on like gum. In New Zealand and Japan it is very commonly used in dishes, but is not as common in the United States.[16]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Florida State University Herbarium Database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: Robert K. Godfrey, Richard S. Mitchell, Katelin D. Pearson. States and counties: Florida: Collier, Dade, Monroe. Oregon: Multnomah.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Ostertag, T.E., and K.M. Robertson. 2007. A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, South Georgia, USA. Pages 109–120 in R.E. Masters and K.E.M. Galley (eds.). Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.

- ↑ Hedman, C.W., S.L. Grace, and S.E. King. (2000). Vegetation composition and structure of southern coastal plain pine forests: an ecological comparison. Forest Ecology and Management 134:233-247.

- ↑ Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.

- ↑ Lewis, C.E., G.W. Tanner, and W.S. Terry. (1988). Plant responses to pine management and deferred-rotation grazing in north Florida. Journal of Range Management 41(6):460-465.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- ↑ Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.