Difference between revisions of "Centrosema virginianum"

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

==Distribution== | ==Distribution== | ||

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

| − | ===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | + | It is a legume that has one of the highest nitrogen-fixing potentials (Cathey et al 2010). Because of this, it may be able to help restore N lost from fire (Hainds et al 1999). By mid-season in June and July, a maximum nitrogen-fixing rate was observed (Cathey et al 2010). |

| + | ===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.-->It is found in a wide range of natural and disturbed conditions, including frequently burned sandhills, upland longleaf-wiregrass and old-field pinelands (Cushwa 1966, Hainds 1999), and flatwoods, coastal island dunes and shorelines, open areas within mangrove swamps, wooded floodplains and edges of hardwood forests, and bogs . It can be found in loblolly pine communities (Cushwa 1966). It can also be found in longleaf pine-wiregrass communities (Hainds et al 1999). | ||

| + | It is tolerant of overstory canopies that decrease the light level to about half the ambient (i.e., it can live in partially shaded areas and its nitrogen-fixing capability won't be significantly affected) (Cathey et al 2010). It grows in highly disturbed areas, but it is also ubiquitous in high quality native longleaf pine uplands and sandhills. | ||

| + | It occurs in soils ranging from deep sands (Entisols) to sandy loams (Ultisols). | ||

| + | |||

===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ||

| + | It flowers in April through October and fruits primarily in June thorugh September (FSU Herbarium). | ||

===Seed dispersal=== | ===Seed dispersal=== | ||

===Seed bank and germination=== | ===Seed bank and germination=== | ||

| + | In Hier's study, changes in flowering did not seem to affect seed germination (Hiers et al 2000). It spreads clonally by production of rhizomes (Hiers et al 2007). | ||

===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ||

| + | It thrives under fire (Cushwa 1966). Hendricks observed that the Piedmont National Wildlife Refuge plots, which had been under a 4-year burning regime since 1966, each contained more than 10 times more C. virginianum individuals per ha than the Oconee National Forest plots, which had no burning history (Hendricks et al 1999). Seasonal burning does not seem to negatively affect nitrogen fixation (Hiers et al 2003). C. virginianum showed increased flowering synchrony in response to lightning-season burns (Hiers et al 2000). It responded the best to March burns with respect to annual tissue inputs as well as nitrogen contribution (Hiers et al 2003). C. virginianum showed robust flowering response to late winter/ early spring burns, supporting the response to March burns noted earlier. It has a mid-summer flowering peak (Hiers et al 2000). Also, Hiers found no evidence that increased flowering affects nitrogen-fixing capability (Hiers et al 2003). | ||

===Pollination=== | ===Pollination=== | ||

| + | Its flower is highly specialized for pollination by large Hymenoptera (Spears 1987 cited by Hiers et al 2007). It requires bees for pollination to "trip" the pollen delivery mechanism. Pollinator-plant relationships appear to be robust to alteration in flowering phenology resulting from variation in season of burn (Hiers et al 2000). | ||

===Use by animals=== <!--Herbivory, granivory, insect hosting, etc.--> | ===Use by animals=== <!--Herbivory, granivory, insect hosting, etc.--> | ||

| + | Because C. virginianum is a legume, and legumes are high in protein and mineral content, a number of herbivores including but not limited to Gopherus polyphemus, white-tailed deer, and bob-white quail, consume it (Hainds et al 1999). | ||

===Diseases and parasites=== | ===Diseases and parasites=== | ||

==Conservation and Management== | ==Conservation and Management== | ||

| Line 33: | Line 42: | ||

==Photo Gallery== | ==Photo Gallery== | ||

==References and notes== | ==References and notes== | ||

| + | FSU herbarium herbarium.bio.fsu.edu | ||

| + | |||

| + | Cushwa, C. T. (1966). The response of herbaceous vegetation to prescribed burning. Asheville, USDA Forest Service. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hainds, M. J., R. J. Mitchell, et al. (1999). "Distribution of native legumes (Leguminoseae) in frequently burned longleaf pine (Pinaceae)-wiregrass (Poaceae) ecosystems." American Journal of Botany 86: 1606-1614. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Cathey, S. E., L. R. Boring, et al. (2010). "Assessment of N2 fixation capability of native legumes from the longleaf pine-wiregrass ecosystem." Environmental and Experimental Botany 67: 444-450. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hiers, J. K. and R. J. Mitchell (2007). "The influence of burning and light availability on N-2-fixation of native legumes in longleaf pine woodlands." Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 134: 398-409. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Spears, Jr. E. E. 1987. Island and mainland | ||

| + | pollination ecology of Centrosema virginianum and Opuntia s trie ta. J. Ecol. 75: 351-362. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hendricks, J. J. and L. R. Boring (1999). "N2-fixation by native herbaceous legumes in burned pine ecosystems of the southeastern United States." Forest Ecology and Management 113: 167-177. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hiers, J. K., R. J. Mitchell, et al. (2003). "Legumes native to longleaf pine savannas exhibit capacity for high N2-fixation rates and negligible impacts due to timing of fire." New Phytologist 157: 327-338. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hiers, J. K., R. Wyatt, et al. (2000). "The effects of fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas: is a season selective?" Oecologia 125: 521-530. | ||

Revision as of 14:11, 26 June 2015

| Centrosema virginianum | |

|---|---|

| |

| photo by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae ⁄ Leguminosae |

| Genus: | Centrosema |

| Species: | C. virginianum |

| Binomial name | |

| Centrosema virginianum (L.) Benth. | |

| |

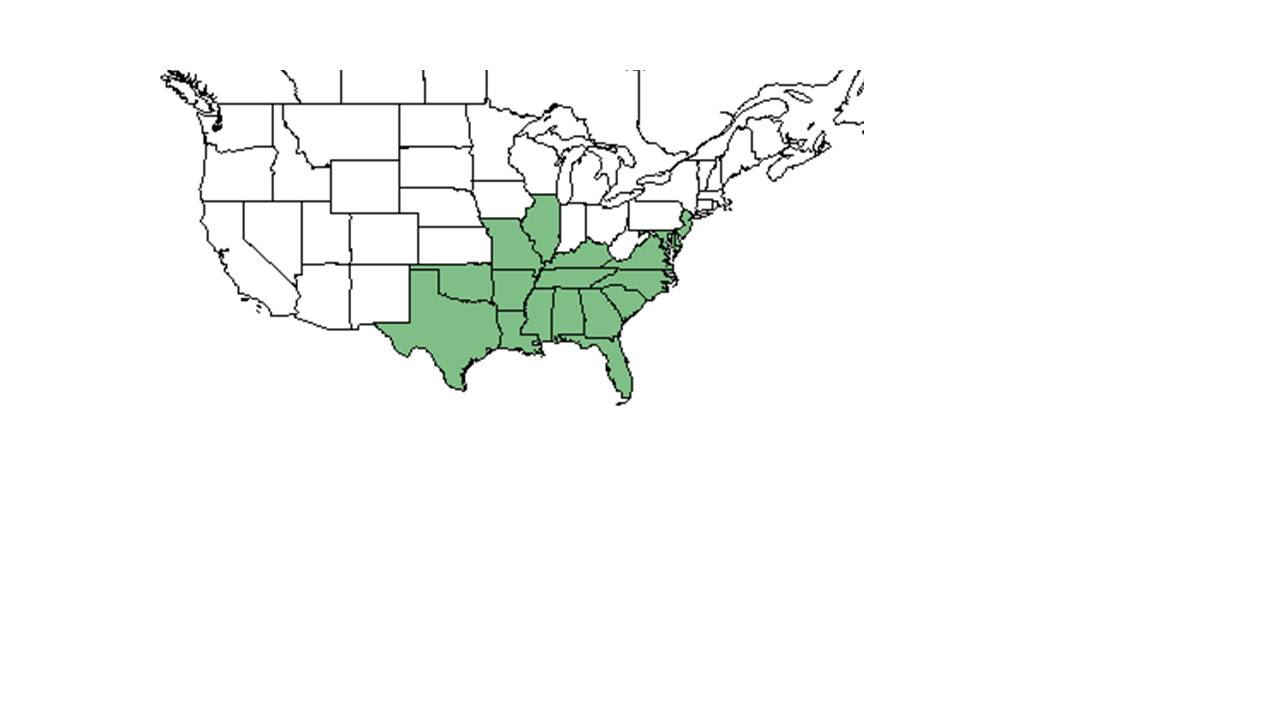

| Natural range of Centrosema virginianum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Description

Distribution

Ecology

It is a legume that has one of the highest nitrogen-fixing potentials (Cathey et al 2010). Because of this, it may be able to help restore N lost from fire (Hainds et al 1999). By mid-season in June and July, a maximum nitrogen-fixing rate was observed (Cathey et al 2010). ===Habitat=== It is found in a wide range of natural and disturbed conditions, including frequently burned sandhills, upland longleaf-wiregrass and old-field pinelands (Cushwa 1966, Hainds 1999), and flatwoods, coastal island dunes and shorelines, open areas within mangrove swamps, wooded floodplains and edges of hardwood forests, and bogs . It can be found in loblolly pine communities (Cushwa 1966). It can also be found in longleaf pine-wiregrass communities (Hainds et al 1999). It is tolerant of overstory canopies that decrease the light level to about half the ambient (i.e., it can live in partially shaded areas and its nitrogen-fixing capability won't be significantly affected) (Cathey et al 2010). It grows in highly disturbed areas, but it is also ubiquitous in high quality native longleaf pine uplands and sandhills. It occurs in soils ranging from deep sands (Entisols) to sandy loams (Ultisols).

Phenology

It flowers in April through October and fruits primarily in June thorugh September (FSU Herbarium).

Seed dispersal

Seed bank and germination

In Hier's study, changes in flowering did not seem to affect seed germination (Hiers et al 2000). It spreads clonally by production of rhizomes (Hiers et al 2007).

Fire ecology

It thrives under fire (Cushwa 1966). Hendricks observed that the Piedmont National Wildlife Refuge plots, which had been under a 4-year burning regime since 1966, each contained more than 10 times more C. virginianum individuals per ha than the Oconee National Forest plots, which had no burning history (Hendricks et al 1999). Seasonal burning does not seem to negatively affect nitrogen fixation (Hiers et al 2003). C. virginianum showed increased flowering synchrony in response to lightning-season burns (Hiers et al 2000). It responded the best to March burns with respect to annual tissue inputs as well as nitrogen contribution (Hiers et al 2003). C. virginianum showed robust flowering response to late winter/ early spring burns, supporting the response to March burns noted earlier. It has a mid-summer flowering peak (Hiers et al 2000). Also, Hiers found no evidence that increased flowering affects nitrogen-fixing capability (Hiers et al 2003).

Pollination

Its flower is highly specialized for pollination by large Hymenoptera (Spears 1987 cited by Hiers et al 2007). It requires bees for pollination to "trip" the pollen delivery mechanism. Pollinator-plant relationships appear to be robust to alteration in flowering phenology resulting from variation in season of burn (Hiers et al 2000).

Use by animals

Because C. virginianum is a legume, and legumes are high in protein and mineral content, a number of herbivores including but not limited to Gopherus polyphemus, white-tailed deer, and bob-white quail, consume it (Hainds et al 1999).

Diseases and parasites

Conservation and Management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

FSU herbarium herbarium.bio.fsu.edu

Cushwa, C. T. (1966). The response of herbaceous vegetation to prescribed burning. Asheville, USDA Forest Service.

Hainds, M. J., R. J. Mitchell, et al. (1999). "Distribution of native legumes (Leguminoseae) in frequently burned longleaf pine (Pinaceae)-wiregrass (Poaceae) ecosystems." American Journal of Botany 86: 1606-1614.

Cathey, S. E., L. R. Boring, et al. (2010). "Assessment of N2 fixation capability of native legumes from the longleaf pine-wiregrass ecosystem." Environmental and Experimental Botany 67: 444-450.

Hiers, J. K. and R. J. Mitchell (2007). "The influence of burning and light availability on N-2-fixation of native legumes in longleaf pine woodlands." Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 134: 398-409.

Spears, Jr. E. E. 1987. Island and mainland pollination ecology of Centrosema virginianum and Opuntia s trie ta. J. Ecol. 75: 351-362.

Hendricks, J. J. and L. R. Boring (1999). "N2-fixation by native herbaceous legumes in burned pine ecosystems of the southeastern United States." Forest Ecology and Management 113: 167-177.

Hiers, J. K., R. J. Mitchell, et al. (2003). "Legumes native to longleaf pine savannas exhibit capacity for high N2-fixation rates and negligible impacts due to timing of fire." New Phytologist 157: 327-338.

Hiers, J. K., R. Wyatt, et al. (2000). "The effects of fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas: is a season selective?" Oecologia 125: 521-530.