Difference between revisions of "Lespedeza angustifolia"

(→Seed bank and germination) |

|||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

Blooms September to November (FSU Herbarium). Frequent where present by populations tend to be separated from one another.<ref name=c/> | Blooms September to November (FSU Herbarium). Frequent where present by populations tend to be separated from one another.<ref name=c/> | ||

| − | + | ===Seed dispersal=== | |

| + | According to Kay Kirkman, a plant ecologist, this species disperses by being consumed by vertebrates (being assumed). <ref name="KK"> Kay Kirkman, unpublished data, 2015. </ref> | ||

| + | |||

===Seed bank and germination=== | ===Seed bank and germination=== | ||

''Lespedeza'' and other legume species have a hard seed coat. Species with hard seed coats are likely capable of forming long-term persistent seed banks and continuation of the buried seed bag portion of this study will yield long-term data on this subject. <ref name=ck> Coffey, K. L. and L. K. Kirkman (2006). "Seed germination strategies of species with restoration potential in a fire-maintained pine savanna." Natural Areas Journal 26: 289-299. </ref> Although perennial species found in longleaf pine ecosystems, such as ''Lespedeza'', persist through frequent fire, fire exposes seeds in soil to higher temperature and high amplitudes of temperature fluctuation <ref name=g> Grime, J.P. 1989. Seed banks in ecological perspective. Pp. xv-xxii in M.A. Leck, V.T.Parker, and R.L. Simpson, eds., Ecology of Soil Seed Banks. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif. </ref> leading in some cases to germination. <ref name=ck/> | ''Lespedeza'' and other legume species have a hard seed coat. Species with hard seed coats are likely capable of forming long-term persistent seed banks and continuation of the buried seed bag portion of this study will yield long-term data on this subject. <ref name=ck> Coffey, K. L. and L. K. Kirkman (2006). "Seed germination strategies of species with restoration potential in a fire-maintained pine savanna." Natural Areas Journal 26: 289-299. </ref> Although perennial species found in longleaf pine ecosystems, such as ''Lespedeza'', persist through frequent fire, fire exposes seeds in soil to higher temperature and high amplitudes of temperature fluctuation <ref name=g> Grime, J.P. 1989. Seed banks in ecological perspective. Pp. xv-xxii in M.A. Leck, V.T.Parker, and R.L. Simpson, eds., Ecology of Soil Seed Banks. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif. </ref> leading in some cases to germination. <ref name=ck/> | ||

Revision as of 15:03, 8 April 2016

| Lespedeza angustifolia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Guy Anglin, Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae ⁄ Leguminosae |

| Genus: | Lespedeza |

| Species: | L. angustifolia |

| Binomial name | |

| Lespedeza angustifolia (Pursh) Elliott | |

| |

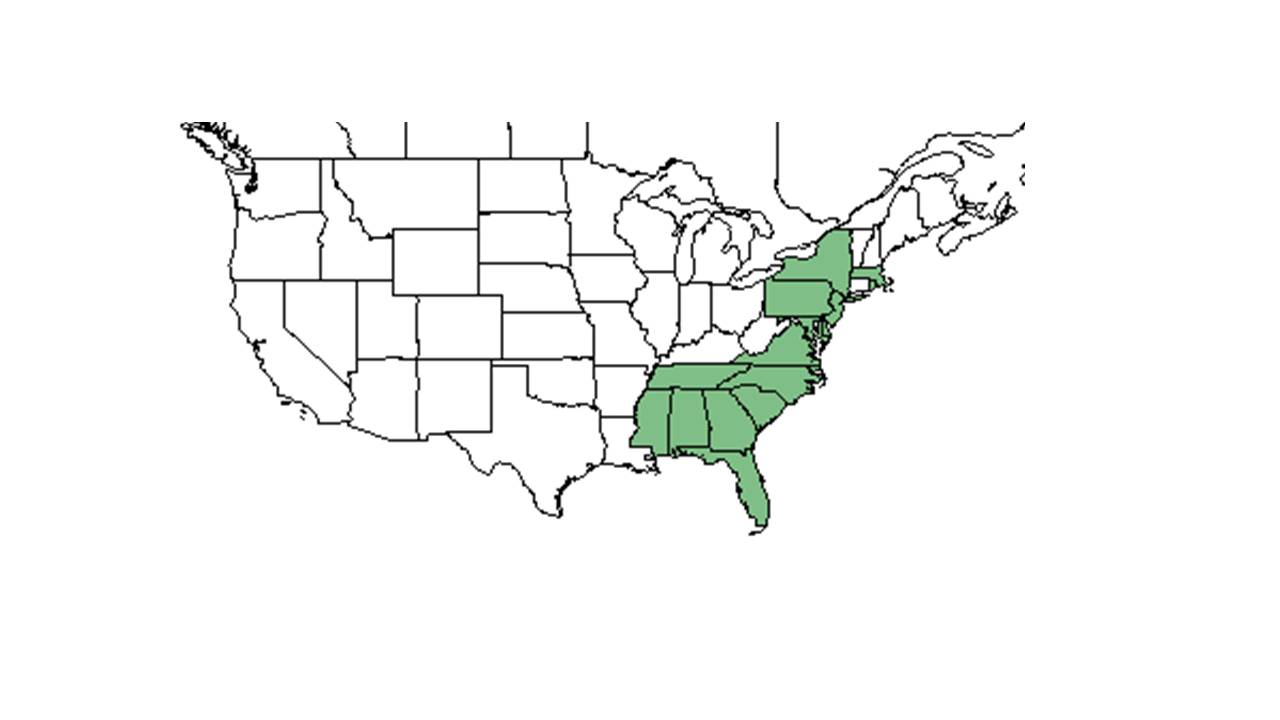

| Natural range of Lespedeza angustifolia from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: narrowleaf lespedeza

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonym: Lespedeza hirta var. intercursa Fernald

Description

“Annual or perennial herbs or shrubs. Leaves pinnately 3-folioate; leaflets entire, estipellate; stipules persistent, setaceous to ovate-lanceolate. Inflorescence usually few-to-many-flowered, loose to compact, sessile to long-pedunculate, axillary or terminal, spictate, racemose, capitate or rarely paniculate cluster; pedicels subtended by a bract and with a pair of inconspicuous bractlets immediately beneath the flower. Both apetalous (cleistogamous) and petaliferous (Chasmogamous) flowers present in most species, but the apetalous flower are more readily detected and more abundant in some species than others. Calyx persistent in fruit, the tube campanulate to cylindric with 5 nearly equal lobes or the upper 2 partly united and shorter; corolla papilionaceous, violet, purplish, roseate, yellow or whitish; stamens diadelphous, 9 and 1. Legume 1-seeded, indehiscent, sessile or stalked, flattened, elliptic, ovate or orbicular.” [1]

“Erect perennial 0.3-1.2 (1.8) m tall, above usually densely strigillose or weakly to strongly spreading, short-pubescent or even short-pilose. Densely strigillose to glabrate below. Leaflets narrowly oblong-elliptic to linear, (1.2) 2-6 cm long, 4-12X as long as wide, glabrous to more commonly densely appressed short-pubescent or strigillose above and densely strigillose beneath; stipules very narrowly linear to linear-subulate. Racemes spicate, or rarely globose, numerous, loose to compact, 0.7-3 cm long; peduncles ca. (0.5) 1-5 cm long, typically equaling or longer than the subtending leaves; peduncles and axes densely spreading short-pubescent; pedicels 1-2 mm long. Calyx densely spreading puberulent, lobes 4-6 mm long and nearly as long on the calyx; petals yellowish, the standard 5-7 mm long bearing a purplish spot. Legume densely spreading short-pubescent, broadly elliptic to oblong-obovate, 4-6 mm long, nearly equaling the calyx in length.” [1]

Distribution

Ecology

Habitat

Lespedeza angustifolia habitats include sandhills, pine flatwoods, and oldfield pinelands, as well as dry pond margins and open flood plains on areas that are mesic to excessively well drained (FSU Herbarium). It has been strongly associated with hydric habitats [2] because of a higher tolerance for periodically inundated soil conditions. [3] It has been documented to occur in dried up bottoms of sinkhole ponds (FSU Herbarium). Soils include sand and sandy loams, including Ultisols, Entisols, and dry Spodosols. [4]. Other soil types includes red sandy clay hills and sandy peat (FSU Herbarium). L. angustifolia is prevalent along eroded roadsides and railroads and in disturbed high pine habitats (FSU Herbarium). Plants associated include Aristida, Ctenium, Andropogon, Sporobolus and Panicum hemitomon (FSU Herbarium).

Phenology

Blooms September to November (FSU Herbarium). Frequent where present by populations tend to be separated from one another.[4]

Seed dispersal

According to Kay Kirkman, a plant ecologist, this species disperses by being consumed by vertebrates (being assumed). [5]

Seed bank and germination

Lespedeza and other legume species have a hard seed coat. Species with hard seed coats are likely capable of forming long-term persistent seed banks and continuation of the buried seed bag portion of this study will yield long-term data on this subject. [6] Although perennial species found in longleaf pine ecosystems, such as Lespedeza, persist through frequent fire, fire exposes seeds in soil to higher temperature and high amplitudes of temperature fluctuation [7] leading in some cases to germination. [6]

Fire ecology

Frequent dormant season burning increased legume populations in southern pine forests, although fires during the growing season at the same frequency tended to reduce legume abundance. [3] Presence of Imperata cylindrica (cogan grass), an invasive plant found in the southeastern United States, did not deter the occurrence of L. angustifolia in plots that had been burned every 1 to 2 years in southeastern Mississippi.[8] In its natural habitat it requires frequent fire for persistence. It is primarily located in undisturbed sites and sometimes colonizes frequently burned old-field pinelands.[4]

Pollination

Bee and Lepidopteran pollinated in chasmogamous flowers [4]

Conservation and Management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: July 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Wilson Baker, A. F. Clewell, James R. Coleman, Delzie Demaree, William B. Fox, J. P. Gillespie, Robert K. Godfrey, Gary R. Knight, R. Komarek, R. Kral, T. MacClendon, John Morrill, A. E. Radford, John K. Small. States and Counties: Alabama: Baldwin. Florida: Franklin, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Liberty, Madison, Nassau, Wakulla, Washington. Georgia: Appling, Baker, Camden, Clinch, Grady, Lowndes, Miller, Seminole, Thomas, Walton, Wilcox. North Carolina: Cumberland, Harnett, Pitt. South Carolina: Sumter. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 613-8. Print.

- ↑ Hainds, M. J., R. J. Mitchell, et al. (1999). "Distribution of native legumes (Leguminoseae) in frequently burned longleaf pine (Pinaceae)-wiregrass (Poaceae) ecosystems." American Journal of Botany 86: 1606-1614.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Hainds, M. J., R. J. Mitchell, et al. (1997). "Legume population dynamics in frequently burned longleaf pine-wiregrass fire ecosystem." Proceedings Longleaf Alliance Conference: Longleaf Alliance Report 1: 82-86.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Clewell, Andre. 2014. Personal observations.

- ↑ Kay Kirkman, unpublished data, 2015.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Coffey, K. L. and L. K. Kirkman (2006). "Seed germination strategies of species with restoration potential in a fire-maintained pine savanna." Natural Areas Journal 26: 289-299.

- ↑ Grime, J.P. 1989. Seed banks in ecological perspective. Pp. xv-xxii in M.A. Leck, V.T.Parker, and R.L. Simpson, eds., Ecology of Soil Seed Banks. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- ↑ Brewer, J. S. and S. P. Cralle (2003). "Phosphorus addition reduces invasion of a longleaf pine savanna (southeastern USA) by a non-indigenous grass (Imperata cylindrica)." Plant Ecology 167: 237-245.