Difference between revisions of "Vaccinium arboreum"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{italic title}} | {{italic title}} | ||

| − | Common names: farkleberry<ref name= "USDA"> [https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=CEAM USDA Plant Database]</ref>, sparkleberry<ref name="behm">Behm, A. L., et al. (2004). "Flammability of native understory species in pine flatwood and hardwood hammock ecosystems and implications for the wildland-urban interface." International Journal of Wildland Fire 13: 355-365.</ref>, winter huckleberry<ref name="blair">Blair, R. M. (1971). "Forage production after hardwood control in a southern pine-hardwood stand." Forest Science 17(3): 279-284.</ref>, tree sparkleberry<ref name= "bowman">Bowman, J. L., et al. (1999). Effects of red-cockaded woodpecker management on vegetative composition and structure and subsequent impacts on game species. Proceedings of the Fifty-third Annual Conference, Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. A. G. Wong, P. Doerr, D. Woodward, P. Mazik and R. Lequire. Greensboro, NC, Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies: 220-234.</ref>, tree huckleberry <ref name=";ay">Lay, D. W. (1956). "Effects of prescribed burning on forage and mast production in southern pine forests." Journal of Forestry 29(9): 582-584.</ref> | + | Common names: farkleberry<ref name= "USDA"> [https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=CEAM USDA Plant Database]</ref>, sparkleberry<ref name="behm">Behm, A. L., et al. (2004). "Flammability of native understory species in pine flatwood and hardwood hammock ecosystems and implications for the wildland-urban interface." International Journal of Wildland Fire 13: 355-365.</ref>, winter huckleberry<ref name="blair">Blair, R. M. (1971). "Forage production after hardwood control in a southern pine-hardwood stand." Forest Science 17(3): 279-284.</ref>, tree sparkleberry<ref name= "bowman">Bowman, J. L., et al. (1999). Effects of red-cockaded woodpecker management on vegetative composition and structure and subsequent impacts on game species. Proceedings of the Fifty-third Annual Conference, Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. A. G. Wong, P. Doerr, D. Woodward, P. Mazik and R. Lequire. Greensboro, NC, Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies: 220-234.</ref>, tree huckleberry<ref name=";ay">Lay, D. W. (1956). "Effects of prescribed burning on forage and mast production in southern pine forests." Journal of Forestry 29(9): 582-584.</ref> |

<!-- Get the taxonomy information from the NRCS Plants database --> | <!-- Get the taxonomy information from the NRCS Plants database --> | ||

{{taxobox | {{taxobox | ||

Revision as of 12:30, 13 May 2021

Common names: farkleberry[1], sparkleberry[2], winter huckleberry[3], tree sparkleberry[4], tree huckleberry[5]

| Vaccinium arboreum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John Hilty hosted at IllinoisWildflowers.info | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Ericales |

| Family: | Ericaceae |

| Genus: | Vaccinium |

| Species: | V. arboreum |

| Binomial name | |

| Vaccinium arboreum Marshall | |

| |

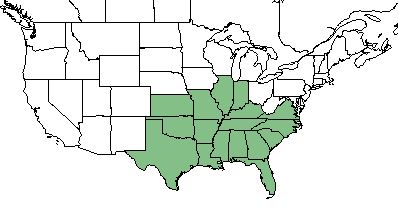

| Natural range of Vaccinium arboreum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonym: Batodendron arboreum (Marshall) Nuttall.

Varieties: V. arboreum var. arboreum; V. arboreum var. glaucescens (Greene) Sargent.

Description

V. arboreum is a perennial shrub/tree of the Ericaceae family that is native to North America. [1]

Distribution

V. arboreum is found throughout the southeastern United States, as far west as Texas and as far north as Illinois.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

Common habitats for V. arboreum include rocky or sandy woodlands, bluffs, and cliffs. [6] Specimens have been collected from longleaf wiregrass sand ridge, broadleaf tree stand, high hammock, upland woodland, live oak hammock, mixed hardwood forest, and in beech magnolia woods.[7]

V. arboreum can grow in medium to coarse textured soils.[1] When exposed to soil disturbance by military training in West Georgia, V. arboreum responds negatively by way of absence.[8]

The species has a medium tolerance to drought and is tolerant of shade.[1]

V. arboreum responds negatively to soil disturbance from agriculture in South Carolina's longleaf communities.[9] This could also mark it as a possible indicator species for remnant woodland.[10] It does not respond to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.[11]

Vaccinium arboreum is frequent and abundant in the North Florida Longleaf Woodlands and Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[12]

Phenology

V. arboreum has been observed to flower January through May and October with peak inflorescence in April.[13]

Fruit begins to develop in summer and lasts to fall.[1]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates.[14]

Fire ecology

V. arboreum has a medium tolerance of fire.[1]

Given V. arboreum is usually maintained by fire, when the habitat is fire suppressed the species will grow to maturity and taller than in fire maintained regions.[6] [15]

Conservation and Management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 USDA Plant Database

- ↑ Behm, A. L., et al. (2004). "Flammability of native understory species in pine flatwood and hardwood hammock ecosystems and implications for the wildland-urban interface." International Journal of Wildland Fire 13: 355-365.

- ↑ Blair, R. M. (1971). "Forage production after hardwood control in a southern pine-hardwood stand." Forest Science 17(3): 279-284.

- ↑ Bowman, J. L., et al. (1999). Effects of red-cockaded woodpecker management on vegetative composition and structure and subsequent impacts on game species. Proceedings of the Fifty-third Annual Conference, Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. A. G. Wong, P. Doerr, D. Woodward, P. Mazik and R. Lequire. Greensboro, NC, Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies: 220-234.

- ↑ Lay, D. W. (1956). "Effects of prescribed burning on forage and mast production in southern pine forests." Journal of Forestry 29(9): 582-584.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: Florida (Okaloosa, Leon, De Soto, Suwannee, Gadsden, Leon, Wakulla, Taylor, Clay, Hillborough, Levy, Hernando, Citrus, Alachua, Volusia, Walton, Marion, Hamilton, Escambia, Lafayette, Sarasota, Jackson, Holmes, Baker) Georgia (Thomas, Grady) States and counties:

- ↑ Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 29 MAY 2018

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Rodgers, H. L. and L. Provencher (1999). "Analysis of Longleaf Pine Sandhill Vegetation in Northwest Florida." Castanea 64(2): 138-162.