Difference between revisions of "Sorghastrum nutans"

(→Seed dispersal) |

HaleighJoM (talk | contribs) (→Pollination) |

||

| (13 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ||

| − | It is one of the dominant grasses of tall-grass prairies but can be found in xeric and mesic woodlands and forests, along powerline right-of-ways and roadbanks, and in open habitats and forested landscapes.<ref name="Weakley 2015"/> In clayhill longleaf woodlands, ''S. nutans'' occurred in 71% of plots with a mean cover of 2.01 m<sup>2</sup>.<ref name="Carr et al 2010">Carr SC, Robertson KM, Peet RK (2010) A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75(2)153-189.</ref> ''S. nutans'' | + | ''S. nutans'' has been found in Longleaf pine forests, shallow fresh water pools, pine-oak-hickory woods, and turkey oak sand ridges.<ref name="FSU"/> It is also found in disturbed areas including under powerlines, roadsides, disturbed sandhill communities, former pine plantations, burned pineland, and along hiking trails.<ref name="FSU"> Florida State University Herbarium Database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, A. F. Clewell, J. P. Gillespie, R.K. Godfrey, Brenda Herring, Don Herring, and R. Kral. States and counties: Florida: Columbia, Leon, and Wakulla. Georgia: Thomas.</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | It is one of the dominant grasses of tall-grass prairies but can be found in xeric and mesic woodlands and forests, along powerline right-of-ways and roadbanks, and in open habitats and forested landscapes.<ref name="Weakley 2015"/> In clayhill longleaf woodlands, ''S. nutans'' occurred in 71% of plots with a mean cover of 2.01 m<sup>2</sup>.<ref name="Carr et al 2010">Carr SC, Robertson KM, Peet RK (2010) A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75(2)153-189.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''S. nutans'' has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished coastal plain habitat that was disturbed by agriculture in South Carolina, making it a possible indicator species for remnant woodlands.<ref>Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.</ref> ''S. nutans'' also decreased its occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in southwest Georgia.<ref>Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Associated species: ''Heteropogon melanocarpus, Crotalaria spectabilis, Seymeria pectinata'', and ''Tridens flavus''.<ref name="FSU"/> | ||

''Sorghastrum nutans'' is an indicator species for the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).<ref>Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.</ref> | ''Sorghastrum nutans'' is an indicator species for the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).<ref>Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.</ref> | ||

| Line 44: | Line 50: | ||

===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ||

| + | Populations of ''Sorghastrum nutans'' have been known to persist through repeated annual burning.<ref>Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.</ref><ref>Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

Relative frequency in a non-burned Florida site (NB66) was 45 in 1966 and 75 in 2013, suggesting ''S. nutans'' is not fire dependent and is at least moderately shade tolerant.<ref name="Clewell 2014">Clewell AF (2014) Forest development 44 years after fire exclusion in formerly annually burned oldfield pine woodland, Florida. Castanea 79(3):147-167.</ref> However, another study in Kansas showed coverage of unburned areas at 6.3%, while those burned at 4 year intervals and annually had coverage of 16.5 and 42.2%, respectively.<ref name="Abrams 1988">Abrams MD (1988) Effects of burning regime on buried seed banks and canopy coverage in a Kansas tallgrass prairie. The Southwestern Naturalist 33(1):65-70.</ref> Still other studies in an Illinois and Wisconsin prairies did not see any effect of fire on the reproductive tillering, cover, or incidence of ''S. nutans''.<ref name="Copeland et al 2002">Copeland TE, Sluis W, Howe HF (2002) Fire season dominance in an Illinois tallgrass prairie restoration. Restoration Ecology 10(2)315-323.</ref><ref name="Howe 1994">Howe HF (1994) Response of early- | Relative frequency in a non-burned Florida site (NB66) was 45 in 1966 and 75 in 2013, suggesting ''S. nutans'' is not fire dependent and is at least moderately shade tolerant.<ref name="Clewell 2014">Clewell AF (2014) Forest development 44 years after fire exclusion in formerly annually burned oldfield pine woodland, Florida. Castanea 79(3):147-167.</ref> However, another study in Kansas showed coverage of unburned areas at 6.3%, while those burned at 4 year intervals and annually had coverage of 16.5 and 42.2%, respectively.<ref name="Abrams 1988">Abrams MD (1988) Effects of burning regime on buried seed banks and canopy coverage in a Kansas tallgrass prairie. The Southwestern Naturalist 33(1):65-70.</ref> Still other studies in an Illinois and Wisconsin prairies did not see any effect of fire on the reproductive tillering, cover, or incidence of ''S. nutans''.<ref name="Copeland et al 2002">Copeland TE, Sluis W, Howe HF (2002) Fire season dominance in an Illinois tallgrass prairie restoration. Restoration Ecology 10(2)315-323.</ref><ref name="Howe 1994">Howe HF (1994) Response of early- | ||

and late-flowering plants to fire season in experimental prairies. Ecological Applications 4(1):121-133.</ref> | and late-flowering plants to fire season in experimental prairies. Ecological Applications 4(1):121-133.</ref> | ||

===Pollination=== | ===Pollination=== | ||

| − | Individuals of ''S. nutans'' are wind pollinated.<ref name="McKone et al 1998">McKone MJ, Lund CP, O'Brien JM (1998) Reproductive biology of two dominant prairie grasses (''Andropogon gerardii'' and ''Sorghastrum nutans'', Poaceae): Male-biased sex allocation in wind-pollinated plants? American Journal of Botany 85(6):776-783.</ref>Each inflorescence typically releases pollen from 0600 to 1000 for 8 days.<ref name="Jones & Newell 1946">Jones MD, Newell LC (1946) Pollination cycles and pollen dispersal in relation to grass improvement. University of Nebraska College of Agriculture, Agricultural Experiment Station, Research Bulletin 148.</ref> | + | Individuals of ''S. nutans'' are wind pollinated.<ref name="McKone et al 1998">McKone MJ, Lund CP, O'Brien JM (1998) Reproductive biology of two dominant prairie grasses (''Andropogon gerardii'' and ''Sorghastrum nutans'', Poaceae): Male-biased sex allocation in wind-pollinated plants? American Journal of Botany 85(6):776-783.</ref>Each inflorescence typically releases pollen from 0600 to 1000 for 8 days.<ref name="Jones & Newell 1946">Jones MD, Newell LC (1946) Pollination cycles and pollen dispersal in relation to grass improvement. University of Nebraska College of Agriculture, Agricultural Experiment Station, Research Bulletin 148.</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | ===Herbivory and toxicology=== <!--Common herbivores, granivory, insect hosting, poisonous chemicals, allelopathy, etc--> | ||

| + | This species provides nesting material and structure for native bees to build their nests. Caterpillars, including those of the pepper and salt skipper (''Amblyscirtes hegon'') use it for food.<ref name="Ladybird"/> While this species poses little risk for livestock once mature, the young shoots of this plant contain high levels of cyanide and should be avoided.<ref> Burrows, G.E., Tyrl, R.J. 2001. Toxic Plants of North America. Iowa State Press.</ref> Additionally, the plant cannot withstand heavy grazing from cattle.<ref name= "Forestland Grazing">Byrd, Nathan A. (1980). "Forestland Grazing: A Guide For Service Foresters In The South." U.S. Department of Agriculture.</ref> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<!--==Diseases and parasites==--> | <!--==Diseases and parasites==--> | ||

| − | ==Conservation and | + | ==Conservation, cultivation, and restoration== |

| + | Seeds collected in the fall can be propagated by sowing unstratified seeds in the fall or stratified seeds in the spring. Seeds require dry stratification.<ref name="Ladybird"/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Cultural use== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Photo Gallery== | ==Photo Gallery== | ||

Latest revision as of 17:53, 15 July 2022

| Sorghastrum nutans | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John Hilty hosted at IllinoisWildflowers.info | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida - Moncots |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Genus: | Sorghastrum |

| Species: | S. nutans |

| Binomial name | |

| Sorghastrum nutans (L.) Nash | |

| |

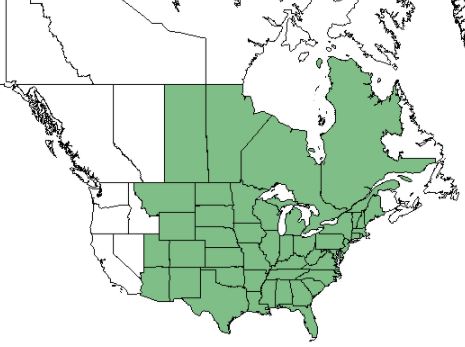

| Natural range of Sorghastrum nutans from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common Name(s): yellow indiangrass;[1] indiangrass[2]

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonym(s): Andropogon nutans[2]; S. avenaceum

Description

Sorghastrum nutans is a monoecious perennial graminoid.[2] It is a bunching sod-forming grass with broad blue-green blades and soft plume-like golden-brown seed heads. This species can reach heights of 3-8 ft (0.91-2.44 m).[3] Its shoot forms a single terminal inflorescence. Dried seeds are between 0.07-1.25 mg, averaging 0.47 mg.[4]

Distribution

This species can be found in 42 of the 48 lower United States, from Arizona, northward through Utah, Wyoming, and Montana, and all states eastward. It also occurs in parts of Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan provinces of Canada and in Mexico.[1][2]

Ecology

Habitat

S. nutans has been found in Longleaf pine forests, shallow fresh water pools, pine-oak-hickory woods, and turkey oak sand ridges.[5] It is also found in disturbed areas including under powerlines, roadsides, disturbed sandhill communities, former pine plantations, burned pineland, and along hiking trails.[5]

It is one of the dominant grasses of tall-grass prairies but can be found in xeric and mesic woodlands and forests, along powerline right-of-ways and roadbanks, and in open habitats and forested landscapes.[1] In clayhill longleaf woodlands, S. nutans occurred in 71% of plots with a mean cover of 2.01 m2.[6]

S. nutans has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished coastal plain habitat that was disturbed by agriculture in South Carolina, making it a possible indicator species for remnant woodlands.[7] S. nutans also decreased its occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in southwest Georgia.[8]

Associated species: Heteropogon melanocarpus, Crotalaria spectabilis, Seymeria pectinata, and Tridens flavus.[5]

Sorghastrum nutans is an indicator species for the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[9]

Phenology

S. nutans has been observed to flower from late August through October[1] as well as November.[10]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity.[11] S. nutans primarily propagates via vegetative propagation and yields few viable seeds during drought years.[12]

Seed bank and germination

Although S. nutans represented 6-42% of plant cover in research plots ranging from unburned to burned in the Konza Prairie, Kansas, no viable seeds of the species were found in the seedbank.[12]

Fire ecology

Populations of Sorghastrum nutans have been known to persist through repeated annual burning.[13][14]

Relative frequency in a non-burned Florida site (NB66) was 45 in 1966 and 75 in 2013, suggesting S. nutans is not fire dependent and is at least moderately shade tolerant.[15] However, another study in Kansas showed coverage of unburned areas at 6.3%, while those burned at 4 year intervals and annually had coverage of 16.5 and 42.2%, respectively.[12] Still other studies in an Illinois and Wisconsin prairies did not see any effect of fire on the reproductive tillering, cover, or incidence of S. nutans.[16][17]

Pollination

Individuals of S. nutans are wind pollinated.[4]Each inflorescence typically releases pollen from 0600 to 1000 for 8 days.[18]

Herbivory and toxicology

This species provides nesting material and structure for native bees to build their nests. Caterpillars, including those of the pepper and salt skipper (Amblyscirtes hegon) use it for food.[3] While this species poses little risk for livestock once mature, the young shoots of this plant contain high levels of cyanide and should be avoided.[19] Additionally, the plant cannot withstand heavy grazing from cattle.[20]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Seeds collected in the fall can be propagated by sowing unstratified seeds in the fall or stratified seeds in the spring. Seeds require dry stratification.[3]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Weakley AS (2015) Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 USDA NRCS (2016) The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 17 January 2018). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Plant database: Sorghastrum nutans. (17 January 2018) Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. URL: https://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=SONU2

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 McKone MJ, Lund CP, O'Brien JM (1998) Reproductive biology of two dominant prairie grasses (Andropogon gerardii and Sorghastrum nutans, Poaceae): Male-biased sex allocation in wind-pollinated plants? American Journal of Botany 85(6):776-783.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Florida State University Herbarium Database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, A. F. Clewell, J. P. Gillespie, R.K. Godfrey, Brenda Herring, Don Herring, and R. Kral. States and counties: Florida: Columbia, Leon, and Wakulla. Georgia: Thomas.

- ↑ Carr SC, Robertson KM, Peet RK (2010) A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75(2)153-189.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 17 JAN 2018

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Abrams MD (1988) Effects of burning regime on buried seed banks and canopy coverage in a Kansas tallgrass prairie. The Southwestern Naturalist 33(1):65-70.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Clewell AF (2014) Forest development 44 years after fire exclusion in formerly annually burned oldfield pine woodland, Florida. Castanea 79(3):147-167.

- ↑ Copeland TE, Sluis W, Howe HF (2002) Fire season dominance in an Illinois tallgrass prairie restoration. Restoration Ecology 10(2)315-323.

- ↑ Howe HF (1994) Response of early- and late-flowering plants to fire season in experimental prairies. Ecological Applications 4(1):121-133.

- ↑ Jones MD, Newell LC (1946) Pollination cycles and pollen dispersal in relation to grass improvement. University of Nebraska College of Agriculture, Agricultural Experiment Station, Research Bulletin 148.

- ↑ Burrows, G.E., Tyrl, R.J. 2001. Toxic Plants of North America. Iowa State Press.

- ↑ Byrd, Nathan A. (1980). "Forestland Grazing: A Guide For Service Foresters In The South." U.S. Department of Agriculture.