Difference between revisions of "Hylodesmum nudiflorum"

Krobertson (talk | contribs) |

Krobertson (talk | contribs) (→Seed dispersal) |

||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

<!--===Seed bank and germination=== | <!--===Seed bank and germination=== | ||

===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ||

| − | It is generally not affected by dormant season (March-April) low-intensity fires since the heat generated by the fires does not penetrate to where the buds and rootstocks are. Huang and Boerner (2007) found that in their study, that burning alone or with thinning reduces nitrogen and phosphorous concentrations in the soil in the short-term and the long-term<ref name=huang/> | + | It is generally not affected by dormant season (March-April) low-intensity fires since the heat generated by the fires does not penetrate to where the buds and rootstocks are. Huang and Boerner (2007) found that in their study, that burning alone or with thinning reduces nitrogen and phosphorous concentrations in the soil in the short-term and the long-term.<ref name=huang/> However, burning and thinning increases net photosynthesis rates of ''D. nudiflorum'' in the mixed-oak forests of Zaleski State Forest, Ohio. Mean plant biomass was also about two times greater in burned and in burned and thinned plots than in control plots. It is possible that the enhancement of photosynthesis is a result of changes in the forest floor microclimate (e.g., soil temperature, soil moisture, litter depth).<ref name=huangetal/> Also, much more nodules were found on ''D. nudiflorum'' in the burned and in burned and thinned plots than the control plots, suggesting a potential for greater nitrogen-fixing capability.<ref name=huangetal/> |

<!--===Pollination===--> | <!--===Pollination===--> | ||

<!--===Use by animals===--><!--Herbivory, granivory, insect hosting, etc.--> | <!--===Use by animals===--><!--Herbivory, granivory, insect hosting, etc.--> | ||

Revision as of 18:14, 17 August 2016

| Hylodesmum nudiflorum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae ⁄ Leguminosae |

| Genus: | Hylodesmum |

| Species: | H. nudiflorum |

| Binomial name | |

| Hylodesmum nudiflorum (L.) DC. | |

| |

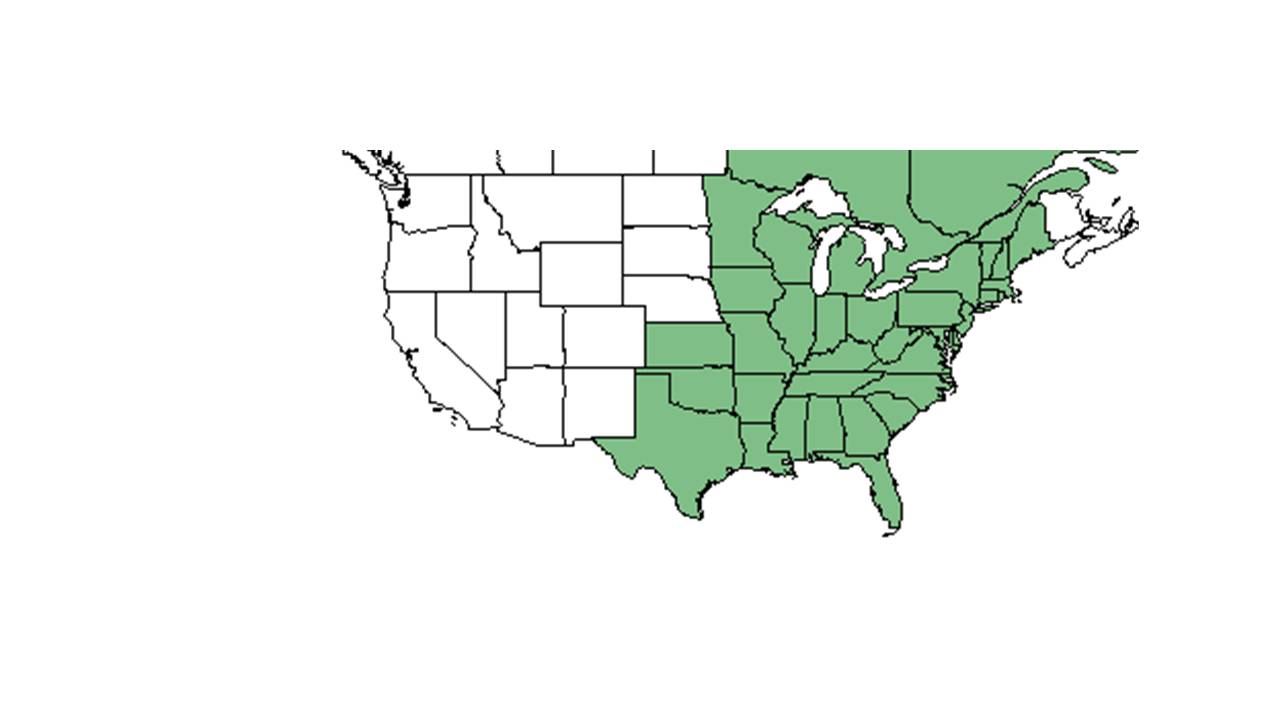

| Natural range of Hylodesmum nudiflorum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Nakedflower ticktrefoil

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Desmodium nudiflorum (Linnaeus) A.P. de Candolle; Meibomia nudiflora (Linnaeus) Kuntze

Description

Distribution

It occurs widely throughout the eastern U.S. and eastern Canada. [1]

Ecology

The aboveground parts senesce during the autumn and leaves emerge around May. Flowering starts in August, and though each flower is short-lived, flowers can develop sequentially in an inflorescence. It is a nitrogen-fixing legume.[2]

Habitat

It can live in a humid climate that experiences extremes in precipitation, wind, and temperature.[3] It is abundant in cool, temperate, continental climates with acidic, well-drained soils. It occupies areas across light and nutrient gradients, but it occurred most frequently in open and drier areas.[2][4] It is found in shortleaf pine, hickory, and oak communities.[5] Herbarium specimens[6] report its occurrence in mesic woodland, beech-magnolia woods above a permanent streamlet, Apalachicola River bluffs and ravines, pine-oak-hickory woods, pineland near small dry sinks, shortleaf pine-post oak and red oak-mockernut hickory woods, upland hardwood forest in Florida, a wooded bank in North Carolina, rocky ridges above 100 m elevation and dry, novaculate ridges above 340 m elevation in Arkansas, mixed deciduous forest and black oak wood in Michigan, shaley shaded bluffs in Virginia, limestone bluffs in Tennessee, and mesophytic woods in Kentucky. Occurs in frequently burned post-agriculture loblolly and shortleaf pine forest.[7] Light levels are generally shaded.[7] Soil types include dry sandy soil, sandy loam and rich loamy soil.[7]

Associated species include magnolia, beech, pine, oak, hickory, Mitchella repens, mockernut hickory, shortleaf pine, sweet gum, Desmodium orchroleucum, Commelina erecta, Amphicarpaea bracteata, Agrimonia, Matelea, Hexalectris, Toxicodendron, Quercus virginiana, Nyssa sylvatica, loblolly pine, and black oak.[7]

Phenology

Flowers and fruits from June to October.[7]

Seed dispersal

Animals can act as dispersal agents since the fruit coats are covered with abundant, sticky trichomes that attach to their hair.[2] It is generally not affected by dormant season (March-April) low-intensity fires since the heat generated by the fires does not penetrate to where the buds and rootstocks are. Huang and Boerner (2007) found that in their study, that burning alone or with thinning reduces nitrogen and phosphorous concentrations in the soil in the short-term and the long-term.[2] However, burning and thinning increases net photosynthesis rates of D. nudiflorum in the mixed-oak forests of Zaleski State Forest, Ohio. Mean plant biomass was also about two times greater in burned and in burned and thinned plots than in control plots. It is possible that the enhancement of photosynthesis is a result of changes in the forest floor microclimate (e.g., soil temperature, soil moisture, litter depth).[4] Also, much more nodules were found on D. nudiflorum in the burned and in burned and thinned plots than the control plots, suggesting a potential for greater nitrogen-fixing capability.[4]

Conservation and management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ NRCS Plants Database http://plants.usda.gov/java/

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Huang, J. J. and R. E. J. Boerner (2007). "Effects of fire alone or combined with thinning on tissue nutrient concentrations and nutrient resorption in Desmodium nudiflorum." Oecologia 153: 233-243.

- ↑ Chen, J., Xu, M., and Brosofske, K.D. 1997. Microclimatic characteristics in the southeastern Missouri Ozarks. In Proceedings of the Missouri Ozark Forest Ecosystem Project Symposium: An Experimental Approach to Landscape Research, St. Louis, Mo., 3–5 June 1997. Edited by B.L. Brookshire and S.R. Shifley. USDA For. Serv. Gen. Tech. Rep. GTR-NC-193. pp. 120–133.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Huang, J. J., R. E. J. Boerner, et al. (2007). "Ecophysiological responses of two herbaceous species to prescribed burning, alone or in combination with overstory thinning." American Journal of Botany 94: 755-763.

- ↑ Concilio, A., S. Y. Ma, et al. (2005). "Soil respiration response to prescribed burning and thinning in mixed-conifer and hardwood forests." Canadian Journal of Forest Research 35: 1581-1591.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedFSU Herbarium - ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: July 2015. Collectors: Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Robert K. Godfrey, Gary R. Knight, R. Kral, R. F. Thorne, R. A. Davidson, Gwen Roney, C. Jackson, K. Craddock Burks, A. F. Clewell, Robert Blaisdell, Wilson Baker, Rodie White, Billie Bailey, Marie Victorin, Rolland Germain, Ernest Rouleau, Marcel Raymond, Andre Champagne, Norland C. Henderson, R.E. Torrey, F. Hyland, Edw. Davis, William B. Fox, Delzie Demaree, B. E. Smith, Paul O. Schallert, A. E. Radford, G. W. Parmelee, Paul L. Redfearn, Jr., S.B. Jones, Carleen Jones, Mary E. Wharton, D. R. Windler, S. J. Lombardo, Michael B. Brooks, Randy Warren. States and Counties: Florida: Gadsden, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Liberty, Okaloosa, Wakulla. Georgia: Grady, Decatur. Virginia: Alleghany, Montgomery. Massachusetts: Amherst. North Carolina: Swain, Forsyth, Wayne, Jackson. Arkansas: Pulaski, Stone, Garland. South Carolina: Darlington. Michigan: Barry. Ohio: Portage. Mississippi: Smith, Webster. Missouri: McDonald, Barry. Tennessee: Lewis. Illinois: Lawrence. Kentucky: Clark. Alabama: Cherokee, Choctaw. Maryland: Baltimore. Other Countries: Canada. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.