Difference between revisions of "Lechea sessiliflora"

(→Description) |

|||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

<!--===Use by animals===--> <!--Herbivory, granivory, insect hosting, etc.--> | <!--===Use by animals===--> <!--Herbivory, granivory, insect hosting, etc.--> | ||

<!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | <!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | ||

| − | ==Conservation and | + | ==Conservation, cultivation, and restoration== |

| − | == | + | |

| + | ==Cultural use== | ||

==Photo Gallery== | ==Photo Gallery== | ||

<gallery widths=180px> | <gallery widths=180px> | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

==References and notes== | ==References and notes== | ||

Revision as of 16:56, 8 June 2021

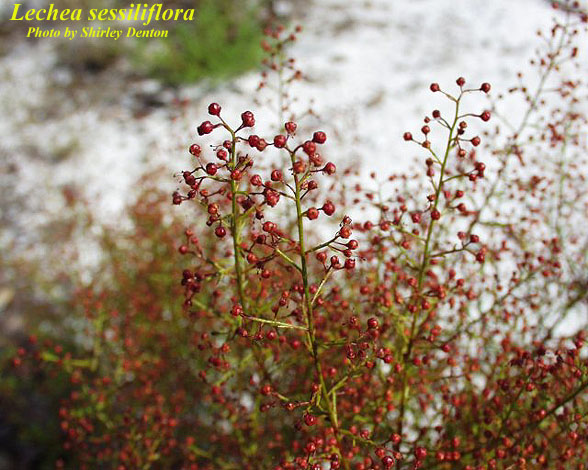

| Lechea sessiliflora | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Shirley Denton (Copyrighted, use by photographer’s permission only), Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Cistaceae |

| Genus: | Lechea |

| Species: | L. sessiliflora |

| Binomial name | |

| Lechea sessiliflora Raf. | |

| |

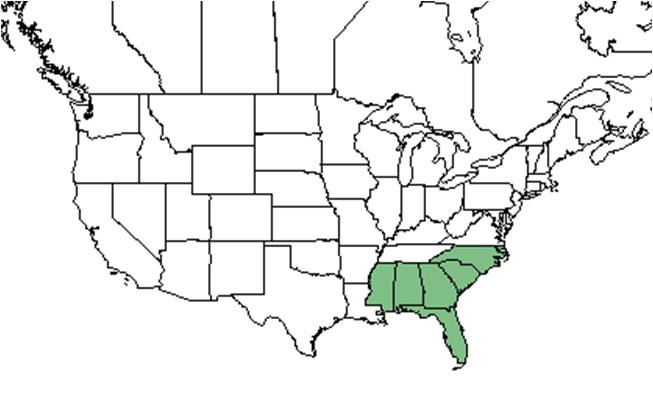

| Natural range of Lechea sessiliflora from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Pineland pinweed[1]

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Lechea patula Leggett; L. exserta Small; L. prismatica Small.[1]

Varieties: none.[1]

Lechea species can be hard to distinguish from each other due to microscopic differences, often leading to problems with correct nomenclature.[2]

Description

Lechea sessiliflora is a herbaceous perennial distinguished from other Lechea species by having a conspicuously exserted, ellipsoid capsule that is capped by a reddish-brown fimbriate stigma.[3] The species in Lechea have a distinctive calyx with the two outer sepals very different in size and shape from the three inner sepals.[2] It is often mistaken for L. deckertii because both species have prominently exserted straw-colored capsules with persistent stigmas. The easiest way to distinguish these two species is by the length of the outer slender sepals and the shape of the capsules. L. sessiliflora has ellipsoid capsules and the narrow outer sepals are almost equaling or a little longer than the broad inner sepals.[3]

L. sessiliflora does not have specialized underground storage units apart from its taproot.[4] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an non-structural carbohydrate concentration of 143.2 mg/g (ranking 45 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 46.7% (ranking 62 out of 100 species studied).[4]

Distribution

This plant ranges from southern North Carolina to southern Florida, then west to southern Mississippi.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

Habitats include longleaf pine-wiregrass communities, pine-scrub oak barrens, coastal scrubs, and dry pine flatwoods. It is found in disturbed areas such as cutover pine communities, sandy roadsides, former live oak plantations, and along railroad tracks. L. sessiliflora responds negatively to soil disturbance by agriculture in Southwest Georgia.[5]

Associated species include Dalea, Eupatorium, Liatris, Pityopsis, Symphotrichum, and Schizachyrium. Soil types include loamy sand and sand.[6]

Lechea sessiliflora is an indicator species for the Peninsula Xeric Sandhills community type and is frequent and abundant in the North Florida SUbxeric Sandhills community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[7]

Phenology

L. sessiliflora flowers from July through August and fruits from August through October.[1]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity.[8]

Seed bank and germination

Kirkman found the vulnerability ratio for soil disturbance to be 3/3(reference sites/recovery sites).[9]

Pollination

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Lechea sessiliflora at Archbold Biological Station:[10]

Halictidae: Lasioglossum placidensis

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Barringer, K. (2004). "New Jersey Pinweeds (Lechea, Cistaceae)." The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 131(3): 261-276.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 [[1]]Accessed January 11, 2016

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.

- ↑ Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: October 2015. Collectors: C. Anderson, M. Davis, Robert K. Godfrey, R. Komarek, H. Roth. States and Counties: Florida: Calhoun, Franklin, Gadsden, Gulf, Jackson, Leon, Suwannee, Taylor, Wakulla, Walton. Georgia: Grady. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. K., K. L. Coffey, et al. (2004). "Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna." Journal of Ecology 92(3): 409-421.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.