Difference between revisions of "Phoradendron leucarpum"

KatieMccoy (talk | contribs) (→Cultivation and restoration) |

KatieMccoy (talk | contribs) (→References and notes) |

||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: [http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu]. Last accessed: October 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, J. Beckner, Kathy Craddock Burks, J. Carmichael, Nancy Edmonson, Mildred E. Feagle, Angus Gholson Jr., William T. Gillis, Robert K. Godfrey, D.W. Hall, B.K. Holst, Roy N. Jervis, Beverly Judd, Walter S. Judd, Robert L. Lazor, N. Lee, Karen MacClendon, K.M. Meyer, Chas. A. Mosier, C. Morgan, John B. Nelson, Jose Luis Serna, G.K. Small, John K. Small, A. Townesmith, Chris Wall, Randy Wall, D.B. Ward. States and Counties: Florida: Alachua, Calhoun, Collier, Franklin, Gadsden, Hernando, Highlands, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Liberty, Marion, Polk, Sarasota, Taylor, Wakulla. | Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: [http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu]. Last accessed: October 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, J. Beckner, Kathy Craddock Burks, J. Carmichael, Nancy Edmonson, Mildred E. Feagle, Angus Gholson Jr., William T. Gillis, Robert K. Godfrey, D.W. Hall, B.K. Holst, Roy N. Jervis, Beverly Judd, Walter S. Judd, Robert L. Lazor, N. Lee, Karen MacClendon, K.M. Meyer, Chas. A. Mosier, C. Morgan, John B. Nelson, Jose Luis Serna, G.K. Small, John K. Small, A. Townesmith, Chris Wall, Randy Wall, D.B. Ward. States and Counties: Florida: Alachua, Calhoun, Collier, Franklin, Gadsden, Hernando, Highlands, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Liberty, Marion, Polk, Sarasota, Taylor, Wakulla. | ||

Georgia: Decatur, Thomas. Country: Mexico. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy. | Georgia: Decatur, Thomas. Country: Mexico. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Gougherty, A. V. (2013). "Spatial distribution of eastern mistletoe phoradendron leucarpum, viscaceae in an urban environment." Journal of the Alabama Academy of Science 84(3-4): 155+. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Panvini, A. D. and W. G. Eickmeier (1993). "Nutrient and Water Relations of the Mistletoe Phoradendron leucarpum (Viscaceae): How Tightly are they Integrated?" American Journal of Botany 80(8): 872-878. | ||

Revision as of 21:04, 18 February 2016

| Phoradendron leucarpum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Mary Keim, Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Santalales |

| Family: | Viscaceae |

| Genus: | Phoradendron |

| Species: | P. leucarpum |

| Binomial name | |

| Phoradendron leucarpum (Raf.) Reveal & M.C. Johnst. | |

| |

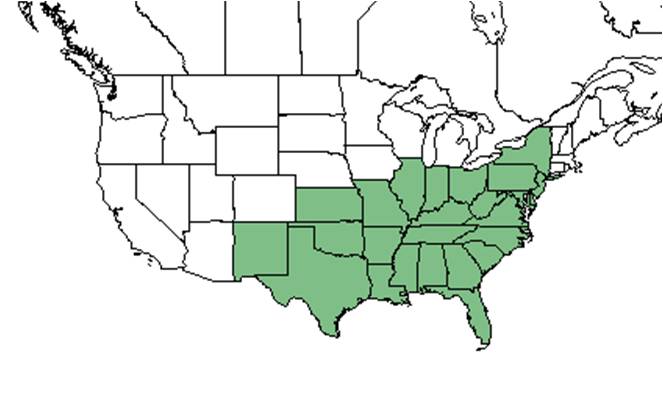

| Natural range of Phoradendron leucarpum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: oak mistletoe

Contents

Taxonomic notes

The name "mistletoe" comes from the ancient Anglo-Saxon word for dung and twig, which is derived from the observation that mistletoe often sprouts out of bird dropping on branches[1].

Description

P. leucarpum is a clumpy, evergreen shrub that can be found growing on branches of broad-leaved trees. The leaves are opposite, thick and leathery, oval to round. Flowers are small and inconspicuous and the fruits are white[1].

It is a hemiparasitic species that has chlorophyll and produces it's own food, but also has modified roots that extracts water and minerals from the host tree's circulatory system[1]. It infects more than 105 tree species: broadleaf, evergreen, deciduous, and confiers[2].

Distribution

P. leucarpum can be found on hardwood trees in the eastern United States[1].

Ecology

Habitat

Phoradendron leucarpum can be found in mixed hardwoods, cypress swamps, tupelo swamps, floodplain forests, and pine/oak scrubs. It is a parasitic plant that has been observed growing on Fraxinus, Liquidambar, Quercus nigra, Carya glabra, Prunus umbellata, Prunus angustifolia, Celtis laevigata, Quercus myrtifolia, Prunus serotina, Planera aquatica, Carya aquatica, Quercus virginiana, Acer, Morus, Populus, Ulmus and Magnolia (FSU Herbarium).

Phenology

It has been observed fruiting January, March, November and December; and flowering January, October, and December (FSU Herbarium). The ripe fruit is a transluscent, pseudo-berry, that contains viscin, which allows the seed to attach to bark[2].

Seed dispersal

The seeds are primarily dispersed by birds in excrement and regurgitation[2].

Seed bank and germination

This species does not exhibit strong seed dormancy. The translucent fruit skin must be pierced or removed to allow for seed germination[2].

Fire ecology

It has been observed in recently burned pine forests (FSU Herbarium).

Pollination

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Phoradendron leucarpum at Archbold Biological Station (Deyrup 2015):

Vespidae: Mischocyttarus cubensis

Use by animals

The fruit is eaten by birds. This plant is poisonous to humans [1].

Diseases and parasites

This species is hemiparasitic, it has chlorophyll and produces its own food, however, it has modified roots that steal water and minerals from the host tree's circulatory system[1]. It causes wood decay, branch death, discoloration and allows for animal and pathogenic entry points into a tree. It is found to infect more than 105 tree species which include broadleaf, evergreen, deciduous, and conifers. It is an obligate parasite and can not grow or survive on dead trees[2]. In a study by Panvini and Eickmeier (1993) they found that the nutrients obtained by P. leucarpum and actively aquired, meaning nutrient acquisition and water flow are not tightly coupled. They also found that P. leucarpum nutrient status was dependent upon the nutrient condition of the host tree. In another study by Gougherty (2013) it was found that larger trees have a larger mistletoe infestation. This could be due to more perching and foraging of birds.

There are pests that infect P. leucarpum, these include hickory horned-devil/royal walnut moth (Citheronia regalis) and the great blue hairstreak butterfly (Atlides halesus)[2].

Conservation and Management

Cultivation and restoration

There is a custom of kissing underneath the mistletoe. Native Americans have been thought to use infusions of mistletoe roots and berries to induce abortion and externally relieve rheumatism[1].

Photo Gallery

References and notes

Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: October 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, J. Beckner, Kathy Craddock Burks, J. Carmichael, Nancy Edmonson, Mildred E. Feagle, Angus Gholson Jr., William T. Gillis, Robert K. Godfrey, D.W. Hall, B.K. Holst, Roy N. Jervis, Beverly Judd, Walter S. Judd, Robert L. Lazor, N. Lee, Karen MacClendon, K.M. Meyer, Chas. A. Mosier, C. Morgan, John B. Nelson, Jose Luis Serna, G.K. Small, John K. Small, A. Townesmith, Chris Wall, Randy Wall, D.B. Ward. States and Counties: Florida: Alachua, Calhoun, Collier, Franklin, Gadsden, Hernando, Highlands, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Liberty, Marion, Polk, Sarasota, Taylor, Wakulla. Georgia: Decatur, Thomas. Country: Mexico. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

Gougherty, A. V. (2013). "Spatial distribution of eastern mistletoe phoradendron leucarpum, viscaceae in an urban environment." Journal of the Alabama Academy of Science 84(3-4): 155+.

Panvini, A. D. and W. G. Eickmeier (1993). "Nutrient and Water Relations of the Mistletoe Phoradendron leucarpum (Viscaceae): How Tightly are they Integrated?" American Journal of Botany 80(8): 872-878.