Difference between revisions of "Tillandsia usneoides"

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

Although not comprising a significant portion of their diet, ''T. usneoides'' is commonly found in the rumens of fallow deer throughout the year.<ref name="Morse et al 2009">Morse BW, McElroy ML, Miller KV (2009) Seasonal diets of an introduced population of fallow deer on little St. Simons Island, Georgia. Southeastern Naturalist 8(4):571-586.</ref> Spanish moss can also be used as a food for cattle, especially in the winter when other food may be scarce.<ref name="Rafinesque 1830">Rafinesque CS (1828) Medical Flora; or Manual of the Medical Botany of the United States of North America. Atkinson SC, Philadelphia.</ref> Some birds will use strands of ''T. usneoides'' to build their nests.<ref name="Billings 1904"/> Thrips are also found in the moss and will lay an egg after punturing the base of the style.<ref name="Billings 1904"/><br> | Although not comprising a significant portion of their diet, ''T. usneoides'' is commonly found in the rumens of fallow deer throughout the year.<ref name="Morse et al 2009">Morse BW, McElroy ML, Miller KV (2009) Seasonal diets of an introduced population of fallow deer on little St. Simons Island, Georgia. Southeastern Naturalist 8(4):571-586.</ref> Spanish moss can also be used as a food for cattle, especially in the winter when other food may be scarce.<ref name="Rafinesque 1830">Rafinesque CS (1828) Medical Flora; or Manual of the Medical Botany of the United States of North America. Atkinson SC, Philadelphia.</ref> Some birds will use strands of ''T. usneoides'' to build their nests.<ref name="Billings 1904"/> Thrips are also found in the moss and will lay an egg after punturing the base of the style.<ref name="Billings 1904"/><br> | ||

| − | Humans also use Spanish moss for various things. When allowed to rot in water, a horse hair like black fiber remains that can be used to stuff mattresses and cushions or make ropes. During the 1800's, it was used as a stomachic, purgative, and diuretic<ref name="Rafinesque 1830"/><ref name="Porcher 1869">Porcher FP (1869) Resources of the Southern Fields and Forests, Medical, Economical and Agricultural. Walker, Evans and Cogswell Printers.</ref> and native Americans would drink it as a tea to relieve chills and fever.<ref name="Speck 1941">Speck FG (1941) A list of plant curatives obtained from the Houma Indians of Louisiana. Primitive Man 14(4):49-73.</ref> It is also useful for making rope or cords.<ref name="Speck 1941"/> More recently, ''T. usneoides'' is used for the biomonitoring of atmospheric metallic pollution.<ref name="Figueiredo 2007">Figueiredo AMG, Nogueira CA, Saiki M, Milian FM, Domingos M (2007) Assessment of atmospheric metallic pollution in the metropolitan region of Sao Paulo, Brazil, employing ''Tillandsia usneoides'' L. as biomonitor. Environmental Pollution 145:279-292.</ref> | + | Humans also use Spanish moss for various things. When allowed to rot in water, a horse hair like black fiber remains that can be used to stuff mattresses and cushions or make ropes. During the 1800's, it was used as a stomachic, purgative, and diuretic<ref name="Rafinesque 1830"/><ref name="Porcher 1869">Porcher FP (1869) Resources of the Southern Fields and Forests, Medical, Economical and Agricultural. Walker, Evans and Cogswell Printers.</ref> and native Americans would drink it as a tea to relieve chills and fever.<ref name="Speck 1941">Speck FG (1941) A list of plant curatives obtained from the Houma Indians of Louisiana. Primitive Man 14(4):49-73.</ref> It is also useful for making rope or cords.<ref name="Speck 1941"/> More recently, ''T. usneoides'' is used for the biomonitoring of atmospheric metallic pollution, including zinc, cobalt, barium, iron, rubidium, and many more.<ref name="Figueiredo 2007">Figueiredo AMG, Nogueira CA, Saiki M, Milian FM, Domingos M (2007) Assessment of atmospheric metallic pollution in the metropolitan region of Sao Paulo, Brazil, employing ''Tillandsia usneoides'' L. as biomonitor. Environmental Pollution 145:279-292.</ref> |

<!--==Diseases and parasites==--> | <!--==Diseases and parasites==--> | ||

Revision as of 20:06, 11 January 2018

| Tillandsia usneoides | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John Gwaltney hosted at Southeastern Flora.com | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida - Moncots |

| Order: | Bromeliales |

| Family: | Bromeliaceae |

| Genus: | Tillandsia |

| Species: | T. usneoides |

| Binomial name | |

| Tillandsia usneoides L. | |

| |

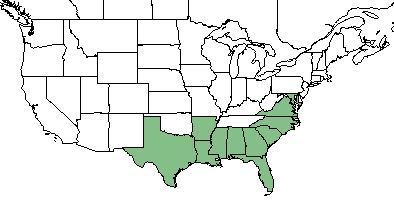

| Natural range of Tillandsia usneoides from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common Name(s): Spanish-moss,[1][2][3] long moss, black moss[3]

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonym(s): Dendropogon usneoides,[1][2] Renealmia usneoides[2]

Description

Tillandsia usneoides is an epiphyte, air plant able of photosynthesis,[4] that typically is found hanging from the branches of trees.[1] It is classified as a monoecious perennial that grows as a forb/herb or vine.[2] Leaves are whitish gray in color and its flowers are white solitary inconspicuous flowers which occur at the end of short axillary branches.[4]

Distribution

This species is found along the coastal plain in eastern Texas, eastward to Florida, and northward Maryland. It also occurs in parts of Mexico, Central and South America, the West Indies.[1][2]

Ecology

Habitat

T. usneoides requires areas with high humidity and is therefore common in swamps.[1] It can also be found in dry forests, including sandhills, where frequent fog occurs.[1] Although tolerant of shade, it seems to prefer areas where direct sunshine occurs.[3]

Phenology

Flowering occurs from March through June[1][5] and may also occur in the winter from September through December.[5] In Baton Rouge, Louisiana, seeds discharge in March.[3]

Seed dispersal

The spread of T. usneoides is not consider to be a product of its seeds, as seeds are have low germination rates and are often considered relatively useless.[3] Instead, the spread of its festons by wind and animals, including birds and deer, are thought to disperse the plant.[6] There is also evidence supporting the importance of hurricanes that disperse fragmented festons and produce a surge in frequency.[3]

Seed bank and germination

Germination in T. usneoides occurs very quickly; dehiscence occurring in March can produce seedlings by early April. While seedlings can be commonly seen, they tend to remain seedlings for extended periods of time. Intermediate forms of T. usneoides are rare to find adding to the mystery of its use of seeds and growth patterns.[3]

Use by animals

Although not comprising a significant portion of their diet, T. usneoides is commonly found in the rumens of fallow deer throughout the year.[7] Spanish moss can also be used as a food for cattle, especially in the winter when other food may be scarce.[8] Some birds will use strands of T. usneoides to build their nests.[3] Thrips are also found in the moss and will lay an egg after punturing the base of the style.[3]

Humans also use Spanish moss for various things. When allowed to rot in water, a horse hair like black fiber remains that can be used to stuff mattresses and cushions or make ropes. During the 1800's, it was used as a stomachic, purgative, and diuretic[8][9] and native Americans would drink it as a tea to relieve chills and fever.[10] It is also useful for making rope or cords.[10] More recently, T. usneoides is used for the biomonitoring of atmospheric metallic pollution, including zinc, cobalt, barium, iron, rubidium, and many more.[11]

Conservation and Management

Large amounts of T. usneoides settling on tree branches can be detrimental to other plants by shading or weighing down and snapping branches. To counter these effects, people will sometimes remove T. usneoides by hand or by cutting branches of the host.[3]

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Weakley A. S.(2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 11 January 2018). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 Billings FH (1904) A study of Tillandsia usneoides. Botanical Gazette 38(2):99-121.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Plant database: ‘’Tillandsia usneoides’’. (11 January 2018).Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. URL: https://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=TIUS

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Nelson G. (11 January 2018) PanFlora. Retrieved from gilnelson.com/PanFlora/

- ↑ Schimper AFW (1884) Ueber Bau und Lebensweise der Epiphyten Westindiens. Verlag von Theodor Fischer, Cassel, Germany.

- ↑ Morse BW, McElroy ML, Miller KV (2009) Seasonal diets of an introduced population of fallow deer on little St. Simons Island, Georgia. Southeastern Naturalist 8(4):571-586.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Rafinesque CS (1828) Medical Flora; or Manual of the Medical Botany of the United States of North America. Atkinson SC, Philadelphia.

- ↑ Porcher FP (1869) Resources of the Southern Fields and Forests, Medical, Economical and Agricultural. Walker, Evans and Cogswell Printers.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Speck FG (1941) A list of plant curatives obtained from the Houma Indians of Louisiana. Primitive Man 14(4):49-73.

- ↑ Figueiredo AMG, Nogueira CA, Saiki M, Milian FM, Domingos M (2007) Assessment of atmospheric metallic pollution in the metropolitan region of Sao Paulo, Brazil, employing Tillandsia usneoides L. as biomonitor. Environmental Pollution 145:279-292.