Difference between revisions of "Solidago altissima"

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ||

| − | ''S. altissima'' is found in roadsides,<ref name="Weakley 2015"/><ref name="Ladybird"/> fields, disturbed areas,<ref name="Weakley 2015"/> thickets, prairies, open woods,<ref name="Ladybird"/> stream banks, and marshes.<ref name="Bostick 1971">Bostick PE (1971) Vascular plants of Panola Mountain, Georgia. Castanea 36(3):194-209.</ref> It prefers moist to dry soils composed of clay, clay loam, medium loam, sandy loam, sandy and caliche.<ref name="Ladybird"/> In a Wisconsin Prairie, the frequency in 1951 was 32 and in 1961 was 48.<ref name="Anderson 1973">Anderson RC (1973) The use of fire as a management tool on the Curtis Prairie. Proceedings Annual [12th] Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: a quest for ecological understanding. Lubbock, TX pg 23-35.</ref> | + | ''S. altissima'' is found in roadsides,<ref name="Weakley 2015"/><ref name="Ladybird"/> fields, disturbed areas,<ref name="Weakley 2015"/> thickets, prairies, open woods,<ref name="Ladybird"/> stream banks, and marshes.<ref name="Bostick 1971">Bostick PE (1971) Vascular plants of Panola Mountain, Georgia. Castanea 36(3):194-209.</ref> It prefers moist to dry soils composed of clay, clay loam, medium loam, sandy loam, sandy and caliche.<ref name="Ladybird"/> In a Wisconsin Prairie, the frequency in 1951 was 32 and in 1961 was 48.<ref name="Anderson 1973">Anderson RC (1973) The use of fire as a management tool on the Curtis Prairie. Proceedings Annual [12th] Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: a quest for ecological understanding. Lubbock, TX pg 23-35.</ref> Also on Wisconsin prairies, aboveground biomass from 1987-1993 averaged 838.4 ± 92.8 g m<sup>-2</sup>.<ref name="Howe 1995"/> |

===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ||

Revision as of 14:04, 19 January 2018

| Solidago altissima | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae |

| Genus: | Solidago |

| Species: | S. altissima |

| Binomial name | |

| Solidago altissima L. | |

| |

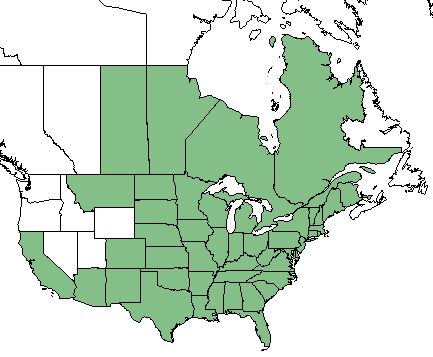

| Natural range of Solidago altissima from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common Name(s): tall goldenrod; Great Plains tall goldenrod; southern tall goldenrod;[1] Canada goldenrod;[2] Canadian goldenrod; late goldenrod[3]

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Varieties: S. altissima var. altissima; S. altissima var. pluricephala;[1][2] S. altissima var. gilvocanescens;[1] S. altissima var. procera[2]

Synonym(s): S. canadensis var. scabra; S. hirsutissima;[1][2] S. pruinosa; S. canadensis var. gilvocanescens;[1] S. lunellii[2]

Description

Solidago altissima is a dioecious perennial forb/herb.[2] This plant is rough, erect, and produces small yellow flowers that are arranged along upper side of branches, producing a plume. It reaches heights of 3-6 ft (0.91-1.83 m)[3] and forms large compact below-ground rhizome systems.[4]

Distribution

This species is found in all of the lower 48 United States, excluding Washington, Oregon, Nevada, Utah, Idaho, and Wyoming. It also occurs in the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and New Brunswick.[2] S. altissima is also an exotic invasive in Europe (as cited in [4]).

Ecology

Habitat

S. altissima is found in roadsides,[1][3] fields, disturbed areas,[1] thickets, prairies, open woods,[3] stream banks, and marshes.[5] It prefers moist to dry soils composed of clay, clay loam, medium loam, sandy loam, sandy and caliche.[3] In a Wisconsin Prairie, the frequency in 1951 was 32 and in 1961 was 48.[6] Also on Wisconsin prairies, aboveground biomass from 1987-1993 averaged 838.4 ± 92.8 g m-2.[7]

Phenology

Flowering occurs from August through November.[1][8]

Fire ecology

On a Wisconsin tallgrass prairie, two burn cycles of a 3 year interval showed increases in cover during spring and summer burns. However, an increase in cover also occurred on unburned sites, suggesting the burn cycle did not negatively affect S. altissima cover but may not be responsible for the increase.[7]

Pollination

S. altissima attracts birds, butterflies, and a large number of native bees.[3]

Use by animals

S. altissima responds to insect herbivory by spending energy to maintain itself, rather than producing seeds.[9] There are at least 103 species of insect herbivores of S. altissima, 42 (from 17 families) are specialists on Solidagospp.[10]

Conservation and Management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Weakley AS (2015) Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 USDA NRCS (2016) The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 118 January 2018). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Plant database: Solidago altissima. (18 January 2018) Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. URL: https://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=SOAL6

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Meyer AH, Schmid B (1999) Experimental demography of rhizome populations of establishing clones of Solidago altissima. Journal of Ecology 87(1):42-54. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Meyer & Schmid 1999" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Bostick PE (1971) Vascular plants of Panola Mountain, Georgia. Castanea 36(3):194-209.

- ↑ Anderson RC (1973) The use of fire as a management tool on the Curtis Prairie. Proceedings Annual [12th] Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: a quest for ecological understanding. Lubbock, TX pg 23-35.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Howe HF (1995) Succession and fire season in experimental prairie plantings. Ecology 76(6):1917-1925.

- ↑ Nelson G (18 January 2018) PanFlora. Retrieved from gilnelson.com/PanFlora/

- ↑ Root RB (1996) Herbivore pressure on goldenrods (Solidago altissima): Its variation and cumulative effects. Ecology 77(4):1074-1087.

- ↑ Root RB & Cappuccino N (1992) Patterns in population change and the organization of the insect community associated with goldenrod. Ecological Monographs 62(3):393-420.