Difference between revisions of "Schizachyrium scoparium"

(→Distribution) |

HaleighJoM (talk | contribs) (→Ecology) |

||

| (11 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

==Description== | ==Description== | ||

<!-- Basic life history facts such as annual/perrenial, monoecious/dioecious, root morphology, seed type, etc. --> | <!-- Basic life history facts such as annual/perrenial, monoecious/dioecious, root morphology, seed type, etc. --> | ||

| − | ''S. scoparium'' is a perennial graminoid of the ''Poaceae'' family native to North America and Canada and introduced to Hawaii.<ref name= "USDA Plant Database"> USDA Plant Database [https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=SCSC https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=SCSC] </ref> | + | ''S. scoparium'' is a perennial graminoid of the ''Poaceae'' family native to North America and Canada and introduced to Hawaii.<ref name= "USDA Plant Database"> USDA Plant Database [https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=SCSC https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=SCSC] </ref> It is a primary groundcover species in longleaf pine forest. Bluestem grows both solitary and in clumps and reaches heights up to 4.5 feet tall with 10 inch long, narrow leaf blades. The plant possesses flowering spikes that grow on evenly distributed stalks up the stem. These flowers bloom in the fall and seeds disperse in November. There are a couple noted subspecies var. ''divergens'' (pinehill bluestem) and var. ''stoloniferum'' (creeping bluestem), the latter is only found in central longleaf pine range.<ref>Denhof, Carol. 2012. Plant Spotlight Schizachyrium Scoparium (Michx.) Nash var. scoparium Little Bluestem. The Longleaf Leader - Longleaf Reflections: Looking Back, Taking Stock, Moving Forward. Vol. XI. Iss. 3. Page 6</ref><ref>Miller, J.H. and K.V. Miller. Forest Plants of the Southeast and their Wildlife Uses. The University of Georgia Press, Atehns, GA. 454pp.</ref><ref>Sorries, B.A. 2011. A Field Guide to Wildflowers of the Sandhills Region. The University of North Carolina Press. Chapel Hill, NC. 378pp.</ref><ref>USDA, NRCS. 2018 The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 29 September 2011). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.</ref> |

==Distribution== | ==Distribution== | ||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ||

| − | ''S. scoparium'' proliferates in various open habitats, in a wide range of moist to dry habitats, fall-line sandhills in the inner Coastal Plain, perhaps in other dry habitats. <ref name= "Weakley 2015"> Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium. </ref> It also occurs often in relic ''P. palustris''/wiregrass communities. <ref name= "Andreu 2009"> Andreu, M. G., et al. (2009). "Can managers bank on seed banks when restoring Pinus taeda L. plantations in Southwest Georgia?" Restoration Ecology 17: 586-596. </ref> Specimens have been collected from wet pine flatwoods, palmetto slash pine woodland, oak-palmetto woodland, blaffs along river, treeless chalk glade, wet road ditch, cypress swamp, dry glade, palm hammock, sand-pine oak woodland, slashpine savanna, longleaf pine sand ridge, pine flatwoods, longleaf pine wiregrass savanna, upland old field, pond pine flatwoods, and open river banks.<ref name = "FSU herbarium"> URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: R.K. Godfrey, Angus Gholson, Cecil Slaughter, Loran C. Anderson, Mark A> Garland, Marc Minno, Wilson Baker, Ann F. Johnson, R. Komarek, R. Kral, Richard S. Mitchell, R. E. Perdue, A.F. Clewell, Robert Blaisdell, Robert Lazor, Ginny Vail, Sidney McDaniel. States and counties: Georgia (Grady, Thomas, Baker) Alabama (Crenshaw) Louisiana (Winn) Florida (Grady, Okaloosa, Indian River, Franklin, Gadsden, Clay, Wakulla, Jackson, Volusia, Flagler, Leon, Walton, Bay, Escambia, Liberty, Columbia, Osceola, Marion, Taylor, Madison, Levy, Dixie, Baker, Calhoun, Okaloosa, Santa Rosa, Nassau) </ref> It is considered to be a species that is indicative of non-agricultural history on frequently burned longleaf pine habitat.<ref name= "Hahn"/> ''S. scoparium'' | + | ''S. scoparium'' proliferates in various open habitats, in a wide range of moist to dry habitats, fall-line sandhills in the inner Coastal Plain, perhaps in other dry habitats. <ref name= "Weakley 2015"> Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium. </ref> It also occurs often in relic ''P. palustris''/wiregrass communities. <ref name= "Andreu 2009"> Andreu, M. G., et al. (2009). "Can managers bank on seed banks when restoring Pinus taeda L. plantations in Southwest Georgia?" Restoration Ecology 17: 586-596. </ref> Specimens have been collected from wet pine flatwoods, palmetto slash pine woodland, oak-palmetto woodland, blaffs along river, treeless chalk glade, wet road ditch, cypress swamp, dry glade, palm hammock, sand-pine oak woodland, slashpine savanna, longleaf pine sand ridge, pine flatwoods, longleaf pine wiregrass savanna, upland old field, pond pine flatwoods, and open river banks.<ref name = "FSU herbarium"> URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: R.K. Godfrey, Angus Gholson, Cecil Slaughter, Loran C. Anderson, Mark A> Garland, Marc Minno, Wilson Baker, Ann F. Johnson, R. Komarek, R. Kral, Richard S. Mitchell, R. E. Perdue, A.F. Clewell, Robert Blaisdell, Robert Lazor, Ginny Vail, Sidney McDaniel. States and counties: Georgia (Grady, Thomas, Baker) Alabama (Crenshaw) Louisiana (Winn) Florida (Grady, Okaloosa, Indian River, Franklin, Gadsden, Clay, Wakulla, Jackson, Volusia, Flagler, Leon, Walton, Bay, Escambia, Liberty, Columbia, Osceola, Marion, Taylor, Madison, Levy, Dixie, Baker, Calhoun, Okaloosa, Santa Rosa, Nassau) </ref> It is considered to be a species that is indicative of non-agricultural history on frequently burned longleaf pine habitat.<ref name= "Hahn"/> |

| + | |||

| + | ''S. scoparium'' became absent or decreased its occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in southwest Georgia. It has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished pine forests that were disturbed by agricultural practices.<ref name=hedman>Hedman, C.W., S.L. Grace, and S.E. King. (2000). Vegetation composition and structure of southern coastal plain pine forests: an ecological comparison. Forest Ecology and Management 134:233-247.</ref> | ||

''Schizachyrium scoparium'' var. ''stoloniferum'' is frequent and abundant in the Peninsula Xeric Sandhills, Panhandle Xeric Sandhills, North Florida Subxeric Sandhills, Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands, Panhandle Silty Longleaf Woodlands, and Upper Panhandle Savannas community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).<ref>Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.</ref> | ''Schizachyrium scoparium'' var. ''stoloniferum'' is frequent and abundant in the Peninsula Xeric Sandhills, Panhandle Xeric Sandhills, North Florida Subxeric Sandhills, Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands, Panhandle Silty Longleaf Woodlands, and Upper Panhandle Savannas community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).<ref>Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.</ref> | ||

| Line 42: | Line 44: | ||

===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ||

| − | ''S. scoparium'' is highly fire tolerant, resprouting quickly following fire, and is the dominant grass species in some fire-dependent communities (e.g., western upland longleaf pine forest).<ref>Smith, L. 2009. The natural communities of Louisiana. Louisiana Natural Heritage Program, Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, 46 pp.</ref> A study found overall herbivory to decrease with higher fire return interval regiments.<ref name= "Hahn"/> | + | ''S. scoparium'' is highly fire tolerant, resprouting quickly following fire, and is the dominant grass species in some fire-dependent communities (e.g., western upland longleaf pine forest).<ref>Smith, L. 2009. The natural communities of Louisiana. Louisiana Natural Heritage Program, Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, 46 pp.</ref> Populations have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.<ref>Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.</ref><ref>Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.</ref> A study found overall herbivory to decrease with higher fire return interval regiments.<ref name= "Hahn"/> |

<!--===Pollination===--> | <!--===Pollination===--> | ||

| − | === | + | ===Herbivory and toxicology===<!--Common herbivores, granivory, insect hosting, poisonous chemicals, allelopathy, etc--> |

| − | ''S. scoparium'' has medium palatability for browsing animals and high palatability for grazing animals. <ref name= "USDA Plant Database"/> It is sometimes foraged by common grasshoppers in the subfamilies Melanoplinae and Cyrtacanthacridinae, which are known as mixed feeders.<ref name= "Hahn">Hahn, P. C. and J. L. Orrock (2015). "Land-use legacies and present fire regimes interact to mediate herbivory by altering the neighboring plant community." Oikos 124: 497-506.</ref> | + | ''S. scoparium'' has been observed to host bugs such as ''Scolops sulcipes'' (family Dictyopharidae).<ref>Discoverlife.org [https://www.discoverlife.org/20/q?search=Bidens+albaDiscoverlife.org|Discoverlife.org]</ref> ''S. scoparium'' has medium palatability for browsing animals and high palatability for grazing animals.<ref name= "USDA Plant Database"/> This species provides forage for cattle that can withstand heavier grazing.<ref name= "Forestland Grazing">Byrd, Nathan A. (1980). "Forestland Grazing: A Guide For Service Foresters In The South." U.S. Department of Agriculture.</ref> It is sometimes foraged by common grasshoppers in the subfamilies Melanoplinae and Cyrtacanthacridinae, which are known as mixed feeders.<ref name= "Hahn">Hahn, P. C. and J. L. Orrock (2015). "Land-use legacies and present fire regimes interact to mediate herbivory by altering the neighboring plant community." Oikos 124: 497-506.</ref> The plant also makes excellent nesting cover for the bobwhite quail and provides seeds for forage.<ref>Denhof, Carol. 2012. Plant Spotlight Schizachyrium Scoparium (Michx.) Nash var. scoparium Little Bluestem. The Longleaf Leader - Longleaf Reflections: Looking Back, Taking Stock, Moving Forward. Vol. XI. Iss. 3. Page 6</ref><ref>Miller, J.H. and K.V. Miller. Forest Plants of the Southeast and their Wildlife Uses. The University of Georgia Press, Atehns, GA. 454pp.</ref><ref>Sorries, B.A. 2011. A Field Guide to Wildflowers of the Sandhills Region. The University of North Carolina Press. Chapel Hill, NC. 378pp.</ref><ref>USDA, NRCS. 2018 The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 29 September 2011). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.</ref> |

<!--==Diseases and parasites==--> | <!--==Diseases and parasites==--> | ||

| − | ==Conservation and | + | ==Conservation, cultivation, and restoration== |

| + | ''S. scoparium'' should avoid soil disturbance by agriculture to conserve its presence in pine communities.<ref name=hedman/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Cultural use== | ||

| − | |||

==Photo Gallery== | ==Photo Gallery== | ||

<gallery widths=180px> | <gallery widths=180px> | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

==References and notes== | ==References and notes== | ||

Latest revision as of 16:00, 15 July 2022

Common name: pinehill bluestem[1], common little bluestem[1], creeping little bluestem[1], little bluestem[2]

| Schizachyrium scoparium | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John Hilty hosted at IllinoisWildflowers.info | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida - Moncots |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Genus: | Schizachyrium |

| Species: | S. scoparium |

| Binomial name | |

| Schizachyrium scoparium (Michx.) Nash | |

| |

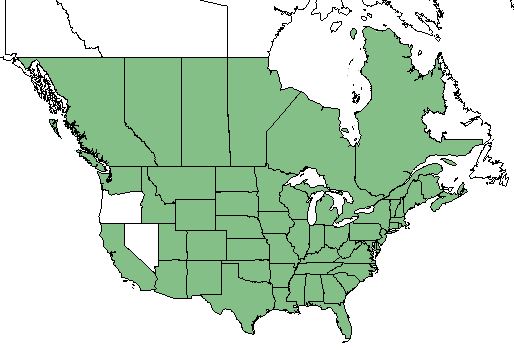

| Natural range of Schizachyrium scoparium from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: (for var. divergens) Andropogon scoparius Michaux var. divergens Hackel; Andropogon divergens; (for var. scoparium) S. scoparium; S. scoparium ssp. scoparium; (for var. stoloniferum) S. stoloniferum Nash; Andropogon stolonifer (Nash) A.S. Hitchcock

Varieties: Schizachyrium scoparium (Michaux) Nash var. divergens (Hackel) Gould; Schizachyrium scoparium (Michaux) Nash var. scoparium; Schizachyrium scoparium (Michaux) Nash var. stoloniferum (Nash) J. Wipff

Description

S. scoparium is a perennial graminoid of the Poaceae family native to North America and Canada and introduced to Hawaii.[2] It is a primary groundcover species in longleaf pine forest. Bluestem grows both solitary and in clumps and reaches heights up to 4.5 feet tall with 10 inch long, narrow leaf blades. The plant possesses flowering spikes that grow on evenly distributed stalks up the stem. These flowers bloom in the fall and seeds disperse in November. There are a couple noted subspecies var. divergens (pinehill bluestem) and var. stoloniferum (creeping bluestem), the latter is only found in central longleaf pine range.[3][4][5][6]

Distribution

S. scoparium is found: everywhere in the United States excluding Oregon and Nevada; every region in Canada; every island in Hawaii.[2]

Ecology

Habitat

S. scoparium proliferates in various open habitats, in a wide range of moist to dry habitats, fall-line sandhills in the inner Coastal Plain, perhaps in other dry habitats. [1] It also occurs often in relic P. palustris/wiregrass communities. [7] Specimens have been collected from wet pine flatwoods, palmetto slash pine woodland, oak-palmetto woodland, blaffs along river, treeless chalk glade, wet road ditch, cypress swamp, dry glade, palm hammock, sand-pine oak woodland, slashpine savanna, longleaf pine sand ridge, pine flatwoods, longleaf pine wiregrass savanna, upland old field, pond pine flatwoods, and open river banks.[8] It is considered to be a species that is indicative of non-agricultural history on frequently burned longleaf pine habitat.[9]

S. scoparium became absent or decreased its occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in southwest Georgia. It has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished pine forests that were disturbed by agricultural practices.[10]

Schizachyrium scoparium var. stoloniferum is frequent and abundant in the Peninsula Xeric Sandhills, Panhandle Xeric Sandhills, North Florida Subxeric Sandhills, Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands, Panhandle Silty Longleaf Woodlands, and Upper Panhandle Savannas community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[11]

Phenology

S. scoparium has been observed to flower in November. [12]

Fire ecology

S. scoparium is highly fire tolerant, resprouting quickly following fire, and is the dominant grass species in some fire-dependent communities (e.g., western upland longleaf pine forest).[13] Populations have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[14][15] A study found overall herbivory to decrease with higher fire return interval regiments.[9]

Herbivory and toxicology

S. scoparium has been observed to host bugs such as Scolops sulcipes (family Dictyopharidae).[16] S. scoparium has medium palatability for browsing animals and high palatability for grazing animals.[2] This species provides forage for cattle that can withstand heavier grazing.[17] It is sometimes foraged by common grasshoppers in the subfamilies Melanoplinae and Cyrtacanthacridinae, which are known as mixed feeders.[9] The plant also makes excellent nesting cover for the bobwhite quail and provides seeds for forage.[18][19][20][21]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

S. scoparium should avoid soil disturbance by agriculture to conserve its presence in pine communities.[10]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 USDA Plant Database https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=SCSC

- ↑ Denhof, Carol. 2012. Plant Spotlight Schizachyrium Scoparium (Michx.) Nash var. scoparium Little Bluestem. The Longleaf Leader - Longleaf Reflections: Looking Back, Taking Stock, Moving Forward. Vol. XI. Iss. 3. Page 6

- ↑ Miller, J.H. and K.V. Miller. Forest Plants of the Southeast and their Wildlife Uses. The University of Georgia Press, Atehns, GA. 454pp.

- ↑ Sorries, B.A. 2011. A Field Guide to Wildflowers of the Sandhills Region. The University of North Carolina Press. Chapel Hill, NC. 378pp.

- ↑ USDA, NRCS. 2018 The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 29 September 2011). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ Andreu, M. G., et al. (2009). "Can managers bank on seed banks when restoring Pinus taeda L. plantations in Southwest Georgia?" Restoration Ecology 17: 586-596.

- ↑ URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: R.K. Godfrey, Angus Gholson, Cecil Slaughter, Loran C. Anderson, Mark A> Garland, Marc Minno, Wilson Baker, Ann F. Johnson, R. Komarek, R. Kral, Richard S. Mitchell, R. E. Perdue, A.F. Clewell, Robert Blaisdell, Robert Lazor, Ginny Vail, Sidney McDaniel. States and counties: Georgia (Grady, Thomas, Baker) Alabama (Crenshaw) Louisiana (Winn) Florida (Grady, Okaloosa, Indian River, Franklin, Gadsden, Clay, Wakulla, Jackson, Volusia, Flagler, Leon, Walton, Bay, Escambia, Liberty, Columbia, Osceola, Marion, Taylor, Madison, Levy, Dixie, Baker, Calhoun, Okaloosa, Santa Rosa, Nassau)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Hahn, P. C. and J. L. Orrock (2015). "Land-use legacies and present fire regimes interact to mediate herbivory by altering the neighboring plant community." Oikos 124: 497-506.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Hedman, C.W., S.L. Grace, and S.E. King. (2000). Vegetation composition and structure of southern coastal plain pine forests: an ecological comparison. Forest Ecology and Management 134:233-247.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 29 MAY 2018

- ↑ Smith, L. 2009. The natural communities of Louisiana. Louisiana Natural Heritage Program, Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, 46 pp.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- ↑ Byrd, Nathan A. (1980). "Forestland Grazing: A Guide For Service Foresters In The South." U.S. Department of Agriculture.

- ↑ Denhof, Carol. 2012. Plant Spotlight Schizachyrium Scoparium (Michx.) Nash var. scoparium Little Bluestem. The Longleaf Leader - Longleaf Reflections: Looking Back, Taking Stock, Moving Forward. Vol. XI. Iss. 3. Page 6

- ↑ Miller, J.H. and K.V. Miller. Forest Plants of the Southeast and their Wildlife Uses. The University of Georgia Press, Atehns, GA. 454pp.

- ↑ Sorries, B.A. 2011. A Field Guide to Wildflowers of the Sandhills Region. The University of North Carolina Press. Chapel Hill, NC. 378pp.

- ↑ USDA, NRCS. 2018 The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 29 September 2011). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.