Difference between revisions of "Desmodium viridiflorum"

(→Ecology) |

|||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ||

| − | According to Hendricks' study, ''Desmodium viridiflorum'' was noticeably more abundant in burned plots | + | According to Hendricks' study, ''Desmodium viridiflorum'' was noticeably more abundant in burned plots,<ref name=h99/> and populations have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.<ref>Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.</ref> In the Oconee National Forest, the plots had a history of no burning, there were 28 individuals (of ''Desmodium viridiflorum'') per ha.<ref name=h99/> In the Piedmont National Wildlife Refuge, the plots were burned in the dormant season (winter) every 4-5 years, there were 2,563 to 3,953 individuals (of ''Desmodium viridiflorum'') per ha.<ref name=h99/> Areas that are burned more frequently are more likely to have established populations of ''D. viridiflorum'' and will be persistent and large enough to affect nitrogen availability.<ref name=h99/> In drought conditions, water stress is suggested by Hendricks and that the stress contributes to loss of leaf area, which in turn, reduces the photosynthate available to maintain the high nitrogen fixing rates. <ref name=h99/> |

<!--===Pollination and use by animals===--> <!--Herbivory, granivory, insect hosting, etc.--> | <!--===Pollination and use by animals===--> <!--Herbivory, granivory, insect hosting, etc.--> | ||

<!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | <!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | ||

Revision as of 19:52, 19 July 2021

| Desmodium viridiflorum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae ⁄ Leguminosae |

| Genus: | Desmodium |

| Species: | D. viridiflorum |

| Binomial name | |

| Desmodium viridiflorum (L.) DC. | |

| |

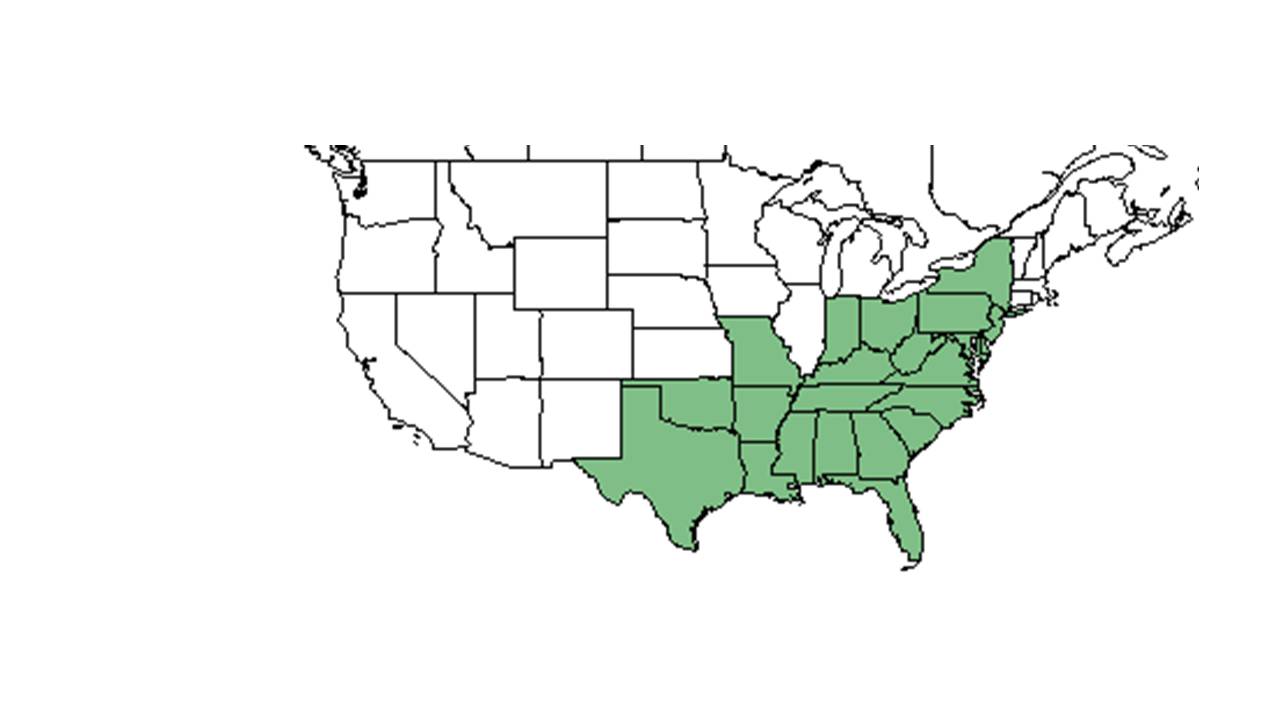

| Natural range of Desmodium viridiflorum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Velvetleaf tick-trefoil

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonym: Meibomia viridiflora (Linnaeus) Kuntze.[1]

Varieties: none.[1]

Description

Generally, for Desmodium genus, they are "annual or perennial herbs, shrubs or small trees. Leaves 1-5 foliolate, pinnately 3-foliolate in ours or rarely the uppermost or lowermost 1-foliolate; leaflets entire, usually stipellate; stipules caduceus to persistent, ovate to subulate, foliaceous to setaceous, often striate. Inflorescence terminal and from the upper axils, paniculate or occasionally racemose; pedicel of each papilionaceous flower subtended by a secondary bract or bractlet, the cluster of 1-few flowers subtended by a primary bract. Calyx slightly to conspicuously 2-lipped, the upper lip scarcely bifid, the lower lip 3-dentate; petals pink, roseate, purple, bluish or white; stamens monadelphous or more commonly diadelphous and then 9 and 1. Legume a stipitate loment, the segments 2-many or rarely solitary, usually flattened and densely uncinated-pubescent, separating into 1-seeded, indehiscent segments." [2]

Specifically, for D. viridiflorum species, they are "erect perennial; stems 0.8-2 m tall, sparsely to densely-puberulent as well as uncinlate-pubescent, occasionally pilose. Terminal leaflets rhombic or deltoid, 3.5-11 cm long, usually 2/3 as wide as long, glabrate to moderately pilose above and densely velvety-tomentose beneath; stipules lance-ovate, acuminate, 3-7 mm long; stipels persistent. Inflorescence paniculate, densely puberulent and uncinlate-pubescent; pedicels 2.5-8 mm long. Calyx sparsely to densely short-pubescent; petals pinkish to rose, 5-9 mm long, 3.5-5 mm broad, straight or somewhat angled above and bluntly angular to somewhat rounded below, moderately to densely uncinulate-pubescent on both sides and sutures; stipe 2.5-6 mm long, considerably longer than calyx tube but shorter than stamina remnants." [2]

Distribution

It is distributed widely throughout the eastern U.S.. [3]

Ecology

It is a legume with a relatively high nitrogen-fixation rate and acetylene reduction rate.[4][5]

Habitat

In the southeastern coastal plain, this species is associated with open, frequently burned longleaf, shortleaf pine-oak-hickory, loblolly pine upland native and old-field communities and open upland hardwood forests (Ultisols).[5][6] It occurs in both native areas and in old-field habitats and areas with recent soil disturbance. It is found on loamy sands and sandy loams. Associated species include Desmodium floridanum, D. strictum, D. glabellum, D. paniculatum, and Pinus palustris.[6]

Desmodium viridiflorum is an indicator species for the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[7]

Phenology

In the southeastern coastal plain it flowers from July-September and fruits July-October.[6] In north Florida, D. viridiflorum has been observed flowering from July to October with peak inflorescence in September.[8]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by translocation on animal fur or feathers. [9]

Fire ecology

According to Hendricks' study, Desmodium viridiflorum was noticeably more abundant in burned plots,[4] and populations have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[10] In the Oconee National Forest, the plots had a history of no burning, there were 28 individuals (of Desmodium viridiflorum) per ha.[4] In the Piedmont National Wildlife Refuge, the plots were burned in the dormant season (winter) every 4-5 years, there were 2,563 to 3,953 individuals (of Desmodium viridiflorum) per ha.[4] Areas that are burned more frequently are more likely to have established populations of D. viridiflorum and will be persistent and large enough to affect nitrogen availability.[4] In drought conditions, water stress is suggested by Hendricks and that the stress contributes to loss of leaf area, which in turn, reduces the photosynthate available to maintain the high nitrogen fixing rates. [4]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 604-11. Print.

- ↑ NRCS Plants Database http://plants.usda.gov/java

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Hendricks, J. J. and L. R. Boring (1999). "N2-fixation by native herbaceous legumes in burned pine ecosystems of the southeastern United States." Forest Ecology and Management 113: 167-177.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Lajeunesse, S. D., J. J. Dilustro, et al. (2006). "Ground layer carbon and nitrogen cycling and legume nitrogen inputs following fire in mixed pine forests." American Journal of Botany 93: 84-93.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Tom Barnes, Ritchie Bell, Boothes, Loran C. Anderson, A.F. Clewell, R.K. Godfrey, Randy Haynes, Samuel B. Jones, R. Komarek, R. Kral, T. MacCleandon, Sidney McDaniel, R. A. Norris, A.E. Radford, Cecil R. Slaughter, V. Sullivan, and J. Wooten. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Franklin, Jackson, Leon, Liberty, Okaloosa, Putnam, Volusia, and Wakulla. Georgia: Grady and Gilmer. South Carolina: Marion. Mississippi: Hancock. Alabama: Cleburne. North Carolina: Davie.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 8 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.