Difference between revisions of "Tephrosia virginiana"

Krobertson (talk | contribs) (→Fire ecology) |

Krobertson (talk | contribs) (→Fire ecology) |

||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

===Fire ecology=== | ===Fire ecology=== | ||

| − | ''T. virginiana'' re-sprouts rapidly following fire and flowers within three months of burning.<ref name="Robertson"/> Conversely, flowering quite limited during years without fire.<ref>Hiers, J. K., R. Wyatt and R. J. Mitchell 2000. The effects of fire regime on legume reproduction in longeaf pine savannas: is season selective? Oecologia 125:521-530.</ref> Burning has also been shown to decrease the percentage of seeds that germinate. However, this is only true when course fuels (e.g. pine cones), and not fine fuels (e.g. pine needles), are present. Models suggest these course fuels produce mortality close to the fuel but fails to scarify seeds further away; this leaves an area between the two where scarification and germination can occur.<ref name="Wiggers et al 2013"/> | + | ''T. virginiana'' re-sprouts rapidly following fire and flowers within three months of burning.<ref name="Robertson"/> Conversely, flowering is quite limited during years without fire.<ref>Hiers, J. K., R. Wyatt and R. J. Mitchell 2000. The effects of fire regime on legume reproduction in longeaf pine savannas: is season selective? Oecologia 125:521-530.</ref> Burning has also been shown to decrease the percentage of seeds that germinate. However, this is only true when course fuels (e.g. pine cones), and not fine fuels (e.g. pine needles), are present. Models suggest these course fuels produce mortality close to the fuel but fails to scarify seeds further away; this leaves an area between the two where scarification and germination can occur.<ref name="Wiggers et al 2013"/> |

<!--===Pollination===--> | <!--===Pollination===--> | ||

Revision as of 16:37, 21 October 2019

| Tephrosia virginiana | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Genus: | Tephrosia |

| Species: | T. virginiana |

| Binomial name | |

| Tephrosia virginiana (L.) Pers. | |

| |

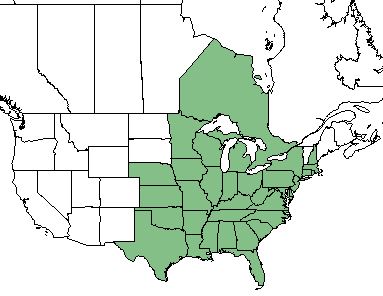

| Natural range of Tephrosia virginiana from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common Name(s): Virginia goat's-rue;[1] Virginia tephrosia;[2][3] goat's rue; devil's shoestring[3]

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: T. virginiana var. glabra Nuttall; T. virginiana var. virginiana; Cracca virginiana Linnaeus

Description

Tephrosia virginiana is covered with soft white hairs, which makes it silvery green in appearance. It grows to 1-3 ft (0.30-0.91 m) and has long stringy roots, from which it gets the name devil's shoestring. Leaves are pinnately compound with 8-15 pairs of leaflets. Flowers are bi-colored with pink and pale yellow and typically cluster at the tip of the stem. In southern portions of its range, flowers can initially be white but will change over time.[3] T. virgininana is hard seeded, thus requiring scarification.[4]

Distribution

This species is found from Texas, eastward to Florida, northward to New Hampshire and New York, and inland to Minnesota and Nebraska.[1][2] It is also reported to occur in the Ontario province of Canada.[2]

Ecology

Habitat

T. virginiana is found in sandhills, other pinelands, xeric or rocky woodlands and forests, outcrops, shale barrens, other barrens, and dry roadbanks.[1] In South Carolina forests, it is found in 72% of sites while only 0 and 8% in pastures and cultivated fields.[5] It is considered a characteristic legume species of shortleaf pine-oak-hickory woodlands[6] and longleaf pine/wiregrass communities.[7] It is considered indicative of non-agricultural history on frequently burned longleaf pine habitats.[8]

T. virginiana displays a negative response to agriculture-based soil disturbance in historically longleaf communities from South Carolina.[9] This could also mark it as a possible indicator species for remnant woodland.[10][11] T. virginiana responds negatively to soil disturbance by agriculture in Southwest Georgia.[12][13]

This species is one of several species positively associated with Linum intercursum and Scleria pauciflora. [14]

Phenology

T. virginiana has been observed to flower April through June.[1][15] Fruiting occurs from July through October.[1] Germination occurs from March through June when seasonal temperatures are increasing.[16] Flowering is stimulated by fire and occurs within three months of burning.[17]

Seed bank and germination

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity. [18] In Georgia, seeds buried in a seed bag for 1 and 2 years yielded 61 and 50% rates of germination, respectively.[16]

Fire ecology

T. virginiana re-sprouts rapidly following fire and flowers within three months of burning.[17] Conversely, flowering is quite limited during years without fire.[19] Burning has also been shown to decrease the percentage of seeds that germinate. However, this is only true when course fuels (e.g. pine cones), and not fine fuels (e.g. pine needles), are present. Models suggest these course fuels produce mortality close to the fuel but fails to scarify seeds further away; this leaves an area between the two where scarification and germination can occur.[4]

Use by animals

T. virginiana comprises 2-5% of the diets of some large mammals and terrestrial birds.[20] Common grasshoppers, including Melanopus angustipennis and grasshoppers in the subfamilies Melanoplinae and Cyrtacanthacridinae, are mixed feeders and found to feed on this plant. However, herbivory did not affect overall biomass or mortality of the plant.[8] In the past, it was used as a goat feed to increase milk production. However, this use stopped after tephrosin, an insecticide and fish poison, was found in it.[3]

Conservation and Management

Cultivation and restoration

Seeds can be collected from August to September. To propagate from seeds, scarification, inoculation, and 10 days of moist stratification should occur.[3]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley A. S.(2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 12 January 2018). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Plant database: Tephrosia virginiana. (12 January 2018) Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. URL: https://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=TEVI

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Wiggers MS, Kirkman LK, Boyd RS, Hiers JK (2013) Fine-scale variation in surface fire environment and legume germination in the longleaf pine ecosystem. Forest Ecology and Management 310:54-63.

- ↑ Brudvig LA, Damschen EI (2011) Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34:257-266.

- ↑ Clewell AF (2013) Prior prevalence of shortleaf pine-oak-hickory woodlands in the Tallahassee red hills. Castanea 78(4):266-276.

- ↑ Andreu MG, Hedman CW, Friedman MH, Andreu AG (2009) Can managers bank on seed banks when restoring Pinus taeda L. plantations in southwest Georgia? Restoration Ecology 17(5):586-596.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Hahn, P. C. and J. L. Orrock (2015). "Land-use legacies and present fire regimes interact to mediate herbivory by altering the neighboring plant community." Oikos 124: 497-506.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.

- ↑ Hedman, C.W., S.L. Grace, and S.E. King. (2000). Vegetation composition and structure of southern coastal plain pine forests: an ecological comparison. Forest Ecology and Management 134:233-247.

- ↑ Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.

- ↑ Clarke GL, Patterson WA III (2007) The distribution of disturbance-dependent rare plants in a coastal Massachusetts sandplain: Implications for conservation and management. Biological Conservation 136:4-16.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 12 JAN 2018

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Coffey KL, Kirkman LK (2006) Seed germination strategies of species with restoration potential in a fire-maintained pine savanna. Natural Areas Journal 26(3):289-299.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Robertson, K. 2015. personal observation at Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, near Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Hiers, J. K., R. Wyatt and R. J. Mitchell 2000. The effects of fire regime on legume reproduction in longeaf pine savannas: is season selective? Oecologia 125:521-530.

- ↑ Miller JH, Miller KV (1999) Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.