Difference between revisions of "Vaccinium arboreum"

(→Habitat) |

HaleighJoM (talk | contribs) (→Ecology) |

||

| (7 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

<!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ||

| − | ''V. arboreum'' reduced its occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in South Carolina's longleaf communities | + | ''V. arboreum'' reduced its occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in South Carolina's longleaf communities.<ref>Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.</ref> It has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished pinelands that were disturbed by agriculture, making it a possible indicator species for remnant woodlands.<ref>Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.</ref> It became absent in response to military training in west Georgia pinelands.<ref>Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.</ref> This species does not respond to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in north Florida flatwoods forests.<ref>Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.</ref> |

''Vaccinium arboreum'' is frequent and abundant in the North Florida Longleaf Woodlands and Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).<ref>Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.</ref> | ''Vaccinium arboreum'' is frequent and abundant in the North Florida Longleaf Woodlands and Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).<ref>Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.</ref> | ||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

<!--===Seed bank and germination===--> | <!--===Seed bank and germination===--> | ||

===Fire ecology=== | ===Fire ecology=== | ||

| − | ''V. arboreum'' has a medium tolerance of fire | + | ''V. arboreum'' has a medium tolerance of fire,<ref name= "USDA"> [https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=CEAM USDA Plant Database]</ref> but populations have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.<ref>Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.</ref><ref>Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.</ref><ref>Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.</ref> |

Given ''V. arboreum'' is usually maintained by fire, when the habitat is fire suppressed the species will grow to maturity and taller than in fire maintained regions.<ref name= "Weakley"> Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.</ref><ref name="rodger">Rodgers, H. L. and L. Provencher (1999). "Analysis of Longleaf Pine Sandhill Vegetation in Northwest Florida." Castanea 64(2): 138-162.</ref> | Given ''V. arboreum'' is usually maintained by fire, when the habitat is fire suppressed the species will grow to maturity and taller than in fire maintained regions.<ref name= "Weakley"> Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.</ref><ref name="rodger">Rodgers, H. L. and L. Provencher (1999). "Analysis of Longleaf Pine Sandhill Vegetation in Northwest Florida." Castanea 64(2): 138-162.</ref> | ||

<!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ||

| − | ===Pollination | + | ===Pollination=== |

''V. arboreum'' has been observed to host pollinators such as ''Colletes thoracicus'' (family Colletidae) and ''Osmia inspergens'' (family Megachilidae).<ref>Discoverlife.org [https://www.discoverlife.org/20/q?search=Bidens+albaDiscoverlife.org|Discoverlife.org]</ref> | ''V. arboreum'' has been observed to host pollinators such as ''Colletes thoracicus'' (family Colletidae) and ''Osmia inspergens'' (family Megachilidae).<ref>Discoverlife.org [https://www.discoverlife.org/20/q?search=Bidens+albaDiscoverlife.org|Discoverlife.org]</ref> | ||

| − | <!--==Diseases and parasites==--> | + | <!--===Herbivory and toxicology=== <!--Common herbivores, granivory, insect hosting, poisonous chemicals, allelopathy, etc.--> |

| + | <!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | ||

==Conservation, cultivation, and restoration== | ==Conservation, cultivation, and restoration== | ||

Latest revision as of 17:12, 18 July 2022

Common names: farkleberry[1], sparkleberry[2], winter huckleberry[3], tree sparkleberry[4], tree huckleberry[5]

| Vaccinium arboreum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John Hilty hosted at IllinoisWildflowers.info | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Ericales |

| Family: | Ericaceae |

| Genus: | Vaccinium |

| Species: | V. arboreum |

| Binomial name | |

| Vaccinium arboreum Marshall | |

| |

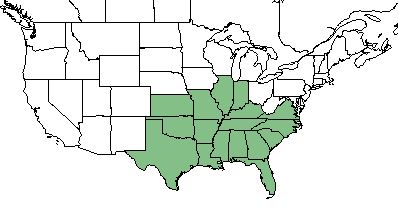

| Natural range of Vaccinium arboreum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonym: Batodendron arboreum (Marshall) Nuttall.[6]

Varieties: V. arboreum var. glaucescens (Greene) Sargent.[7]

Description

V. arboreum is a perennial shrub/tree of the Ericaceae family that is native to North America.[1]

Distribution

V. arboreum is found throughout the southeastern United States, as far west as Texas and as far north as Illinois.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

Common habitats for V. arboreum include rocky or sandy woodlands, bluffs, and cliffs.[8] Specimens have been collected from longleaf wiregrass sand ridge, broadleaf tree stand, high hammock, upland woodland, live oak hammock, mixed hardwood forest, and in beech magnolia woods.[9]

V. arboreum can grow in medium to coarse textured soils.[1]

The species has a medium tolerance to drought and is tolerant of shade.[1]

V. arboreum reduced its occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in South Carolina's longleaf communities.[10] It has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished pinelands that were disturbed by agriculture, making it a possible indicator species for remnant woodlands.[11] It became absent in response to military training in west Georgia pinelands.[12] This species does not respond to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in north Florida flatwoods forests.[13]

Vaccinium arboreum is frequent and abundant in the North Florida Longleaf Woodlands and Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[14]

Phenology

V. arboreum has been observed to flower January through May and October with peak inflorescence in April.[15]

Fruit begins to develop in summer and lasts to fall.[1]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates.[16]

Fire ecology

V. arboreum has a medium tolerance of fire,[1] but populations have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[17][18][19]

Given V. arboreum is usually maintained by fire, when the habitat is fire suppressed the species will grow to maturity and taller than in fire maintained regions.[8][20]

Pollination

V. arboreum has been observed to host pollinators such as Colletes thoracicus (family Colletidae) and Osmia inspergens (family Megachilidae).[21]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Vaccinium arboreum produces a berry that can be eaten raw or cooked into goods such as jellies or pies.[22]

Medicinally, the bark and leaves can treat sore throat and diarrhea, and the fruit can be used to make a tea for treating dysentery.[23]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 USDA Plant Database

- ↑ Behm, A. L., et al. (2004). "Flammability of native understory species in pine flatwood and hardwood hammock ecosystems and implications for the wildland-urban interface." International Journal of Wildland Fire 13: 355-365.

- ↑ Blair, R. M. (1971). "Forage production after hardwood control in a southern pine-hardwood stand." Forest Science 17(3): 279-284.

- ↑ Bowman, J. L., et al. (1999). Effects of red-cockaded woodpecker management on vegetative composition and structure and subsequent impacts on game species. Proceedings of the Fifty-third Annual Conference, Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. A. G. Wong, P. Doerr, D. Woodward, P. Mazik and R. Lequire. Greensboro, NC, Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies: 220-234.

- ↑ Lay, D. W. (1956). "Effects of prescribed burning on forage and mast production in southern pine forests." Journal of Forestry 29(9): 582-584.

- ↑ Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draf of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draf of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: Florida (Okaloosa, Leon, De Soto, Suwannee, Gadsden, Leon, Wakulla, Taylor, Clay, Hillborough, Levy, Hernando, Citrus, Alachua, Volusia, Walton, Marion, Hamilton, Escambia, Lafayette, Sarasota, Jackson, Holmes, Baker) Georgia (Thomas, Grady) States and counties:

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 29 MAY 2018

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Rodgers, H. L. and L. Provencher (1999). "Analysis of Longleaf Pine Sandhill Vegetation in Northwest Florida." Castanea 64(2): 138-162.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- ↑ Hardin, J.W., Arena, J.M. 1969. Human Poisoning from Native and Cultivated Plants. Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina.

- ↑ Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.