Difference between revisions of "Sassafras albidum"

(→Cultural use) |

(→Ecology) |

||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

Sassafras prefers environments that are subject to spring burns. They will be abundant in understory that is burned in late winter and spring burns.<ref name="kush">Kush, J. S., et al. (1999). "Understory plant community response after 23 years of hardwood control treatments in natural longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) forests." Canadian Journal of Forest Research 29: 1047-1054.</ref> | Sassafras prefers environments that are subject to spring burns. They will be abundant in understory that is burned in late winter and spring burns.<ref name="kush">Kush, J. S., et al. (1999). "Understory plant community response after 23 years of hardwood control treatments in natural longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) forests." Canadian Journal of Forest Research 29: 1047-1054.</ref> | ||

<!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ===Pollination and use by animals=== |

| − | + | ''Sassafras albidum'' has been observed to host species such as ''Cedusa sp.'' (family Derbidae), ''Ormenoides venusta'' (family Flatidae), and members of the Cicadellidae family such as ''Eratoneura ardens, Graphocephala fennahi, G. coccinea, G. teliformis, Typhlocyba sp.'' and ''Ormenoides venusta''.<ref>Discoverlife.org [https://www.discoverlife.org/20/q?search=Bidens+albaDiscoverlife.org|Discoverlife.org]</ref> | |

| − | This species is a variety of ''Persea'' and sassafras that is a primary food for the Palamedes swallowtail caterpillar.<ref name="spiegel">Spiegel, K. S. and L. M. Leege (2013). "Impacts of laurel wilt disease on redbay (Persea borbonia (L.) Spreng.) population structure and forest communities in the coastal plain of Georgia, USA." Biological Invasions 15(11): 2467-2487.</ref> | + | The fruit produced by the tree is commonly eaten by animals who in turn disperse the seeds. Such animals include: quail, wild turkeys, kingbirds, crested flycatchers, mockingbirds, sapsuckers, pileated woodpeckers, yellowthroat warblers, and phoebes. Other animals will eat the fruit, bark and wood as well; black bears, beavers, rabbits, and squirrels. Deer will forage in the foliage.<ref name= "USDA"> [https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=CEAM USDA Plant Database]</ref> This species is a variety of ''Persea'' and sassafras that is a primary food for the Palamedes swallowtail caterpillar.<ref name="spiegel">Spiegel, K. S. and L. M. Leege (2013). "Impacts of laurel wilt disease on redbay (Persea borbonia (L.) Spreng.) population structure and forest communities in the coastal plain of Georgia, USA." Biological Invasions 15(11): 2467-2487.</ref> |

<!--Herbivory, granivory, insect hosting, etc.--> | <!--Herbivory, granivory, insect hosting, etc.--> | ||

===Diseases and parasites=== | ===Diseases and parasites=== | ||

| − | Insects will eat the entire leaves and the plants can develop root rot is they are in an environment with wet clay soil.<ref name= "USDA"> [https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=CEAM USDA Plant Database]</ref> | + | Insects will eat the entire leaves and the plants can develop root rot is they are in an environment with wet clay soil.<ref name= "USDA"> [https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=CEAM USDA Plant Database]</ref> Laurel wilt impacting sassafras has been recorded in the Atlantic Coastal Plain region that the species is found.<ref name= "mayfield">Mayfield, A. E. and J. L. Hanula (2012). "Effect of Tree Species and End Seal on Attractiveness and Utility of Cut Bolts to the Redbay Ambrosia Beetle and Granulate Ambrosia Beetle (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae)." Journal of Economic Entomology 105(2): 461-470.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | Laurel wilt impacting sassafras has been recorded in the Atlantic Coastal Plain region that the species is found.<ref name= "mayfield">Mayfield, A. E. and J. L. Hanula (2012). "Effect of Tree Species and End Seal on Attractiveness and Utility of Cut Bolts to the Redbay Ambrosia Beetle and Granulate Ambrosia Beetle (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae)." Journal of Economic Entomology 105(2): 461-470.</ref> | ||

==Conservation, cultivation, and restoration== | ==Conservation, cultivation, and restoration== | ||

Revision as of 12:49, 18 June 2021

Common Names: Nees sassafras[1], cinnamon wood, smelling stick, ague tree[2]

| Sassafras albidum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Chris Evans, University of Illinois, Bugwood.org hosted at Forestryimages.org | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Laurales |

| Family: | Lauraceae |

| Genus: | Sassafras |

| Species: | S. albidum |

| Binomial name | |

| Sassafras albidum (Nutt.) Nees | |

| |

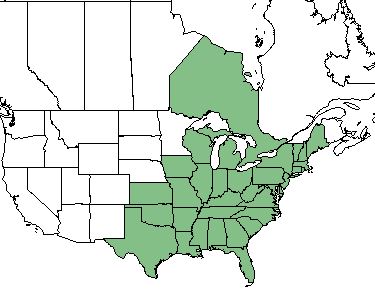

| Natural range of Sassafras albidum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonym: none

Variety: S. albidum var. molle (Rafinesque) Fernald

Description

S. albidum is a perennial shrub/tree of the Lauraceae family that is native to North America.[1]

Distribution

S. albidum is found throughout the eastern United States as far west as Texas and Kansas, as well as Ontario, Canada.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

Habitats for S. albidum include forests, old fields, disturbed areas and even fencerows.[3] The tree prefers low pH soils.[1] Specimens of this species have been taken from Moist loam at edges of woods, shaded mixed hardwoods region, fence rows, oak woodland, edge of orange groves, old foeld, river bluff, moist woods, limestone soil site, and a roadbank.[4] S. albidum exhibited no significant response to agricultural-based soil disturbance in South Carolina coastal plains communities.[5] S. albidum responds positively to soil disturbance by heavy silvilculture in North Carolina.[6] When exposed to soil disturbance by military training in West Georgia, S. albidum responds negatively by way of absence.[7]

Phenology

S. albidum has been observed to flower in March.[8]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates.[9]

Fire ecology

Sassafras prefers environments that are subject to spring burns. They will be abundant in understory that is burned in late winter and spring burns.[10]

Pollination and use by animals

Sassafras albidum has been observed to host species such as Cedusa sp. (family Derbidae), Ormenoides venusta (family Flatidae), and members of the Cicadellidae family such as Eratoneura ardens, Graphocephala fennahi, G. coccinea, G. teliformis, Typhlocyba sp. and Ormenoides venusta.[11]

The fruit produced by the tree is commonly eaten by animals who in turn disperse the seeds. Such animals include: quail, wild turkeys, kingbirds, crested flycatchers, mockingbirds, sapsuckers, pileated woodpeckers, yellowthroat warblers, and phoebes. Other animals will eat the fruit, bark and wood as well; black bears, beavers, rabbits, and squirrels. Deer will forage in the foliage.[1] This species is a variety of Persea and sassafras that is a primary food for the Palamedes swallowtail caterpillar.[12]

Diseases and parasites

Insects will eat the entire leaves and the plants can develop root rot is they are in an environment with wet clay soil.[1] Laurel wilt impacting sassafras has been recorded in the Atlantic Coastal Plain region that the species is found.[13]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

In the early 1800s the plant was used in a variety of treatments. Bronchitis, respiratory and digestive problems were treated with a tea from the root bark, and this same tea was used to slow milk production in nursing mothers, kidney problems, and dysentery. The bark was used as a poultice for treating sore eyes.[14]

The plant was famous for its possible medicinal uses and was used in root teas and gumbo. The bark could be dried and later eaten or then boiled with sugar to make sauce.[15]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 USDA Plant Database

- ↑ Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.

- ↑ Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: Loran Anderson, Kathy Craddock Burks, Gary R. Knight, R.K.Godfrey, Patricia Elliot, Sidney McDaniel, Richard S. Mitchell, Elmar C. Prichard, Lovett Williams Jr., H. Kurz, Gwynn W. Ramsey, H. Larry E. Stripling, Wayne R. Faircloth, M. Garland, Delzie Demaree, Kurt E. Blum, Gary H. Morton, Frank Bowers, Robert. L. Lazor, John Moore, H.A. Wahl, John W. Thieret, Michael Cartrett, R. F. Doren, Clarke Hudson, Norlan C. Henderson, W.J. Taylor, S.B. Jones, States and counties: Florida (Leon, Jefferson, Jackson, Liberty, Volusia, Madison, Washington, Gadsden, Franklin, Wakulla) Georgia (Brooks, Stewart, Thomas), Virginia (Smyth, Giles), Arkansas (Saline, St. Francis), Tennessee (Summer, Campbell, Davidson), West Virginia (Monroe), Louisiana (Tangipahoa, Claiborne, Caddo), North Carolina (Macon, Wake), Mississippi (Covington, Jasper, Pike, Giles), Missouri (McDonald, Iron), Maryland (Anne Arundel), Louisiana (Beauregard, Bienville, Madison), Alabama (Colbert), New Jersey (Weston, Somerset), Pennsylvania (Juniata), Indiana (Huntington, Newton, Huntington)

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.

- ↑ Cohen, S., R. Braham, and F. Sanchez. (2004). Seed Bank Viability in Disturbed Longleaf Pine Sites. Restoration Ecology 12(4):503-515.

- ↑ Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 29 MAY 2018

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Kush, J. S., et al. (1999). "Understory plant community response after 23 years of hardwood control treatments in natural longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) forests." Canadian Journal of Forest Research 29: 1047-1054.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- ↑ Spiegel, K. S. and L. M. Leege (2013). "Impacts of laurel wilt disease on redbay (Persea borbonia (L.) Spreng.) population structure and forest communities in the coastal plain of Georgia, USA." Biological Invasions 15(11): 2467-2487.

- ↑ Mayfield, A. E. and J. L. Hanula (2012). "Effect of Tree Species and End Seal on Attractiveness and Utility of Cut Bolts to the Redbay Ambrosia Beetle and Granulate Ambrosia Beetle (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae)." Journal of Economic Entomology 105(2): 461-470.

- ↑ Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.