Difference between revisions of "Desmodium laevigatum"

Emmazeitler (talk | contribs) (→Taxonomic notes) |

|||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

<!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | <!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | ||

| − | ==Conservation and | + | ==Conservation, cultivation, and restoration== |

''D. laevigatum'' is listed as endangered by the New York Department of Environmental Conservation, Division of Land and Forests.<ref name= "USDA">USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 26 April 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.</ref> | ''D. laevigatum'' is listed as endangered by the New York Department of Environmental Conservation, Division of Land and Forests.<ref name= "USDA">USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 26 April 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.</ref> | ||

| − | + | ==Cultural use== | |

| − | == | ||

==Photo Gallery== | ==Photo Gallery== | ||

<gallery widths=180px> | <gallery widths=180px> | ||

Revision as of 14:08, 8 June 2021

| Desmodium laevigatum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae ⁄ Leguminosae |

| Genus: | Desmodium |

| Species: | D. laevigatum |

| Binomial name | |

| Desmodium laevigatum (Nutt.) DC. | |

| |

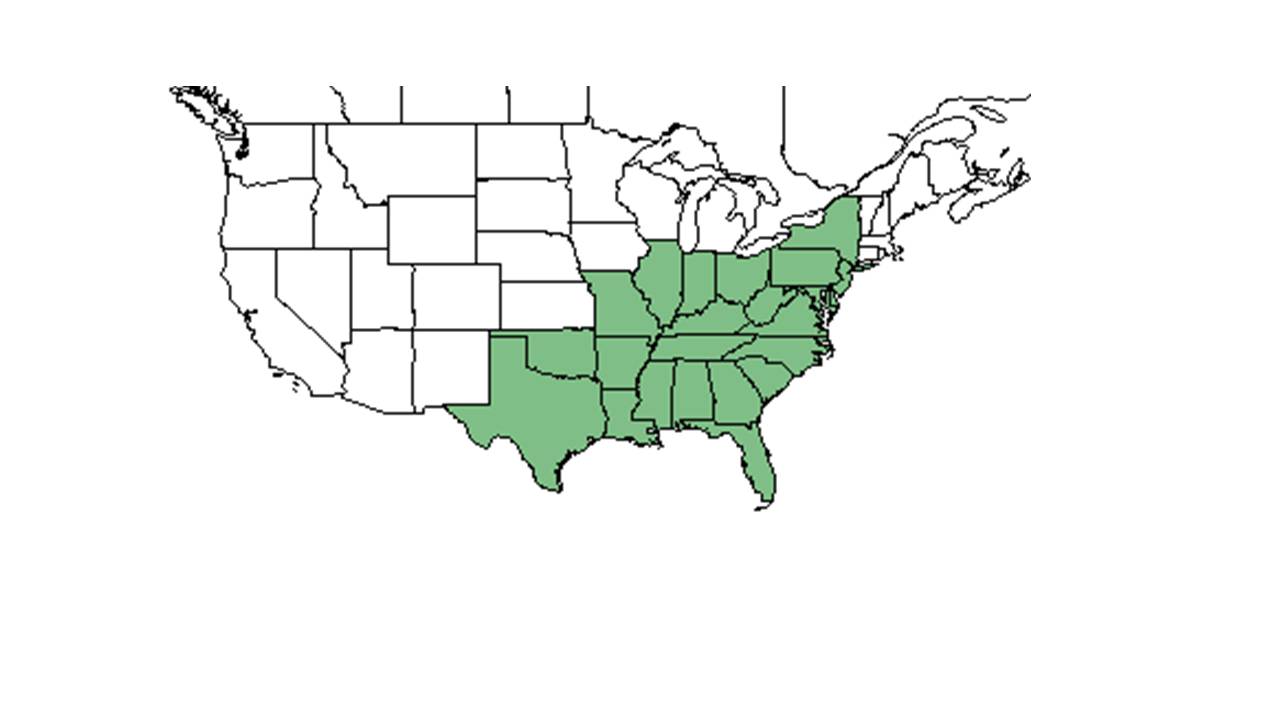

| Natural range of Desmodium laevigatum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Smooth Tick-trefoil

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonym: Meibomia laevigata (Nuttall) Kuntze.[1]

Varieties: none.[1]

Description

Generally for the Desmodium genus, they are "annual or perennial herbs, shrubs or small trees. Leaves 1-5 foliolate, pinnately 3-foliolate in ours or rarely the uppermost or lowermost 1-foliolate; leaflets entire, usually stipellate; stipules caduceus to persistent, ovate to subulate, foliaceous to setaceous, often striate. Inflorescence terminal and from the upper axils, paniculate or occasionally racemose; pedicel of each papilionaceous flower subtended by a secondary bract or bractlet, the cluster of 1-few flowers subtended by a primary bract. Calyx slightly to conspicuously 2-lipped, the upper lip scarcely bifid, the lower lip 3-dentate; petals pink, roseate, purple, bluish or white; stamens monadelphous or more commonly diadelphous and then 9 and 1. Legume a stipitate loment, the segments 2-many or rarely solitary, usually flattened and densely uncinated-pubescent, separating into 1-seeded, indehiscent segments." [2]

Specifically, for D. laevigatum species, they are "erect perennial; stems 0.5-1.2 m tall, glabrous to sparsely and inconspicuously uncinulate-puberulent. Terminal leaflets ovate to elliptic-ovate or elliptic-oblong, (3) 4-7 (9) cm long, glabrous to very sparsely puberulent above, glabrous to puberulent or sparsely short-pilose, often glaucous beneath with the trichomes largely restricted to the principal veins; stipules caduceus, lance-attenuate, 5-8 mm long; stipels persistent. Inflorescence usually paniculate, moderately to densely uncinulate-puberulent; pedicels mostly 7-19 mm long. Calyx densely puberulent; petals pink or roseate to purple, 8-10 mm long; stamens diadelphous. Loment of 2-5 subrhombic segments, each about 5-8 mm long, 3.5-5 mm broad, with a straight or slightly convex upper suture and an abruptly angled lower suture, with densely uncinulate sutures; stipe ca. 4.5-6.5 mm longer, much longer than the calyx tube but often equaling or even exceeding the calyx lobes, shorter than stamina remnants." [2]

Distribution

D. laevigatum is native to the United States from south New York west to Indiana and Missouri, south to north Florida and the panhandle, and west to Texas.[3]

Ecology

Habitat

This species is commonly found in fields, woodland borders, pine and dry oak forests, and disturbed areas in its native distribution.[3] It has been observed in areas that frequently burn such as open woods bordering a bay, hardwood hammocks, upland pine, in open mixed pine-hardwood forest, well drained upland, savannas, turkey oak sand ridges. Requires low-high light levels. Is associated with loamy sand, sandy clay loam, limestone, and sand soil types.[4] Where it is found, it is infrequent compared to other Desmodium species that can be found in the same habitat.[5] D. laevigatum has been found to respond positively to disturbance, where a study found flowering to increase in response to tornado damage and in turn an increase in light.[6] D. laevigatum responds positively to clearcutting and chopping in South Carolina.[7]

Associated species include Desmodium ciliare, D. lineatum, D. glabellum.[4]

Phenology

D. laevigatum commonly flowers between June and September and fruits between August and October.[3] It has been observed flowering from September to November with peak inflorescence in September; it is also been observed fruiting during the same time period.[8][4]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by translocation on animal fur or feathers. [9]

Fire ecology

It has been observed in areas that are frequently burned[4], but has also been found in areas that are fire excluded which means it is not fully fire dependent.[10] For fire seasonality, one study found greatest abundance after a summer burn rather than a spring burn.[11]

Use by animals

It consists of approximately 10-25% of the diet for large mammals and terrestrial birds.[12] D. laevigatum has been recorded as a food source for white-tailed deer as well as northern bobwhite quail.[13][14]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

D. laevigatum is listed as endangered by the New York Department of Environmental Conservation, Division of Land and Forests.[15]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 604-11. Print.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, R.K. Godfrey, Angus Gholson, A. F. Clewell, V. Sullivan, J. Wooten, R. Kral, R. Komarek, T. MacClendon, - Boothes, Travis MacClendon, Karen MacClendon, Geo. Wilder, Harry E. Ahles, C. R. Bell, H. R. Reed, Delzie Demaree, William B. Fox, and S. G. Boyce. States and Counties: Alabama: Etowah, Franklin, and Lee. Arkansas: Drew. Florida: Bay, Calhoun, Franklin, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Liberty, Okaloosa,and Wakulla. Georgia: Baker, Decatur, Grady,and Thomas. Mississippi: Pearl River. North Carolina: Sampson. South Carolina: Beaufort. Virginia: Montgomery.

- ↑ Hainds, M. J., et al. (1999). "Distribution of native legumes (Leguminoseae) in frequently burned longleaf pine (Pinaceae)-wiregrass (Poaceae) ecosystems." American Journal of Botany 86: 1606-1614.

- ↑ Brewer, S. J., et al. (2012). "Do natural disturbances or the forestry practices that follow them convert forests to early-successional communities?" Ecological Applications 22: 442-458.

- ↑ Cushwa, C.T. and M.B. Jones. (1969). Wildlife Food Plants on Chopped Areas in Piedmont South Carolina. Note SE-119. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station. 4 pp.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 26 APR 2019

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Clewell, A. F. (2014). "Forest development 44 years after fire exclusion in formerly annually burned oldfield pine woodland, Florida." Castanea 79: 147-167.

- ↑ Cushwa, C. T., et al. (1970). Response of legumes to prescribed burns in loblolly pine stands of the South Carolina Piedmont. Asheville, NC, USDA Forest Service, Research Note SE-140: 6.

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Atwood, E. L. (1941). "White-tailed deer foods of the United States." The Journal of Wildlife Management 5(3): 314-332.

- ↑ Hamrick, R., et al. (2007). Ecology & management of northern bobwhite. Publication 2179. Mississippi State, MS, Mississippi State University [Extension Service of Mississippi State University, cooperating with U.S. Department of Agriculture].

- ↑ USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 26 April 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.