Difference between revisions of "Tephrosia virginiana"

Krobertson (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (62 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

==Taxonomic Notes== | ==Taxonomic Notes== | ||

| − | + | Synonyms: ''Cracca virginiana'' Linnaeus.<ref>Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draf of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.</ref> | |

| − | + | ||

| + | Variations: ''T. virginiana'' var. ''glabra'' Nuttall.<ref>Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draf of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.</ref> | ||

==Description== <!-- Basic life history facts such as annual/perrenial, monoecious/dioecious, root morphology, seed type, etc. --> | ==Description== <!-- Basic life history facts such as annual/perrenial, monoecious/dioecious, root morphology, seed type, etc. --> | ||

| − | ''Tephrosia virginiana'' is covered with soft white hairs, which makes it silvery green in appearance. It grows to 1-3 ft (0.30-0.91 m) and has long stringy roots, from which it gets the name devil's shoestring. Leaves are pinnately compound with 8-15 pairs of leaflets. Flowers are bi-colored with pink and pale yellow and typically cluster at the tip of the stem. In southern portions of its range, flowers can initially be white but will change over time.<ref name="Ladybird"/> | + | ''Tephrosia virginiana'' is covered with soft white hairs, which makes it silvery green in appearance. It grows to 1-3 ft (0.30-0.91 m) and has long stringy roots, from which it gets the name devil's shoestring. Leaves are pinnately compound with 8-15 pairs of leaflets. Flowers are bi-colored with pink and pale yellow and typically cluster at the tip of the stem. In southern portions of its range, flowers can initially be white but will change over time.<ref name="Ladybird"/> ''T. virgininana'' is hard seeded, thus requiring scarification.<ref name="Wiggers et al 2013">Wiggers MS, Kirkman LK, Boyd RS, Hiers JK (2013) Fine-scale variation in surface fire environment and legume germination in the longleaf pine ecosystem. Forest Ecology and Management 310:54-63.</ref> |

==Distribution== | ==Distribution== | ||

| Line 31: | Line 32: | ||

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ||

| − | ''T. virginiana'' is found in | + | ''T. virginiana'' is found in sandhill and clayhill longleaf pine communities, other pinelands, xeric or rocky woodlands and forests, outcrops, shale barrens, other barrens, and dry roadbanks.<ref name="Weakley 2015"/> In South Carolina, it was found in 72% of forest sites, 0% of pastures, and 8% of cultivated fields.<ref name="Brudvig & Damschen 2011">Brudvig LA, Damschen EI (2011) Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34:257-266.</ref> ''T. virginiana'' is considered a characteristic legume species of shortleaf pine-oak-hickory woodlands<ref name="Clewell 2013">Clewell AF (2013) Prior prevalence of shortleaf pine-oak-hickory woodlands in the Tallahassee red hills. Castanea 78(4):266-276.</ref> and longleaf pine/wiregrass communities.<ref name="Andreu et al 2009">Andreu MG, Hedman CW, Friedman MH, Andreu AG (2009) Can managers bank on seed banks when restoring ''Pinus taeda'' L. plantations in southwest Georgia? Restoration Ecology 17(5):586-596.</ref> It is considered indicative of non-agricultural history on frequently burned longleaf pine habitats.<ref name= "Hahn"/> ''T. virginiana'' has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished longleaf pine habitat that was disturbed by agriculture in South Carolina longleaf pine woodlands and southwest Georgia pine forests, making it a remnant woodland indicator.<ref name="Brudvig & Damschen 2011"/><ref name=brudvig13> Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.</ref><ref name=brudvig14>Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.</ref><ref name=hedman>Hedman, C.W., S.L. Grace, and S.E. King. (2000). Vegetation composition and structure of southern coastal plain pine forests: an ecological comparison. Forest Ecology and Management 134:233-247.</ref><ref name=kirkman>Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.</ref><ref name="Ostertag">Ostertag, T. E. and K. M. Robertson 2007. A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, South Georgia, USA. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings 23:109-120.</ref> Additionally, a study exploring longleaf pine patch dynamics found ''T. virginiana'' to be most strongly represented within stands of longleaf pine that are between 50-90 years of age.<ref>Mugnani et al. (2019). “Longleaf Pine Patch Dynamics Influence Ground-Layer Vegetation in Old-Growth Pine Savanna”.</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | Associated species: ''Rhus, Cornus, Rosa, Amorpha, Wisteria, Euphorbia, Smilax, Prunella, Triodanis, Andropogon gerardii'', and ''Sambuscus''.<ref name="STAR"> Arkansas State University accessed using Southeastern Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) data portal. URL: http://sernecportal.org/portal/collections/index.php Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: E. L. Richards. States and Counties: Arkansas: Poinsett.</ref><ref name="AUA"> Auburn University, John D. Freeman Herbarium accessed using Southeastern Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) data portal. URL: http://sernecportal.org/portal/collections/index.php Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: G. Gil, M. Gil, and E.L. Richards. States and Counties: Alabama: Barbour and Russell.</ref><ref name="APSC"> Austin Peay State University Herbarium accessed using Southeastern Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) data portal. URL: http://sernecportal.org/portal/collections/index.php Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: Dwayne Estes. States and Counties: Tennessee: Giles.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Massachusetts it is one of several species positively associated with ''Linum intercursum'' and ''[[Scleria pauciflora]]''.<ref name="Clarke & Patterson 2007">Clarke GL, Patterson WA III (2007) The distribution of disturbance-dependent rare plants in a coastal Massachusetts sandplain: Implications for conservation and management. Biological Conservation 136:4-16.</ref> | ||

===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ||

| − | + | ''T. virginiana'' has been observed to flower April through June.<ref name="Weakley 2015"/><ref name="PanFlora">Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 12 JAN 2018</ref> Fruiting occurs from July through October.<ref name="Weakley 2015"/> Germination occurs from March through June when seasonal temperatures are increasing.<ref name="Coffey & Kirkman 2006"/> Flowering is stimulated by fire and occurs within three months of burning.<ref name="Robertson">Robertson, K. 2015. personal observation at Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, near Thomasville, Georgia.</ref> | |

<!--===Seed dispersal===--> | <!--===Seed dispersal===--> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ===Seed bank and germination=== |

| − | ''T. virginiana'' comprises 2-5% of the diets of some large mammals and terrestrial birds.<ref name="Miller & Miller 1999">Miller JH, Miller KV (1999) Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.</ref> | + | This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity.<ref> Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.</ref> In Georgia, seeds buried in a seed bag for 1 and 2 years showed 61% and 50% germination rates, respectively.<ref name="Coffey & Kirkman 2006">Coffey KL, Kirkman LK (2006) Seed germination strategies of species with restoration potential in a fire-maintained pine savanna. Natural Areas Journal 26(3):289-299.</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | ===Fire ecology=== | ||

| + | Populations have been known to persist through repeated annual burns,<ref>Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.</ref> and''Tephrosia virginiana'' re-sprouts rapidly following fire and flowers within three months of burning.<ref name="Robertson"/> A study describing the effects of a seasonal fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas found that ''T. virginiana'' produced the greatest number of flowers after a late winter/early spring burn (188.3) with the number of flowers decreasing slightly after a lightning season burn (107.1) and dropping significantly after an instance of no fire (23.4).<ref>Hiers, J. K., et al. (2000). "The effects of fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas: is a season selective?" Oecologia 125: 521-530.</ref> This study also found that the duration of synchronous flowering was greatest after an instance of no fire (37.7 days) and decreased after a late winter/early spring burn (32.0 days) and after a lighting season burn (29.0 days).<ref>Hiers, J. K., et al. (2000). "The effects of fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas: is a season selective?" Oecologia 125: 521-530.</ref> Additionally, peak flowering activity occurred earliest after an instance of no fire (121.3 Julian) with peak flowering occurring later after a late winter/early spring burn (148.7 Julian) and after a lighting season burn (206.0 Julian).<ref>Hiers, J. K., et al. (2000). "The effects of fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas: is a season selective?" Oecologia 125: 521-530.</ref> Burning has also been shown to decrease the percentage of seeds that germinate. However, this is only true when course fuels (e.g. pine cones), and not fine fuels (e.g. pine needles), are consumed. Models suggest these course fuels produce mortality close to the fuel but fails to scarify seeds further away; this leaves an area between the two where scarification and germination can occur.<ref name="Wiggers et al 2013"/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Pollination=== | ||

| + | ''Tephrosia virginiana'' has been observed to host pollinator species such as ''Calliopsis andreniformis'' (family Andrenidae), pollinators from the Apidae family such as ''Ceratina strenua, Holcopasites calliopsidis'' and ''Xylocopa virginica'', pollinators from the Halictidae family such as ''Agapostemon texanus, A. virescens, Halictus confusus, H. ligatus, Lasioglossum acuminatum, L. coriaceum, L. cressonii, L. leucocomum, L. leucozonium, L. pectorale'' and ''L. tegulare'', pollinators from the Megachilidae family such as ''Coelioxys porterae, C. sayi, Hoplitis pilosifrons, H. truncata, Megachile addenda, M. brevis, M. exilis, M. frugalis, M. gemula, M. georgica, M. mendica, M. montivaga, M. mucida, M. texana, Osmia atriventris'' and ''O. sandhouseae,''.<ref>Discoverlife.org [https://www.discoverlife.org/20/q?search=Bidens+albaDiscoverlife.org|Discoverlife.org]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Herbivory and toxicology=== <!--Common herbivores, granivory, insect hosting, poisonous chemicals, allelopathy, etc.--> | ||

| + | ''T. virginiana'' comprises 2-5% of the diets of some large mammals and terrestrial birds.<ref name="Miller & Miller 1999">Miller JH, Miller KV (1999) Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.</ref> Common grasshoppers, including ''Melanopus angustipennis'' and grasshoppers in the subfamilies Melanoplinae and Cyrtacanthacridinae, are mixed feeders and found to feed on this plant. However, herbivory did not affect overall biomass or mortality of the plant.<ref name= "Hahn">Hahn, P. C. and J. L. Orrock (2015). "Land-use legacies and present fire regimes interact to mediate herbivory by altering the neighboring plant community." Oikos 124: 497-506.</ref> In the past, it was used as a goat feed to increase milk production. However, this use stopped after tephrosin, an insecticide and fish poison, was found in it.<ref name="Ladybird"/> | ||

<!--==Diseases and parasites==--> | <!--==Diseases and parasites==--> | ||

| − | ==Conservation and Management== | + | ==Conservation, cultivation, and restoration== |

| + | ''Tephrosia virginiana'' appears to be sensitive to soil disturbance, such that disturbances including disking and roller chopping should be avoided to maintain its populations.<ref>Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.</ref><ref>Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.</ref><ref>Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.</ref><ref>Hedman, C.W., S.L. Grace, and S.E. King. (2000). Vegetation composition and structure of southern coastal plain pine forests: an ecological comparison. Forest Ecology and Management 134:233-247.</ref><ref>Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.</ref><ref name="Ostertag"/> It appears to depend on at least periodic fire in southeastern U.S. pine communities.<ref name="Hiers"/> | ||

| + | Seeds can be collected from August to September. Seeds should be scarified, inoculated, and moist stratified for ten days to stimulate germination.<ref name="Ladybird"/> This species should avoid soil disturbance by agriculture to conserve its presence in pine communities.<ref name="Brudvig & Damschen 2011"/><ref name=brudvig13/><ref name=brudvig14/><ref name=hedman/><ref name=kirkman/><ref name="Ostertag"/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Cultural use== | ||

| + | The exact toxicity of ''Tephrosia virginiana'' is not fully understood, though there have been reports that the seeds and wood of this species are toxic. Caution should be taken when using this species until more is known.<ref>Hardin, J.W. 1961. Poisonous Plants of North Carolina. North Carolina State College, Raleigh, North Carolina.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Historically, Native Americans used the plant for a variety of applications. It was used as a fish poison<ref> Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.</ref>, women would use it as a shampoo to prevent hair loss, and a decoction was applied to the body for athletic strength. Medicinally, the plant can be considered a tonic, stimulant, and laxative, and it is used to treat syphilis, worms, bladder issues, and chronic coughing.<ref> Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.</ref> | ||

| − | |||

==Photo Gallery== | ==Photo Gallery== | ||

<gallery widths=180px> | <gallery widths=180px> | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

==References and notes== | ==References and notes== | ||

Latest revision as of 11:20, 8 November 2022

| Tephrosia virginiana | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Genus: | Tephrosia |

| Species: | T. virginiana |

| Binomial name | |

| Tephrosia virginiana (L.) Pers. | |

| |

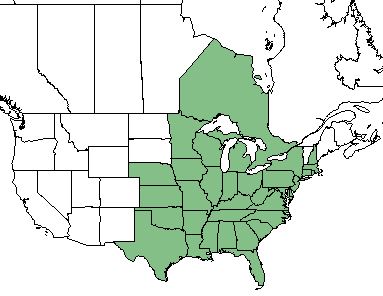

| Natural range of Tephrosia virginiana from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common Name(s): Virginia goat's-rue;[1] Virginia tephrosia;[2][3] goat's rue; devil's shoestring[3]

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: Cracca virginiana Linnaeus.[4]

Variations: T. virginiana var. glabra Nuttall.[5]

Description

Tephrosia virginiana is covered with soft white hairs, which makes it silvery green in appearance. It grows to 1-3 ft (0.30-0.91 m) and has long stringy roots, from which it gets the name devil's shoestring. Leaves are pinnately compound with 8-15 pairs of leaflets. Flowers are bi-colored with pink and pale yellow and typically cluster at the tip of the stem. In southern portions of its range, flowers can initially be white but will change over time.[3] T. virgininana is hard seeded, thus requiring scarification.[6]

Distribution

This species is found from Texas, eastward to Florida, northward to New Hampshire and New York, and inland to Minnesota and Nebraska.[1][2] It is also reported to occur in the Ontario province of Canada.[2]

Ecology

Habitat

T. virginiana is found in sandhill and clayhill longleaf pine communities, other pinelands, xeric or rocky woodlands and forests, outcrops, shale barrens, other barrens, and dry roadbanks.[1] In South Carolina, it was found in 72% of forest sites, 0% of pastures, and 8% of cultivated fields.[7] T. virginiana is considered a characteristic legume species of shortleaf pine-oak-hickory woodlands[8] and longleaf pine/wiregrass communities.[9] It is considered indicative of non-agricultural history on frequently burned longleaf pine habitats.[10] T. virginiana has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished longleaf pine habitat that was disturbed by agriculture in South Carolina longleaf pine woodlands and southwest Georgia pine forests, making it a remnant woodland indicator.[7][11][12][13][14][15] Additionally, a study exploring longleaf pine patch dynamics found T. virginiana to be most strongly represented within stands of longleaf pine that are between 50-90 years of age.[16]

Associated species: Rhus, Cornus, Rosa, Amorpha, Wisteria, Euphorbia, Smilax, Prunella, Triodanis, Andropogon gerardii, and Sambuscus.[17][18][19]

In Massachusetts it is one of several species positively associated with Linum intercursum and Scleria pauciflora.[20]

Phenology

T. virginiana has been observed to flower April through June.[1][21] Fruiting occurs from July through October.[1] Germination occurs from March through June when seasonal temperatures are increasing.[22] Flowering is stimulated by fire and occurs within three months of burning.[23]

Seed bank and germination

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity.[24] In Georgia, seeds buried in a seed bag for 1 and 2 years showed 61% and 50% germination rates, respectively.[22]

Fire ecology

Populations have been known to persist through repeated annual burns,[25] andTephrosia virginiana re-sprouts rapidly following fire and flowers within three months of burning.[23] A study describing the effects of a seasonal fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas found that T. virginiana produced the greatest number of flowers after a late winter/early spring burn (188.3) with the number of flowers decreasing slightly after a lightning season burn (107.1) and dropping significantly after an instance of no fire (23.4).[26] This study also found that the duration of synchronous flowering was greatest after an instance of no fire (37.7 days) and decreased after a late winter/early spring burn (32.0 days) and after a lighting season burn (29.0 days).[27] Additionally, peak flowering activity occurred earliest after an instance of no fire (121.3 Julian) with peak flowering occurring later after a late winter/early spring burn (148.7 Julian) and after a lighting season burn (206.0 Julian).[28] Burning has also been shown to decrease the percentage of seeds that germinate. However, this is only true when course fuels (e.g. pine cones), and not fine fuels (e.g. pine needles), are consumed. Models suggest these course fuels produce mortality close to the fuel but fails to scarify seeds further away; this leaves an area between the two where scarification and germination can occur.[6]

Pollination

Tephrosia virginiana has been observed to host pollinator species such as Calliopsis andreniformis (family Andrenidae), pollinators from the Apidae family such as Ceratina strenua, Holcopasites calliopsidis and Xylocopa virginica, pollinators from the Halictidae family such as Agapostemon texanus, A. virescens, Halictus confusus, H. ligatus, Lasioglossum acuminatum, L. coriaceum, L. cressonii, L. leucocomum, L. leucozonium, L. pectorale and L. tegulare, pollinators from the Megachilidae family such as Coelioxys porterae, C. sayi, Hoplitis pilosifrons, H. truncata, Megachile addenda, M. brevis, M. exilis, M. frugalis, M. gemula, M. georgica, M. mendica, M. montivaga, M. mucida, M. texana, Osmia atriventris and O. sandhouseae,.[29]

Herbivory and toxicology

T. virginiana comprises 2-5% of the diets of some large mammals and terrestrial birds.[30] Common grasshoppers, including Melanopus angustipennis and grasshoppers in the subfamilies Melanoplinae and Cyrtacanthacridinae, are mixed feeders and found to feed on this plant. However, herbivory did not affect overall biomass or mortality of the plant.[10] In the past, it was used as a goat feed to increase milk production. However, this use stopped after tephrosin, an insecticide and fish poison, was found in it.[3]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Tephrosia virginiana appears to be sensitive to soil disturbance, such that disturbances including disking and roller chopping should be avoided to maintain its populations.[31][32][33][34][35][15] It appears to depend on at least periodic fire in southeastern U.S. pine communities.[36] Seeds can be collected from August to September. Seeds should be scarified, inoculated, and moist stratified for ten days to stimulate germination.[3] This species should avoid soil disturbance by agriculture to conserve its presence in pine communities.[7][11][12][13][14][15]

Cultural use

The exact toxicity of Tephrosia virginiana is not fully understood, though there have been reports that the seeds and wood of this species are toxic. Caution should be taken when using this species until more is known.[37]

Historically, Native Americans used the plant for a variety of applications. It was used as a fish poison[38], women would use it as a shampoo to prevent hair loss, and a decoction was applied to the body for athletic strength. Medicinally, the plant can be considered a tonic, stimulant, and laxative, and it is used to treat syphilis, worms, bladder issues, and chronic coughing.[39]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley A. S.(2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 12 January 2018). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Plant database: Tephrosia virginiana. (12 January 2018) Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. URL: https://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=TEVI

- ↑ Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draf of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draf of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Wiggers MS, Kirkman LK, Boyd RS, Hiers JK (2013) Fine-scale variation in surface fire environment and legume germination in the longleaf pine ecosystem. Forest Ecology and Management 310:54-63.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Brudvig LA, Damschen EI (2011) Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34:257-266.

- ↑ Clewell AF (2013) Prior prevalence of shortleaf pine-oak-hickory woodlands in the Tallahassee red hills. Castanea 78(4):266-276.

- ↑ Andreu MG, Hedman CW, Friedman MH, Andreu AG (2009) Can managers bank on seed banks when restoring Pinus taeda L. plantations in southwest Georgia? Restoration Ecology 17(5):586-596.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Hahn, P. C. and J. L. Orrock (2015). "Land-use legacies and present fire regimes interact to mediate herbivory by altering the neighboring plant community." Oikos 124: 497-506.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Hedman, C.W., S.L. Grace, and S.E. King. (2000). Vegetation composition and structure of southern coastal plain pine forests: an ecological comparison. Forest Ecology and Management 134:233-247.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Ostertag, T. E. and K. M. Robertson 2007. A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, South Georgia, USA. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings 23:109-120.

- ↑ Mugnani et al. (2019). “Longleaf Pine Patch Dynamics Influence Ground-Layer Vegetation in Old-Growth Pine Savanna”.

- ↑ Arkansas State University accessed using Southeastern Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) data portal. URL: http://sernecportal.org/portal/collections/index.php Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: E. L. Richards. States and Counties: Arkansas: Poinsett.

- ↑ Auburn University, John D. Freeman Herbarium accessed using Southeastern Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) data portal. URL: http://sernecportal.org/portal/collections/index.php Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: G. Gil, M. Gil, and E.L. Richards. States and Counties: Alabama: Barbour and Russell.

- ↑ Austin Peay State University Herbarium accessed using Southeastern Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) data portal. URL: http://sernecportal.org/portal/collections/index.php Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: Dwayne Estes. States and Counties: Tennessee: Giles.

- ↑ Clarke GL, Patterson WA III (2007) The distribution of disturbance-dependent rare plants in a coastal Massachusetts sandplain: Implications for conservation and management. Biological Conservation 136:4-16.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 12 JAN 2018

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Coffey KL, Kirkman LK (2006) Seed germination strategies of species with restoration potential in a fire-maintained pine savanna. Natural Areas Journal 26(3):289-299.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Robertson, K. 2015. personal observation at Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, near Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Hiers, J. K., et al. (2000). "The effects of fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas: is a season selective?" Oecologia 125: 521-530.

- ↑ Hiers, J. K., et al. (2000). "The effects of fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas: is a season selective?" Oecologia 125: 521-530.

- ↑ Hiers, J. K., et al. (2000). "The effects of fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas: is a season selective?" Oecologia 125: 521-530.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- ↑ Miller JH, Miller KV (1999) Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.

- ↑ Hedman, C.W., S.L. Grace, and S.E. King. (2000). Vegetation composition and structure of southern coastal plain pine forests: an ecological comparison. Forest Ecology and Management 134:233-247.

- ↑ Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHiers - ↑ Hardin, J.W. 1961. Poisonous Plants of North Carolina. North Carolina State College, Raleigh, North Carolina.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.

- ↑ Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.