Difference between revisions of "Phytolacca americana"

Krobertson (talk | contribs) (→Ecology) |

Krobertson (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

===Pollination and use by animals=== | ===Pollination and use by animals=== | ||

| − | ''Phytolacca americana'' has been observed at the Archbold Biological Station to host bees | + | ''Phytolacca americana'' has been observed at the Archbold Biological Station to host bees the bumblebee ''Bombus impatiens'' (family Apidae), leafcutting bee ''Heriades leavitti'' (family Megachilidae), sweat bees from the Halictidae family ''Augochlora pura, Augochlorella striata, Augochloropsis metallica, A. sumptuosa, Lasioglossum lepidii, L. miniatulus, L. nymphalis, L. pectoralis, L. placidensis,'' and ''L. puteulanum'', thread-waisted wasps from the Sphecidae family ''Ectemnius maculosus, E. rufipes ais, Isodontia exornata,'' and ''Oxybelus laetus fulvipes'', as well as wasps from the Vespidae family ''Leptochilus alcolhuus, L. republicanus, Polistes dorsalis hunteri,'' and ''Zethus slossonae''.<ref name="Deyrup 2015">Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.</ref> Additionally, ''P. americana'' has been observed to host bees from the Apidae family such as ''Apis mellifera'' and ''Ceratina dupla'', sweat bees from the Halictidae family such as ''Lasioglossum ephialtum'', ''L. oceanicum'', and ''L. pilosum'', and leafhoppers from the Pleosporaceae family such as ''Cicadellidae sp.'' and ''Vespidae sp.''.<ref>Discoverlife.org [https://www.discoverlife.org/20/q?search=Bidens+albaDiscoverlife.org|Discoverlife.org]</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | ''Phytolacca americana'' is poisonous to cattle and sheep, and occasionally is poisonous to horses, goats, and pigs. The entire green plant is toxic, but the roots are more toxic. It is a gastrointestinal irritant. It causes abdominal pain, vomiting, and purging. There may be convulsions and death usually due to respiratory failure.<ref name=sperry>Sperry, O.E., J.W. Dollahite, G.O. Hoffman, and B.J. Camp. 1965. Texas plants poisonous to livestock. Texas A&M University, Texas Agricultural Experiment Station, Texas Agricultural Extension Service. College Station, Texas.<ref/><ref name = hardin>Hardin, J.W. 1961. Poisonous plants of North Carolina. Agricultural Experiment Station, North Carolina State College, Raleigh, North Carolina. Bulletin 414. 128 p.</ref> | ||

<!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | <!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | ||

| Line 55: | Line 57: | ||

People in Appalachia would eat and can the immature leaves of the pokeberry plant<ref> Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.</ref>, and the young shoots can be used an asparagus or spinach substitute. Care must be taken not to harvest mature plants because the bark will be toxic. The berries can also be used as a food coloring in frosting and candy.<ref> Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.</ref> | People in Appalachia would eat and can the immature leaves of the pokeberry plant<ref> Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.</ref>, and the young shoots can be used an asparagus or spinach substitute. Care must be taken not to harvest mature plants because the bark will be toxic. The berries can also be used as a food coloring in frosting and candy.<ref> Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Leaves can be eaten as greens, but in the cooking process the water should be changed twice to avoid toxic effects.<ref name = hardin/> | ||

==Photo Gallery== | ==Photo Gallery== | ||

Revision as of 16:50, 3 January 2022

| Phytolacca americana | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Karan A. Rawlins, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Caryophyllales |

| Family: | Phytolaccaceae |

| Genus: | Phytolacca |

| Species: | P. americana |

| Binomial name | |

| Phytolacca americana L. | |

| |

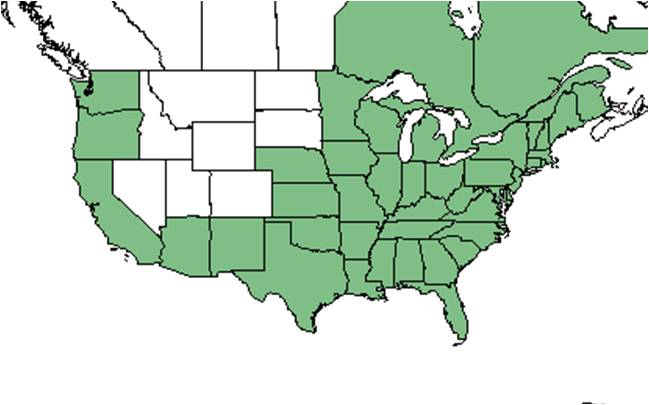

| Natural range of Phytolacca americana from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: American pokeweed; Common pokeweed; Poke; Pokeberry[1]

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: none.[1]

Description

A description of Phytolacca americana is provided in The Flora of North America. It is a robust, perennial herb that grows 1-3 m tall. The roots are thick and fleshy. The leaves have an alternate pattern, glabrous texture, entire margin, and lanceolate to elliptic shape. They grow 3-12 cm wide and 8-30 cm long with a rounded base. The petioles are 1-5 cm long. Racemes are 5-20 cm with bracteate pedicels. The flowers are perfect, colored green to white, and 2-3 mm long. They include 5 sepals, 5-30 stamens, and a superior ovary. The berries are 5-12 carpellate, purplish-black, 4-6 mm long, and 7-10 mm in diameter. The seeds are lustrous black, 2.5-3 mm long, and flattened.[1]

Distribution

This plant is an abundant native weed that occurs throughout eastern North America.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

P. americana has been found in hydric hammocks, swamp edges, coral limestone, sandbars, mangrove swamps, and floodplain forests.[2] It is also found in disturbed areas including disturbed coastal hammocks, along canals, farmlands, orange groves, landfills, burned longleaf pine-wiregrass flatwoods, pine-hickory camping woods, and along roadsides.[2] Associated species: Sabal, Quercus, Elaphrium, Swietenia, Dalbergia, Gouania, and Schinus.[2]

Phenology

This plant has been observed to flower from March through November, with peak inflorescence in May through July.[1][3]

Seed dispersal

P. americana is dispersed primarily by birds that eat the berries and deposit them through defication.[4] It has been found to be dispersed by germinating from the carrion of pigs that ingested it.[5]

Fire ecology

Populations of Phytolacca americana have been known to persist through repeated annual burning.[6]

Pollination and use by animals

Phytolacca americana has been observed at the Archbold Biological Station to host bees the bumblebee Bombus impatiens (family Apidae), leafcutting bee Heriades leavitti (family Megachilidae), sweat bees from the Halictidae family Augochlora pura, Augochlorella striata, Augochloropsis metallica, A. sumptuosa, Lasioglossum lepidii, L. miniatulus, L. nymphalis, L. pectoralis, L. placidensis, and L. puteulanum, thread-waisted wasps from the Sphecidae family Ectemnius maculosus, E. rufipes ais, Isodontia exornata, and Oxybelus laetus fulvipes, as well as wasps from the Vespidae family Leptochilus alcolhuus, L. republicanus, Polistes dorsalis hunteri, and Zethus slossonae.[7] Additionally, P. americana has been observed to host bees from the Apidae family such as Apis mellifera and Ceratina dupla, sweat bees from the Halictidae family such as Lasioglossum ephialtum, L. oceanicum, and L. pilosum, and leafhoppers from the Pleosporaceae family such as Cicadellidae sp. and Vespidae sp..[8]

Phytolacca americana is poisonous to cattle and sheep, and occasionally is poisonous to horses, goats, and pigs. The entire green plant is toxic, but the roots are more toxic. It is a gastrointestinal irritant. It causes abdominal pain, vomiting, and purging. There may be convulsions and death usually due to respiratory failure.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Historically, the roots and berry juice was used by native peoples to treat skin cancers, diseases, swelling, and injuries.[9] The root can be extremely toxic and act as a narcotic, emetic, and cathartic if ingested in too large of doses.[10]

People in Appalachia would eat and can the immature leaves of the pokeberry plant[11], and the young shoots can be used an asparagus or spinach substitute. Care must be taken not to harvest mature plants because the bark will be toxic. The berries can also be used as a food coloring in frosting and candy.[12]

Leaves can be eaten as greens, but in the cooking process the water should be changed twice to avoid toxic effects.[13]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Florida State University Herbarium Database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, George R. Cooley, R. J. Eaton, D. L. Fichtner, Robert K. Godfrey, B. K. Holst, O. Lakela, S. W. Leonard, Marc Minno, Grady W. Reinert, Cecil R Slaughter, S. D. Todd, and Jean W. Wooten. States and counties: Florida: Hernando, Indian River, Jefferson, Leon, Liberty, Manatee, Monroe, Okaloosa, Orange, and Sarasota.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 19 MAY 2021

- ↑ Michigan State University Department of Plant, Soil, and Microbial Biology. Common Pokeweed. https://www.canr.msu.edu/weeds/extension/common-pokeweed

- ↑ Tomberlin, J. K., Barton, B. T., Lashley, M. A., & Jordan, H. R. (2017). Mass mortality events and the role of necrophagous invertebrates. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 23, 7-12.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- ↑ Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.

- ↑ Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedhardin