Difference between revisions of "Hymenachne hemitomon"

Emmazeitler (talk | contribs) (→Taxonomic Notes) |

|||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

<!--==Diseases and parasites==--> | <!--==Diseases and parasites==--> | ||

| − | ==Conservation and | + | ==Conservation, cultivation, and restoration== |

It is considered a species of special concern by the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, Natural Heritage Program.<ref name= "USDA"/> It is also considered vulnerable in Maryland and imperiled in North Carolina, Virginia, Delaware, and New Jersey.<ref>[[http://explorer.natureserve.org]] NatureServe Explorer. Accessed: May 22, 2019</ref> For management, fertilization can help establish new plantings or when it is used as ofrage since it responds favorably to fertilization. To maintain healthy stands for grazing, no more than half of its biomass should be removed by either cutting or grazing. On the other hand, ''H. hemitomon'' is also considered to have growth characteristics that can make it become weedy or invasive in some habitats or regions since it has growth characteristics that can help it grow into monotypic stands. This species can be controlled through mowing, with fire, or with hydroperiod management, and herbicides can also be used to create wetland openings.<ref name= "fact"/> | It is considered a species of special concern by the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, Natural Heritage Program.<ref name= "USDA"/> It is also considered vulnerable in Maryland and imperiled in North Carolina, Virginia, Delaware, and New Jersey.<ref>[[http://explorer.natureserve.org]] NatureServe Explorer. Accessed: May 22, 2019</ref> For management, fertilization can help establish new plantings or when it is used as ofrage since it responds favorably to fertilization. To maintain healthy stands for grazing, no more than half of its biomass should be removed by either cutting or grazing. On the other hand, ''H. hemitomon'' is also considered to have growth characteristics that can make it become weedy or invasive in some habitats or regions since it has growth characteristics that can help it grow into monotypic stands. This species can be controlled through mowing, with fire, or with hydroperiod management, and herbicides can also be used to create wetland openings.<ref name= "fact"/> | ||

| − | |||

Cultivars of this species include 'Halifax', which was released from the USDA NRCS Jamie L. Whitten Plant Materials Center in 1974 located in Coffeeville, Mississippi, and Citrus Germplasm which was released by the USDA NRCS Brooksville Plant Materials Center in 1998 located in Brooksville, Florida. For restoration, ''H. hemitomon'' can be used for shoreline stabilization in locations with fresh water. This is because it has a rapid growth rate, and grows into dense stands that can extend from shallow water up along the bank as far as moisture will permit it. As well, it is capable of lessening wave energies and trapping sediment that is suspended; its roots and rhizomes form a network that anchors the soil and traps these sediments in place.<ref name= "fact"/> | Cultivars of this species include 'Halifax', which was released from the USDA NRCS Jamie L. Whitten Plant Materials Center in 1974 located in Coffeeville, Mississippi, and Citrus Germplasm which was released by the USDA NRCS Brooksville Plant Materials Center in 1998 located in Brooksville, Florida. For restoration, ''H. hemitomon'' can be used for shoreline stabilization in locations with fresh water. This is because it has a rapid growth rate, and grows into dense stands that can extend from shallow water up along the bank as far as moisture will permit it. As well, it is capable of lessening wave energies and trapping sediment that is suspended; its roots and rhizomes form a network that anchors the soil and traps these sediments in place.<ref name= "fact"/> | ||

| + | ==Cultural use== | ||

==Photo Gallery== | ==Photo Gallery== | ||

<gallery widths=180px> | <gallery widths=180px> | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

==References and notes== | ==References and notes== | ||

Revision as of 16:39, 8 June 2021

| Hymenachne hemitomon | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida - Moncots |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Genus: | Hymenachne |

| Species: | H. hemitomon |

| Binomial name | |

| Hymenachne hemitomon J.A. Schultes | |

| |

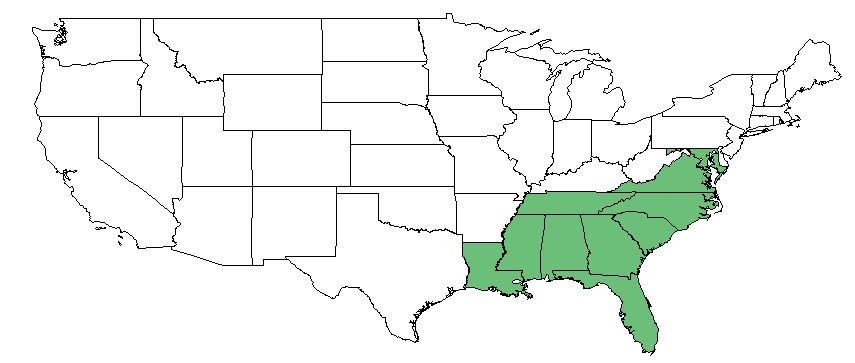

| Natural range of Hymenachne hemitomon from Weakley [1] | |

Common name(s): Maidencane

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: Panicum hemitomon J.A. Schultes.[2]

Varieties: none.[2]

Description

This species is a perennial graminoid in the Poaceae family.[3] It is a rhizomatous grass that reaches heights between 2 to 5 feet with alternate leaves and overlapping sheaths grasping the stem. Plant is glabrous containing a membranous ligule, and seed heads look very delicate. Often, reproductive stems will be much outnumbered by vegetative stems.[4]

Distribution

H. hemitomon can be found from Texas to southern New Jersey, but it is most common in Florida.[3] More specifically, it is distributed from the southeastern coastal plain from southern New Jersey south to Florida, west to Texas, and also in Tennessee, and ranges farther south to South America.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

Generally, Hymenachne hemitomon can be found in river, lake and pond shores, marshes, ditches, swamp borders, and most often in shallow water. It also commonly forms dense colonies located in shallow waters and low margins of limesink ponds.[1] This species is frequently found at swamp margins and marshy drainage canals in wet soil or shallow, standing water [5]. It can be found in coastal as well as freshwater marshes, canals, and cypress-gum ponds additionally.[6] Sandhills and wetlands are possible habitats for Hymenachne hemitomon.[7] Within the Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plain, H. hemitomon is considered an obligate wetland species that can only be found in wetland habitats.[3] It is tolerant of a large range of soil textures and anaerobic conditions, but is not tolerant of salt, and mostly prefers an almost neutral pH.[4] It is considered an indicator species of wet depression prairies in Florida, and is usually the dominant species in the habitat.[8]

Associated species include Leersia sp., Eleocharis sp., Polygonum sp., Nelumbo sp., Carex sp., Juncus sp., Rhynchospora sp., Saururus sp., Centella sp., Canna sp., Stilligia aquatica, Nyphaea sp., and others.[5]

Phenology

H. hemitomon has been observed to flower from the beginning of may to September with peak inflorescence in May and June [5][9], but flowering is most common from June to July.[1] It has been found to fruit most abundantly in wet years that follow drought periods.[6]

Seed dispersal

In time periods with standing water, seeds of H. hemitomon can move to and from differing zones in wetland habitats.[10]

Seed bank and germination

Since this species is not a dependable seed producer, it typically established itself by vegetative propagules instead.[4] One study on a constructed reservoir in South Carolina found H. hemitomon to germinate from seeds located in the seed bank of coves, points, and straights, and seeds were evenly distributed in all depths in the seed bank.[11]

Fire ecology

This species is fire tolerant if roots and rhizomes are moist.[4] But if burned during a dry season, it will be destroyed.[12] When H. hemitomon is burned in the late fall, it provides nesting and a source of food for mammals, birds, reptiles, vertebrates, and amphibians. If burned during stable conditions, it will have faster and healthier resprouts that produce new shoots 3 to 4 days after a fire disturbance, and are considerably denser than originally 6 months after a fire disturbance. Additionally, fire disturbance increases phenological activity and increases the number of inflorescences produced. However, inundation post-fire and late season burn regiments have been found to not create these desirable effects.[6]

Use by animals

This species is very palatable to livestock, and is an important forage grass.[4] It has been proven to be high in crude protein, and digestability hits a peak of 50% and protein peaks at 10 to 11% when grazed. However, when the plant dies back it is less desirable as grazing food.[6] With other wildlife, it is considered to have a fair forage value. It provides cover and habitat for many mammals, amphibians, reptiles, fish, and birds. It also is frequently used by the Florida Panther and white-tailed deer.[4]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

It is considered a species of special concern by the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, Natural Heritage Program.[3] It is also considered vulnerable in Maryland and imperiled in North Carolina, Virginia, Delaware, and New Jersey.[13] For management, fertilization can help establish new plantings or when it is used as ofrage since it responds favorably to fertilization. To maintain healthy stands for grazing, no more than half of its biomass should be removed by either cutting or grazing. On the other hand, H. hemitomon is also considered to have growth characteristics that can make it become weedy or invasive in some habitats or regions since it has growth characteristics that can help it grow into monotypic stands. This species can be controlled through mowing, with fire, or with hydroperiod management, and herbicides can also be used to create wetland openings.[4]

Cultivars of this species include 'Halifax', which was released from the USDA NRCS Jamie L. Whitten Plant Materials Center in 1974 located in Coffeeville, Mississippi, and Citrus Germplasm which was released by the USDA NRCS Brooksville Plant Materials Center in 1998 located in Brooksville, Florida. For restoration, H. hemitomon can be used for shoreline stabilization in locations with fresh water. This is because it has a rapid growth rate, and grows into dense stands that can extend from shallow water up along the bank as far as moisture will permit it. As well, it is capable of lessening wave energies and trapping sediment that is suspended; its roots and rhizomes form a network that anchors the soil and traps these sediments in place.[4]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 USDA Plants Database: https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=PAHE2

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Shadow, R. A. (2012). Plant Fact Sheet: Maidencane Panicum hemitomon. N.R.C.S. United States Department of Agriculture. East Texas Plant Materials Center, Nacogdoches, Texas.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: May 2018. Collectors: George R. Cooley, R. J. Eaton, Carroll E. Wood, Jr., C. Earle Smith, Jr., Robert K. Godfrey, Loran C. Anderson, M. Darst, R. Mattson, L. Peed, Grady W. Reinert, K. Craddock Burks, P.L. Redfearn, Jr., R. Kral, Jackson, Kurz, R. J. Vogl, R. F. Doren, William Lindsey, and Julie Neel. States and Counties: Florida: Citrus, Columbia, Gadsden, Gilchrist, Gulf, Hamilton, Hernando, Leon, Levy, Madison, Marion, Nassau, Okaloosa, Osceola, St. Johns, Union, Volusia, Wakulla, and Washington. Georgia: Thomas.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Newman, S. D. and M. Materne. (2006). Plant Guide: Maidencane Panicum hemitomon. N.R.C.S. United States Department of Agriculture. Baton Rouge, LA.

- ↑ Comment by Edwin Bridges, on post by Adam Julius Arendell, July 18, 2016, posted to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Facebook Group July 2016.

- ↑ Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 22 MAY 2019

- ↑ Poiani, K. A. and P. M. Dixon (1995). "Seed banks of Carolina bays: potential contributions from surrounding landscape vegetation " American Midland Naturalist 134: 140-154

- ↑ Collins, B. and G. Wein (1995). "Seed bank and vegetation of a constructed reservoir." Wetlands 15(4): 374-385.

- ↑ Garren, K. H. (1943). "Effects of fire on vegetation of the southeastern United States." Botanical Review 9(9): 617-654.

- ↑ [[1]] NatureServe Explorer. Accessed: May 22, 2019